Lives VII#

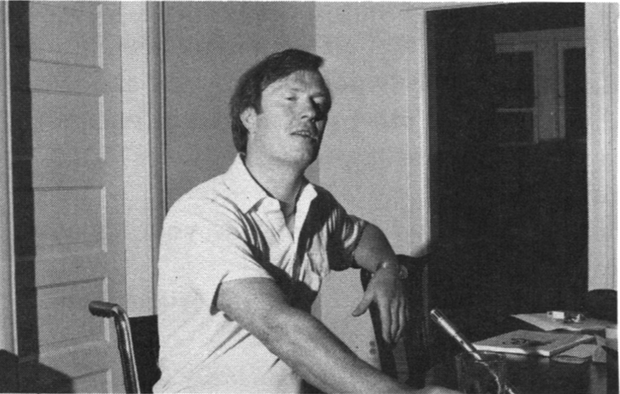

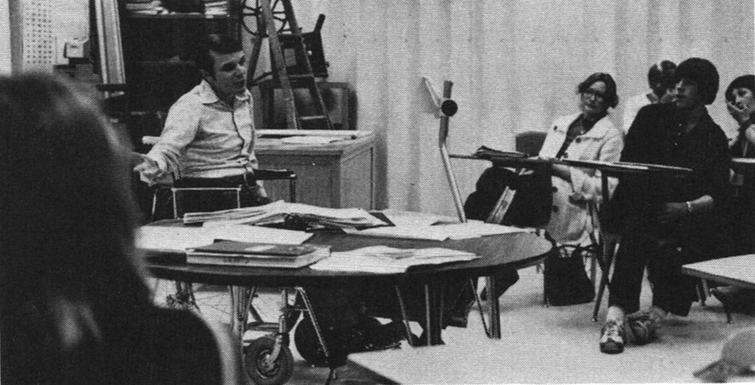

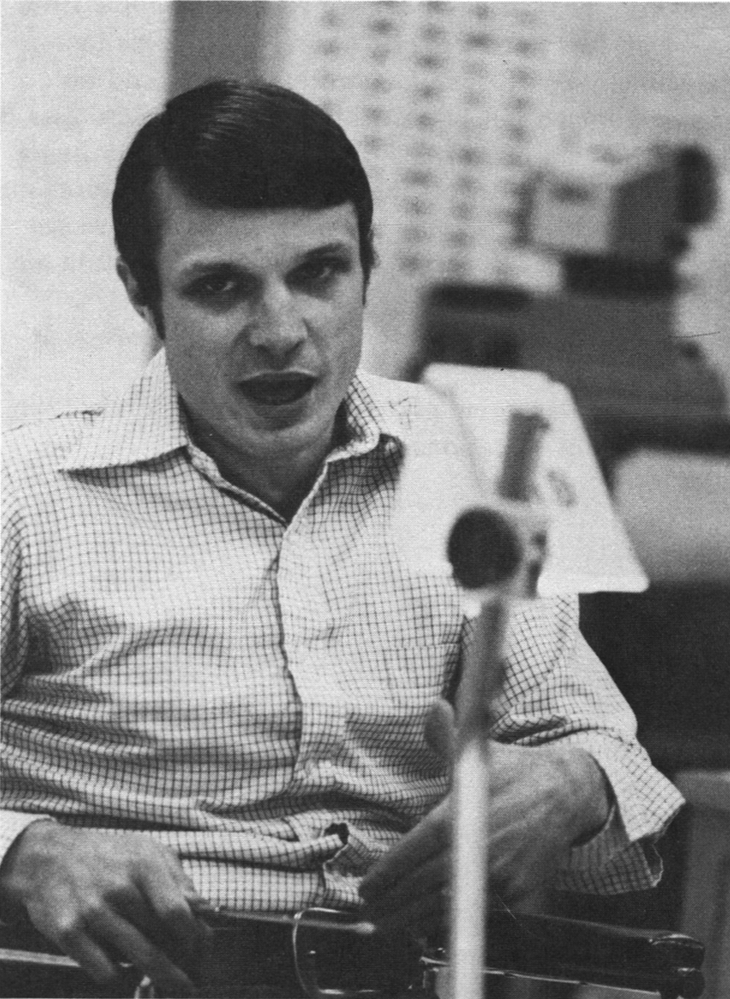

Jim Albert#

We’d agreed to meet Jim for lunch at his house in Livermore, California. He’d eat and we’d bug him.

