Recovery and Rehabilitation#

Some Frivolous Thoughts on a Very Serious Subject#

By now you know that surgeons can’t repair spinal cords and that recovery is exceedingly rare. There have been isolated cases of hysterical paralysis cured through hypnosis, but no cases of traumatic paralysis being cured by anything. Your best shot is having an incomplete lesion, in which case nature sometimes squeaks through, a little at a time, and there is then some return of function. Complete functional return is very unlikely. So rehabilitation is the task at hand. Rehabilitation’s job is to take your body as it is and to maximize your capabilities within recognized limitations.

This is a difficult acknowledgment. Rehabilitation seems only second best, which is exactly what it is. To fully accept rehabilitation, for most of us, is to effectively abandon recovery. Rehabilitation can give you strength, re-education, skills and real improvement, but no cure. Many people find this an easy bridge to cross, and a few find it so upsetting that they temporarily want out of the game.

Your body: love it or leave it? The contemplation of suicide, as a singular experience, is pretty common and is not at all the same thing as being suicidal. It’s a valid question, not one to hide or be ashamed of, and it’s a question which should be dealt with very directly. Don’t delay, because suicidal thoughts are crummy companions on lonely nights. Ask yourself whether you want to live or die. Ask out loud if necessary, but get the question out in the open and out of your mind. While you’re at it, ask yourself if you have enough information yet to make an intelligent decision.

Many SCI’s have told me that they once contemplated suicide, usually soon after their accidents. They were all, of course, still alive when I met them. In fact, while provable suicide is not unknown in SCI, it is uncommon. But self-destructive refusal by the individual to take responsibility for his or her own health is quite common. (If you want percentages and numbers, see Roberta Trieschmann’s book, cited in the bibliography.) Somehow, malign neglect seems like a particularly wishy-washy way to make a statement.

And then, suicide has disadvantages that exceed even those of SCI. You’re in a bind, and the only way to proceed is to proceed.

If we can’t get off our asses to do something, then the next best thing is to get on our asses and do something. Screw it; just do it. Get up, get started, get going. You can always kill yourself later. Then, when you’ve picked up some new skills, you’ll know enough about what you can do that your curiosity might be aroused. So give rehabilitation a try, because it’s what you need. And refer to the next chapter to see if you’re in the right place to get it.

Is This the Right Place?#

Large general hospitals, where most people land after any kind of major injury, are magnificently equipped and staffed to handle the acute phases of pretty much any trauma. What they tend to be less good at is the extended specialized care and rehabilitation services required by SCI.

All SCI treatment is not created equal. It varies from excellent to atrocious. Recognizing this fact, the National Rehabilitation Act of 1973 designated 11 Regional Spinal Cord Injury Centers, some of which have satellite units. The number of centers has now grown to 15. If you are in one of these centers, you’re extremely fortunate. If you’re not, and over 85% of new injuries are not, then you need some criteria for judging the quality of the care you are getting. It may be excellent, but you need to know if it’s not.

You need medical and nursing personnel with extensive experience in the management of SCI. Seeing three or four SCI’s a year is not adequate qualification.

You need Whole Body Care. Most hospitals are collections of diverse services which surgerize, repair pressure sores and treat urinary infections, contractures, pulmonary complications and troubled psyches only after these needs have been created by incomplete preventive medical care. A good SCI facility will assign one doctor who specializes in SCI (not neurosurgery) to coordinate the work of the rest of the staff. That is, he will act as an advocate for your whole body, not just your individual parts. He, with your diligent cooperation, is your insurance against preventable complications.

You need the company and counsel of people with injuries similar to yours. Unfortunately, this is your most alienable right. In a large city hospital, you’ll be lucky to find three or four other SCI’s, and you’ll probably only see them going the other direction down a hallway on a gurney. In any SCI Center, there will be dozens of other SCI’s, and you’ll spend most of every day with them. This might sound depressing to you. It’s not. It’s creative and invigorating. In addition, there is a constant flow of old grads returning for occasional reevaluation. The sheer quantity of information, the multitude of coping ideas and solutions and the ease of communication when all present have similar concerns are truly galvanizing. These people are far and away your best advisors and your best access to information.

You need therapists and counselors who are specifically trained in SCI, and the facilities (gym, weights, mats, bars, bracing, adaptive devices, recreation facilities, etc.) for effecting your rehabilitation.

A few general hospitals can provide you with all these things, and well. So can a number of rehabilitation centers outside of designated Regional SCI Centers. See how you feel about the considerations below, then make a decision. Remember that SCI Centers can’t work miracles. They can no more repair spinal cords than any other hospital. They can get you up and moving, and that is the present need.

If you’re expending most of your time and energy fighting recurrent pressure sores or bladder infections, you’re in the wrong place.

If you can’t get frank and specific answers to your questions about emptying your bladder, moving your bowels, or your sexual or occupational expectations, you’re in the wrong place. For that matter, you’re in the wrong place if those questions are difficult to ask.