Jim showed up on time, turning the corner in a shock pink Porsche. I later stood corrected: “That car’s my heart. That was my thirtieth birthday present (from himself to himself) and it had to be that color. It’s called magenta.”

It’s a comfortable house, complete with swimming pool, which Jim shares with his wife of two years. Between munches on a sandwich, Jim tells us about himself.

“Ever since I was a kid, I was fascinated by airplanes. I wanted to become an aeronautical engineer. I wanted to design airplanes. In fact, I did—I had to design an airplane to get out of college and I went to work as an aerodynamicist for Lockheed. But I got into computer simulation doing that. I got turned on by the computer simulation as opposed to the designing of the airplanes. And that’s when I had my accident.”

Jim did it on a motorcycle. “My first and last ride. Yeah, the first time I’d ever seen a motorcycle.” He was 21, a T5,6,7 para, and, after three months of head-to-toe pressure sores at a general hospital and another three months of repair work at a rehabilitation center, he was once again confronted with a career choice.

“So when I went back to college, I had to decide which I like doing most. Do I want to continue playing with airplanes or do I want to start playing with computers? And I decided, well, I wanted to play with airplanes and computers. So I got into automatic computer guidance and control of aircraft and missiles.” Jim does have a taste for expensive toys.

Before his accident, he had a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering from USC. After his accident, he went to school part-time (UCLA, cheaper and more accessible) and worked part-time on his guidance systems.

“When I graduated with a master’s in computer systems engineering, I moved up here. I finally left aircraft when I came to the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory and started into computers on a full-time basis. I’m a principal computer scientist for the Computer Operations Division. Currently, I’m developing a network of intelligent computer terminals. Each terminal is a mini-computer. And now I’m connecting very large CDC 7600 computers to those terminals, making the terminals control teletypes so that the terminals can talk to each other, talk to the main computers and put out graphic displays for the computer operator in real time.”

Personally, I’m delighted that this is what Jim does. I can think of no happier scenario than all those little mini-computers chatting and giggling together like teenaged girls first discovering a party line, while big momma CDC 7600 proudly and patiently looks on. I had brought my usual prejudices with me, one of which was that anyone who worked for the Lawrence Livermore Lab necessarily dealt with blunt instruments of global destruction. Not entirely so. Jim, a man of conscience, likes his work and plans to enroll at Stanford next summer without leaving Livermore. To do this, it helps to be into computers and related communication technology.

“I’m planning on entering Stanford as a PhD candidate in computer design. My company is connected to a closed circuit TV network where you can take Stanford courses at work and effectively be in the classroom because there’s two-way communication in real time. They broadcast the class over TV and you can sit in class and ask questions back and forth over the TV even as the instructor is giving the class at Stanford. You don’t have to go over there except to buy books or use the library. You can get a large portion of the units for a degree right here.”

Has your accident affected your employability? “It hasn’t lessened my employability. Well, yeah, let’s say maybe. Because there was a job where I felt that there was some discrimination going on. But since I have two strikes against me, I couldn’t figure out which one it was. So I said to hell with it and got another job. I’ve never had any trouble holding on to a job. I’m good at what I do and that keeps them giving me raises and paying me.”

Other interests? Friday, he’s going to a wine and cheese party. The party is the Berkeley CIL’s way of introducing area employers to new graduates of their Computer Training Project. Jim started the project.

Saturday, he’s giving a seminar in jujitsu at a junior college in Santa Cruz. As people call him up to do seminars, he does them. He holds a green belt. He’s an official timer for the Sports Car Club of America. He swims a lot. He’s into music; way into it. He’s into damn near everything. What about the future?

“I’m planning on being rich. I’m writing two books.

One book is a cookbook and the other a biography. The cookbook is coming along quite well. It’s called The Chicken Magician: it’s 100 ways to cook chicken. I’m on number 50 now. (Then, as a continuing thought…) I’m buying a new Porsche.”

What made you think you were going to be rich?

“Well, I’ve been planning on being rich for a long time. For a long time, ever since I was a kid. I’m not rich, but I’m workin’ on it.”

His advice to new injuries?

“People in wheelchairs are just too heavy on being people in wheelchairs. Really! I think that any person, regardless of what his physical, economic or social status is, can improve that by just focussing on the positive things that they have inside of themselves, selling that to themselves, and then putting it out into the world. That works. It really does.

“If you go around saying that you can’t, then you can’t. But if you go around saying that you can, then eventually maybe you might.”

John Schatzlein#

In 1963, John was 15. He was a jock, outdoorsy by nature, and fond of camping and wilderness. Tree climbing was one of the accepted ways most of us outdoorsy kids increased our appreciation of our surroundings, and John had the misfortune to fall 50 feet out of a tree. He broke his back on a limb part way down, and continued his descent as a T5 para.

Rehab: University of Minnesota Rehabilitation Department, his subsequent employer. Seven months.

School: “I went through high school and I was fortunate. My high school was on the level, so there was no question about going to it. And with 1,300 AB’s around, I just became one of them. The disability really didn’t interfere with much of anything that I did. That was a big catalyst to come back and just be a part of what was happening.”

College: Southwest University, in Marshall, Minnesota. DVR helped. Again, there were no real problems. He graduated with a bachelor’s in psychology and sociology and was president of the student body. “There really wasn’t a question about whether I was disabled or wasn’t. At the same time, I had met a woman who was an able bodied gal there and that kind of capped it all for me. Once I found the person that was important for me and she accepted me just as another person, another male, from that time on, in ’67, I’ve never thought of myself as disabled. When that happened, it was just like, Well—I guess I’m whole. I’m normal. I’m average. I’m a little short and I can’t walk. That was my wife. We got married when we were seniors in college, and that’s almost 10 years ago already. Wow.” It should be added that John and Helen have one child and are hoping for another.

Work: Generally, since the specifics. boggle the mind, John works part-time in public health for the University of Minnesota Rehab Center and part-time on his master’s degree. Again very generally, he works on community resources, one-to-one counseling and teaching. Call him a rehab teacher, counselor and researcher, and you’ve got about half of it. He does more than that, partly because he needs to work. Except to tree surgeons, benefits and settlements are seldom paid for falling from trees.

So John augments his income and his professional stature by giving lectures around the country. Sexuality and Disability, for instance, and “I do a body image/self-esteem slide program that’s an educational thing, trying to get people to understand where they begin to develop their image and self-esteem. And why does it change, if there’s a traumatic or congenital disability, so that at 13 or 14 you recognize difference and begin to dislike yourself? It’s been well enough received that I travel all over the country doing these for nursing association groups and OT and PT schools.”

He also lectures and counsels on re-entry problems:

“The re-entry process is the responsibility of the consumer. It’s not the responsibility of the rehab professional to force the person back into the community. It’s the responsibility of the individual to put himself together, recognize that he is OK, and then go in and do it. The barriers are obvious. The physical barriers are there, the attitudinal barriers are still rather evident, but I think the re-entry process will get better as more and more disabled consumers go into the community and actually become part of it. The ease or the discomfort is resolved by more people seeing more disabled folks functioning just as everyday people.”

Recreation: “I’ve been camping a lot since the injury. We’ve done tent camping and wilderness camping because modern conveniences just don’t hit it off with my wife and I. So we’ve done some northern Minnesota stuff, up in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area and with the Outward Bound school. We put together a wilderness exploring kind of thing using the standard Outward Bound model as the thing that we wanted to try to duplicate with the disabled.”

The result was that the Minnesota Outward Bound School cooperated with John and his colleagues to provide 10 day wilderness courses for people with a variety of disabilities. “We met and decided that yeah, this could be a unique experience that would stress people to the limits of their physical capacity, at the same time showing them that they could survive in a wilderness area. Consequently, our theory was, it meant that they could survive in the community. They could survive back in their home environments.”

John admits that the tools don’t exist to convincingly test his theory. He does know that disabled people survive the course. “We just got a group of guinea pigs together. We tried it the first time and found out that we’d survived, that we’d pulled it off. And then we developed the program from there.”

A typical 10 day course might run like this:

The first three days are in camp, except that camp is on an island, so you have to negotiate a path and paddle a canoe to get there. Basic skills with ropes, canoes and rough terrain are taught.

The next five days are a land/water trek in the woods. Canoes, portages and some rock climbing, all done with minimal help from AB’s in the group which might include an amputee, a SCI, someone who is sight- or hearing-impaired or with MS. During this period each participant does a one day solo, meaning you are left alone on an island or a peninsula to deal with yourself for a full 24 to 30 hours.

Return to camp. Marathon. You commit yourself to a certain distance over a certain route, all of your own choosing, and it’s your responsibility to meet your own expectations.

Not surprisingly, a farewell blast. A party.

Information on the course is available from:

Minnesota Outward Bound School

308 Walker Avenue South

Wayzata, MN 55391

Here’s John Galland’s reaction to the course: “I was so high when I got back, I was just obnoxious.”