If all or most of your time is spent in your room, even after the acute phase has passed, or if you are moved only once daily for an hour in a physical therapy cubicle, you’re in the wrong place.

If you have the feeling you’re being hidden, you’re in the wrong place.

If you’re not being taught to become a genuine expert, the expert, on all aspects of your own health, you’re in the wrong place.

Treat yourself right. Give yourself every chance. It behooves you to get to a good rehabilitation facility to be kind to yourself, and it behooves your insurance company or financial aid source to expedite your transfer because better care is cheaper care. That’s because you’ll be out of rehabilitation faster and healthier and better equipped to stay out. Don’t let yourself be victimized by incomplete knowledge of your condition and of your abilities. And most of all, don’t allow yourself to be filed away in a neurological ward or nursing home without examining all the alternatives.

“Keep active, keep trying things, and don’t find the answer. Don’t let someone tell you you’ve found the answer, because if you do, by God, it’s gonna be an institution or it’s gonna be a nursing home or it’s gonna be invalidism in your own house. Because that’s the answer, statistically, that most paraplegics and quadriplegics have and get. Keep doing things, keep making mistakes, and don’t follow all the instructions because you will not find new behavior that way. And if you don’t find new ways of behaving, you aren’t going to find new reinforcements. You’re not gonna get paid off in novel experiences, so your life is gonna become very constricted. I guess what I’m trying to say is that if you find yourself in this kind of constricted life, and you don’t want it, then keep wigglin’, keep movin’, stay alive.”

—George Hohmann

Corners#

Let’s say there exists a corner which you have to turn, and after that you’re home free. Not that you’ll take up pole-vaulting again, but just that your life will settle out into a reasonable and workable thing once you’ve turned the corner. Maybe the corner is the point at which you concern yourself more with the activity and less with the anxiety of living.

Corners need some examination—they’re potentially tricky. Like, is turning the corner just a defeatist acceptance of the unacceptable? An act of faith, which is fine if you’re of the faithful? Is it the decision to live, as opposed to only exist? It might be scary around the corner, then again, maybe there’s a risk of fooling yourself into thinking you’re OK because you want so badly to see around that corner. Perhaps the staff has programmed you with insidious intervention strategies and behavior modification lurks behind every smile of encouragement.

Or perhaps you see something. A goal, a real reward out there that’s realizable and worth working toward. If so, if you have that awareness of a desirable objective and sense that you can influence the odds of achieving it, then you are home free. That’s the corner.

Goals come in two forms. There are take-one-day-at-a-time goals which sustain and amuse us in the absence of passion. Business as usual; busy as hell. And there are the goals we perceive way out there in the future-murk which we will work toward with consuming passion. The identification of realistic goals is the keystone of all rehabilitation.

No goals; no home free corner. No free lunch. An immediate goal might be to find a goal…

But perhaps you feel that, personally, you’re sort of short on goals. Sort of, excuse me, crippled by apathy. Today, tomorrow and forever. That’s understandable, but it leaves you only the past to deal with, and that’s going to get boring.

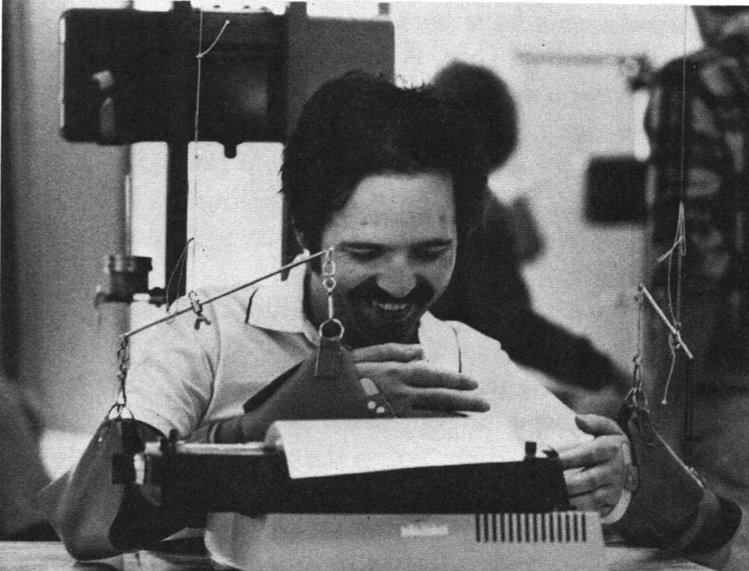

So pick a goal. Manufacture one. Make a phone call. Make the night nurse laugh. Put cranberry juice in your leg bag without drinking it first. Or, what the hell, do a transfer just to please someone. Have a voluntary. Take a therapist to lunch. Pick anything you haven’t been doing but can do, then do it. Little successes feel good and spawn new goals which have real heart to them. Achieved goals have a snowballing effect. And when you become President, remember that you once thought getting dressed or holding a fork was a significant challenge.