And here’s a little discussion on motivation and acceptance. Back to John Schatzlein:

“I think all people have the innate ability to be motivated. And I think that comes along at a certain individual’s time line. I think there’s a one to five year time line on the adjustment process.”

That’s exactly what a new injury doesn’t want to hear.

“That’s right. No way. We can speed it up to some degree, but people have to take their time. Some people may outwardly look adjusted, but if you talk to them five years later, they say, Yup, it was only about a year or two ago that I put it all together. Because we can fake what we look like on the outside.”

I wonder if after 10 years, you ask the same person, he might say Yup, it was only last year that I got it put together for sure. I thought I had it at five years, but I didn’t.

“I don’t think that you ever do totally. I think you continue to progress. I don’t think anybody ever 100% accepts, and I don’t think that should ever be asked of people. Do you accept your disability? I think the honest answer is No. And yet most of us aren’t ever going to say that.”

I will. I know others who will.

“Hell, of course you don’t accept it. You live with it, you cope with it and you do what you can to maximize your skills. But that doesn’t mean you accept it. For me, I have just developed a high level of coping. I can deal with whatever the negative ramifications of the disability are because all of us, as humans, have the ability to cope with stress. Those of us who are identified as Those Who Make It have learned how to cope well and not let it interfere with the rest of their lifestyle.”

That’s grittier talk than I sometimes let slip through my ever-inspirational grasp, but it’s also a real message of hope. Nobody likes the prospect of taking years to put a life back in order, yet it beats calling yourself a failure because you didn’t do it in a month. AB’s, too, take years to recover from setbacks, and the recovery period isn’t a cessation of living or growth. It is life and growth. Your injury hasn’t changed things all that much; it’s just made your goals more clear. See?

Binny Clark#

Binny Clark is not one of the new friends I discovered during my search for gimped America, but is an old and dear pal. A crony. We were brought together by a mutual need to make some sense out of messy lives. The focus of our interest was Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpoche, Tibetan teacher and founder of Buddhist meditation centers throughout the country. Rinpoche was a powerful and energizing force for both of us and dominated our lives for some time.

As the years went by, Binny moved into the heart of Rinpoche’s Buddhist community and I became a dropout. We still check each other out as often as possible, mainly to see what craziness the other has gotten into now.

You’re doing prostrations? Isn’t that kind of —uh —trippy? “It’s not as dumb as floating down rivers upside down in a kayak. And what about that Don Juan piece you wrote for Mountain Gazette? You going to do somersaults down waterfalls?” Beats wheeling.

And so on. For the purposes of this interview, Binny has agreed to omit (almost) all Sanscrit, freaky images and exotic practices which might make him sound like a religious nut. He’s not. He’s embarked on a long journey and has undertaken it with all the sincerity, good humor and commitment at his disposal.

So that you have some inkling of the journey’s present coordinates, Binny is now, and has been for two years, the liaison between Rinpoche’s headquarters in Colorado and his regional meditation group in Boston. Binny is the resident meditation teacher of over 100 Boston members, and both administers to and administrates his enclave.

Necessary details: Rolled a jeep in 1961, when he was 16. T11, spent one year in rehab near his home in New Hampshire. Graduated with his high school class, went to Dartmouth for two years, transferred to the University of Illinois at Champaign, won a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship and graduated with an MA in English and no desire to put his degree to use. “I got through the year and just fizzled.”

He lived at home for a year, then went to California during the flower child days. “I smoked a lot of grass and wasn’t getting much of anywhere. I put a lot of time into playing music and writing songs, sang in cafes; the normal route of a folky-type musician.” Things started going sour. “I became aware that I was doing it for uncomfortable reasons. It was a way of plugging my energy into something so I wouldn’t have to really look at the way the rest of my life was going, the idea being that if you make it as an artist, the rest of the 360 degrees of your personality doesn’t have to matter too much.

“I got an audition at Columbia, which I suppose for most musicians would be the light at the end of the tunnel, but for me it was the signal that I had to get serious about it or change directions right then. It wasn’t really working and I knew it at that point. It wasn’t the way I wanted to spend my life.

“During that same period, when grass and music began to run out as a way of stringing day to day, I’d been reading all this sort of hip literature —the drug literature, of course, has a lot of pseudo-spirituality involved with it —but in reading about these various spiritual quests, there was a great deal of trippiness. Instant enlightenment schemes. Kentucky Fried Nirvana. The more you looked into them, the more silly they looked.

“I did go around to various groups in California, and I guess the thing that finally impressed me that maybe something could be discovered through these various eastern religions that were trickling in at that time, was Ram Dass (aka Richard Alpert, Timothy Leary’s sidekick in LSD experimentation), who had just come back from India. He’d had a very strong experience at the time, and it was impressive that somebody could be quite that alive.”

Were you feeling unalive?

“Yeah, I think so.”

What sort of possibilities was Ram Dass talking about?

“That’s more difficult. I think it’s that there’s more to being human than the convention of plugging into the going culture of the day, living your life out and dying. And if you look at it, most cultures do say that.”

You had done some meditation before you met Rinpoche?

“Yeah, that was Ram Dass. My impulse, when I heard him that first time, was to follow part of his advice. He said the best way to meditate was to go off on retreat. So I went up to a mountain pass in Montana and camped out for three weeks — with mosquitoes, bears, a lack of water — but basically I had no idea of what meditation was. And for about a year after that, I tried various schemes. I’d read a book, and it would seem very good, and I would try it out for three weeks until I read the next book. Then I would try that. By the end of the year, I started getting negative hallucinations and various disturbing things and I knew then that I had to find somebody who had direct experience with meditation.

“Now I thought at this time that you had to go to the East to find someone who was genuine. So I thought —I’ll get a ticket and go to India — having no idea what I’d do when I got there. But then I got a brochure from Rinpoche’s meditation center in Vermont, so I went there. When I finally met Rinpoche, it was the first real, direct experience I’d had of meditation and spirituality being something that was very immediate and down to earth. Not exotic. It’s very well suited to the ways of this culture, even though it does progressively change the way you look at this culture.”

What attracted me to Rinpoche was that his psychology made sense. It had an enormous clarity and consistency with my experience. I never did see it as a religion, which you always said is why I became a defector. As I recall, you called me a schmuck. I was deeply hurt.

“Oh? It’s not a theistic set-up. It’s not looking to someplace else than the world. It doesn’t involve any kind of withdrawal from society; it actually revels in the juices that enliven and hold society together. Nothing is rejected in anybody’s psychology. Buddhism says it’s not a question of changing what your personality is at all. That means that there’s no embarrassment about anything that’s going on within your psyche. You can use positive or negative components of your personality as they are. Well, that’s very different from other philosophies and religions that I’ve looked at. There’s a kind of poverty in their thinking…”

… Out with the bad and in with the good?

“Right. Buddhism doesn’t do that. It pushes everything back to the individual and says, Look at who you are and learn to value that. It’s much richer than you’d realized.

“In my case, that was extremely important, because one of the problems of disability is the whole question of self-esteem. Who you are. That’s the real crisis, because suddenly your whole idea of what you should be, your version of yourself, is changed radically. In everything I’d tried before there was that escapism quality of wanting to get some focus that would blot out the distressing, disagreeable areas of who I was. Meditation and Buddhism has been good for that because it says you can’t reject that. If you try to de-emphasize the negative things and have this positive attitude in just one area of your personality or your life, the other part is bound eventually to catch up. This is fairly understandable in terms of western psychology. It’s just repression. If you blot something out, eventually, it pokes its head out somewhere else.

“What it means to a disabled person is there’s much more appreciation of who you are in the moment rather then what you are vis-à-vis social roles or social models. You’re not as apt to be caught up in what society or Hollywood or Madison Avenue think you should be. You’re much more apt to stay with who you actually are and to value that. It’s a completely individual discovery. There’s no real way you can communicate that out to other people except inasmuch as you seem to be on good terms with yourself. That does communicate.

“So gradually you find that you like yourself more. You’re more friendly with yourself.”

I’ve always liked that idea — making friends with yourself.

“It doesn’t mean that you comfortably accept yourself with all your insecurities and paranoia. Making friends with yourself means that you can handle your life, that you don’t have to be buffeted around by a kind of cramped view of who you are.”

Well dammit, Binny, here we are all making friends with ourselves and developing a more accurate model of the world, but how come you’re not becoming a contributing member of society by producing a lot of goods or services and paying a lot of taxes and making the system work better? Are you anti-American?

“What kind of interviewer are you? OK, that’s a good point. The conventional view is that it’s escapist, that it’s turning one’s back on the problems of the world, on the starving children in China, the boat people. The (Buddhist) idea is that you can’t really begin to genuinely help the situation in the world as long as you’re caught up in your own neurotic patterns. (In Buddhist teminology, Neurosis is something we all have and share. It denotes unclear perception of reality and its attendant behavior, and is thus less pejorative than western psychology’s narrower use of the word.) The initial thing that has to start happening is that people have to stop polluting their environments in the sense of spreading their own neurotic view of things onto other people. Most of the ills in the world today come out of basically that. People are constantly pushing their trips on the rest of the world for all kinds of ideological and moralistic reasons.