And if you still can’t scratch up any enticing goals, it’s probably because you’re not aware yet of the options available to you once you start hustling. Most of the people in this book had the same problem. They can open doors for you. You don’t have to go through the doors, but they do ease the passage if you’re bumping into walls.

Lighting a Fire#

“Better to light one candle than to curse the darkness.”

“Motivation is within each individual. If it can be found, if a person can find it by himself, with assistance, with some counseling, with whatever is necessary, that is going to be the trigger that moves them towards a goal, towards a success and a feeling of satisfaction.”

—Gene Tchida

“Looking back on it now (after 23 years!), I probably was too eager to accept DVR’s answers of me being severely disabled and not becoming independent. But when I look back, I can see that the only way for me to get out of the four walls I was looking at was for me to make the effort. And finally, at long last, I learned this lesson.”

—Bob McGinty

“A healthy skepticism is what you need, because you are unique and the way you recover and the way you will adapt will be totally different from the way anybody else does. And if you allow anyone to define you, you allow them to deprive you of some of those abilities that you might have, that you more than likely do have. It’s just incredible that people let other people define them.”

—John Galland

“If the person is accomplishment-oriented, they will do it their injury be damned. Regardless. If they’re not accomplishment-oriented, their disability will become the reason for not accomplishing.”

—Elmer Bartels

“I think people have to first create in themselves a force or a will to do something different, and then create a little person behind them to push them through it. And it can be done. People can do whatever they want to do. It’s just a matter of focussing your mind on it and going with it.”

—Jim Albert

“I became very motivated and directed. And I think that the two biggest things that contributed to that was that I went right back into what I was doing before, and I didn’t lower my expectations.”

—Nancy Becker Kennedy

“The idea is to expand choices, to give people all the choices they want. Then you’re no longer handicapped.”

—Steve Epstein

“When I think about all the things I can do and can’t do, it seems to me that there’s an awful lot of things left to do.”

—W. Mitchell

More on Rehabilitation…#

Basic rehabilitation is a drag. It teaches you what you learned in the first four years of life—mobility, personal hygiene, avoidance of hazards, muscle development and other pretty unoriginal stuff. The best thing going for it is that not doing it is much worse than doing it.

But that’s just Rehab 101. If you’re in a good place, you can attend a Sexual Attitude Reassessment seminar (sounds ominous, but they show you lots of dirty movies), learn to drive a car (takes 10 minutes if you’ve driven before — instant freedom!), join group sessions on relationships, self-image, self-presentation, or whatever else needs discussion, receive vocational counseling and training, learn about money sources, get in some recreation and maybe get out on the town and mix with some normies. (They’re pretty weird, but you get used to them.) Lots of good information here, and even some good fun. Enter rehabilitation with a full heart.

Remember that the genuine aim of rehabilitation is to achieve your goals. Tell them what you want to accomplish, show them that you’re willing to work, and they’ll literally give you the world. And consider that the various therapists—occupational, physical, speech, GU, sexual and recreational—are specialists and can’t be expected to intuit your overall needs. Make it your responsibility to bring their skills together to achieve your goal.

And what’s your goal? To escape, of course.

The Great Escape#

It’s a little like getting out of jail, except that the staff wants you outside instead of inside. So line up your shots. Acquire the physical skills to be as independent as your injury allows. Acquire the social skills to deal with other people. Acquire an attendant, if you need one, or perhaps a job, a car, an education, a lover or a place to live. Then figure out the realities of paying for these things. Learn all you can about the care and maintenance of your body and mind. And understand fully that once you do escape, your rehabilitation will begin in earnest.

If you’re nervous about the escape, inquire about the equivalent of minimum security lockup. Many SCI centers can provide out-patient apartments which still have access to hospital services. Occupancy is temporary, but can ease the transition.

But don’t hang around any longer than you have to. Institutionalization is addictive. Move on out, because there’s a big world out there, and it’s just as ready for you as you are for it.

Postpartum Blues#

It’s only fair to warn you that many of us have found the first weeks or months after the escape to be the most difficult ones of all. Hard times. While the institution was toilet training you and teaching you mobility, it was also becoming your sheltering mother who loved you in spite of your flaws, real or imagined. That comfortable shelter can be difficult to abandon for the ragged, jagged edges of real life.

The best preparation is simply to know ahead of time that there might be a low spell, and to know that, if it does occur, it will wear itself out. People tend to let themselves be surprised by post-institutional depression, which makes them more vulnerable than they need to be. Better to be forewarned. If it happens, it happens. It will end after awhile. If it doesn’t happen, rejoice but do not gloat. Virtually everyone has some down period after a major injury. And when you’re down, it’s easy to think that all of your days will be this way. Always. They won’t. The blues will depart like a case of the mumps.

And with this caution and this encouragement, and with only occasional interruptions, I give you into the hands of the real and true authors of this book.