“In this society, one of the main moral forces at work is the idea that everyone should conform to the American Dream, that the only way to be a healthy, whole person is to be part of the productive juggernaut.”

What’s this got to do with disability?

“People who are disabled have a very positive position. They can actually break loose from that whole insidious kind of pressure. It’s because the fact of the disability is inescapable that the disabled person isn’t as easily seduced into the whole sleepy view of what it is to be human. You can’t be lulled into a kind of complacent acceptance.”

Of other people’s values?

“Sure. A lot of the standard assumptions of what it is to be a human being in the twentieth century in the West are based on fairly illusory value systems. I read somewhere that the average American sees or hears a thousand ads every day. There’s a great deal of money spent to hold together the vision that this is the way to live. It’s the good life. Grab for it. And for the disabled person, it’s agonizing to see this consistently reiterated version of the successful man, the successful woman. If he takes the barrage (of media) seriously, a disabled person can’t measure up to that.”

Sure he can. He can earn a lot of money, he can buy everything that Madison Avenue is trying to sell him…

“Right. And when he looks at himself…”

… he’ll feel just the way any intelligent able bodied American ought to feel. Shafted.

“Ok, but we have an infinite capacity to filter out disagreeable self-reflections. That’s why it’s so prevalent to have disabled people depend a lot on drugs and alcohol or personality quirks. You know, there’s the Cheerful Cripple who’s always happy or the Jock or the Completely Self-Reliant Proud Gimp…”

Or the Holier-Than-Thou Neo-Buddhist Gimp…

“That’s right. It could be. But the point is, you really do have to look very closely at what’s going on, because the filters go up almost without your realizing it. And suddenly you’ve created a personality for yourself which isn’t quite what you had in mind.

“It’s not just disabled people versus able bodied — every person who’s ever lived has had awkward moments when his roles suddenly fall apart and he’s left with this panicky feeling that he’s kidding himself. Meditation is the only thing that I’ve found that works directly with that kind of panic. The only way we can get that neurotic mess into the light of day is to actually stop and look at it, not just speeding on trying to maintain the pleasurable states. The idea of looking at it is not to rub our noses in our own shit, but just to find that that shitty area of our lives is fairly workable. We can handle it without having to freak out every time it pokes its head up.”

I’ve been thinking of becoming a Moonie. Do you think that would help?

“Depends.”

I’ve been thinking of changing from vodka to gin. Are you interested?

“Certainly.”

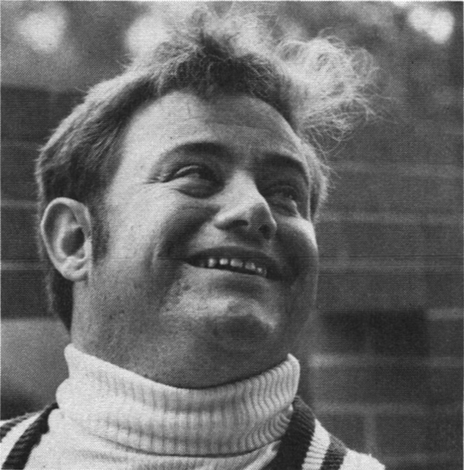

Hank Atkinson#

There’s nothing flashy about Hank except that he’s obviously alert and healthy and has a quick smile that somehow manages to spread slowly across his face. Got that? He looks as if he might be a computer technician, a stockroom manager or a teacher. He’s a geotechnical engineer and a T3,4 para from a car accident when he was 20.

Another thing. He’s been a para since 1959, and has never been hospitalized since then. Lots of experience here. Here are some of the things he has done:

He resumed his education. “I was in the hospital for four months, got out, and I knew I was going back to school at the University of Illinois. But I had about three months that I spent at home. That period of time I really didn’t have much to do and that was a time of deep depression for me. Once I got back to school taking classes, I was so busy and so tired that I didn’t have time to be depressed about anything.” He emerged with a doctorate in civil engineering.

He’s been appointed to the research faculty of the University of Colorado and has a private consulting practice on the side. His area of interest is underground coal mining and he’s widely recognized in the field.

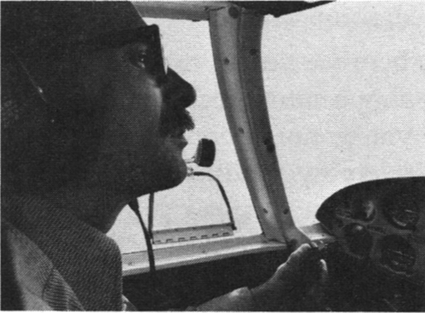

He flies a Piper Cherokee Arrow which he bought with some friends. The adaptive device is a simple lever mechanism which takes him five minutes to install or remove for the convenience of his co-owners. He does his own pre-flight from the chair. The wings are low, the transfer is a cinch and he can pull the chair in after him.

“In all the flying I’ve done, I’ve never had anyone say You can’t do it. They say, Show me you can do it.

“It’s really a freedom. I’ll fly to some airport, park the airplane and get out, and people really open their eyes and look, and say That’s neat, yet since I’ve flown up there and done it, they treat you like a pilot, with a professional sense of respect.”

Hank works at his health. He swims three times a week, 600 yards each session; it keeps up his cardiovascular and pulmonary reserve and he enjoys it.

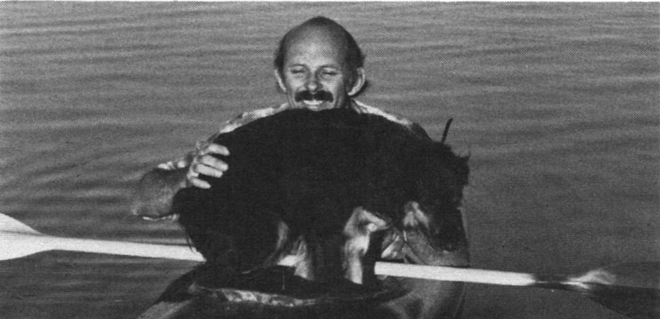

He’s recently taken up kayaking and hopes to use the boat as a way to fish in seclusion on lakes where road access points are overcrowded. He’s boated on two rivers now, rivers with real rapids, and has an expanded idea of what kind of water he’s capable of running.

I asked him how, in dealing with new clients, he presented Hank-as-Hank instead of Hank-in-a-wheelchair: “Certainly people are surprised when they know the type of work I do, then see that I’m in a wheelchair. In a lot of cases you have to be the person who sets the tone of the meeting, be more assertive.” He feels that many people experience initial discomfort with his chair, then promptly forget it. “The main thing is to have an aggressive attitude. That doesn’t mean you have to be pushy in any sense of the word, but you have to go out and make things happen yourself.”

And that quick smile is spreading slowly across his face right now. He’s just unloaded his kayak from the roof of his Saab, wheeled it to the edge of a lake, and is getting ready to push off and make things happen. He’s probably got a fishing rod stashed in his boat.

Bob McGinty#

The day before the high school senior year began, the captain and star quarterback of the football team called a practice. It was a hot September day in New Jersey, so some of the team went to a local swimming hole to cool off after practice. The captain dove in, warned the others that it was shallow, then dove in again.

A few hours later, captain Bob McGinty was chatting with the doctors in the operating room, having rudely interrupted their ongoing discussion of what foods each had enjoyed for dinner. He told them that he had to be out in three weeks to make the first game of the season.

“I remember the doctor saying, Son, you’ve seen your last of playing football. It didn’t dawn on me at the time; what’s he know? I had a broken ankle when I was a kid, and it healed.”

And as the truth sank in: “It just seemed that my world came crashing down, because at that time I had no concept of what paralysis meant.” He knows now. He’s a C4,5, and his accident happened in 1956. He was 16 years old. Bob’s story, like many in this book, wouldn’t be likely to happen today. But in 1956, being a quad meant you had to be tough.

Bob’s “rehab” consisted of tongs, traction, a laminectomy and a Stryker Frame for six months. That’s all the hospital could do, so they sent him to a convalescent home in Delaware which was primarily an elderly care facility. He spent two years there and was discharged to his home. His parents bought a vacant house, modified it as necessary and took care of his attendant needs. Schooling seemed like the next logical step, which brought him to the State Department of Vocational Rehabilitation.

“When I was discharged after two and a half years in the hospital and I applied for assistance from Voc Rehab, they refused to give me that assistance because I was too severely disabled. And I accepted that, unfortunately, at that time.”

Thus began 10 years divided between two endeavors. The first was to convince Voc Rehab to accept him as a client and the second was to become an artist.

Becoming an artist was much the easier of the two. He took a correspondence course, started painting with a mouthstick and picked up some blue ribbons at art exhibits. The newspapers saw his work, featured him in print and Bob was able to sell paintings. It was never a real living, but it covered some expenses and gave him spending money. He painted all through the sixties.

And he battled Voc Rehab. For 10 years, they repeatedly turned down his requests for help in schooling. He had thought of going to art school.

“My first (DVR) counselor came to my house, looked at my paintings, and said Who the hell do you think you are, Van Gogh? It really shocked me that a rehabilitation counselor would say that. He said, Don’t you realize that artists are on every other corner selling their work for 50 cents? How do you expect to ever be independent by painting? This came from the agency whose whole responsibility is to further, assist and pursue employment for disabled people. He said, Why don’t you be realistic? The famous words, WHY DON’T YOU BE REALISTIC? You’re a cripple! You can’t do anything! Finally it dawned on me that the only way to get any assistance from them was for me to take the initiative.”

He did. He compiled extensive documentation of what other states did for their clients, then flooded Trenton, the state capitol, with facts and precedents. He made his own appointment with a psychologist, took a battery of aptitude tests and sent the results to Trenton. He talked to admissions directors at all the schools in his area to see where he could be accepted, and then let the state know about it.

“I kept telling these directors of admissions that I was coming as a student, and I didn’t know how I was getting there or how I was going to pay for it. So finally, I threatened Voc Rehab that I would picket the state capitol if they didn’t accept me as a client, and it seemed right after that, they said they’d give it a try.”

Ten years after first applying to Voc Rehab, he entered a two year community college. Once there, his grades generated scholarships and Voc Rehab paid for lunches, transportation assistance and adaptive equipment. He was class valedictorian the year he graduated.

Which brought up the possibility of an undergraduate degree. Voc Rehab agreed to stay with him, and he went to the University of Miami. There he raised hell, along with Stephen Epstein and others, and succeeded in making the campus almost completely accessible. He took a liberal arts program, earned more scholarships and graduated Magna Cum Laude.

Just as Voc Rehab was starting to relax, Bob decided to take the Law School Admission Test and was admitted to the University of Miami Law School. That sort of committed Bob to becoming a lawyer, which in turn committed Voc Rehab to pay expenses.

Whatever gave you the audacity to think you could become a lawyer?

“Stubbornness. I didn’t want to end up vegetating and looking at four walls. Life is too precious to do that. I have so much curiosity that I want to explore that I just wanted to break out and become involved in things outside my own mind.”

Bob was the first DVR client from New Jersey ever to receive graduate assistance. Had the agency people known just how long a ride they’d get taken on, they might have intensified their initial resistance. Yet Bob was becoming a feather in their corporate cap, and probably was starting to look pretty good to them.

Any law school is a den of obsession and cutthroat competition, and it wasn’t easy for Bob. Law students virtually live in the library, and he needed help just to get a book down from the shelf. But, “I figured I could always outwork able bodied students, because there were so many other activities they were involved in. It took me longer to do things, but I knew that that commitment had to be made if I was going to compete with them.”

In 1978, Bob passed his bar exam.

Then started the job search. “It seemed as if I had an easier time getting interviews than some of my classmates, but when I did appear for the interview, I was shown pretty condescending attitudes. They wanted to know if I could be a diligent, dependable worker. I think they thought of absenteeism, there would be times I wouldn’t be able to get to work, there would be transportation difficulties on some jobs —this was mainly in the private sector. I noticed a difference when I applied for jobs with government, or even in the judiciary system. They were very receptive.”

Bob decided to go to Washington, DC, since they do more government and judicial work there than most anywhere. His first interview was with the Small Business Administration, and they wanted him. He liked the people, liked the corporate and commercial law the job dealt with, and accepted outright.

In this day of Affirmative Action, he offers this candid observation: “I think my being a cripple is one of the factors they wanted. Maybe they wanted a showcase. They’re telling all the private companies and corporations that they have to hire the handicapped and they had to live by what they preached. But I think they were truly interested in me as a person. I think they were all aware, by the credentials on my resume, that they were getting a competent and dependable employee.”

There’s still something wondering and childlike about Bob, as if he can’t believe where he’s come from and where he’s gotten to. He pauses briefly, his face does something between laughter and tears, and his happiness bursts out like sunshine: “After almost 23 years of being a quadriplegic, I’m now earning a living, I’m paying taxes, I’m off the public dole and it gives me great satisfaction. I see my prospects in the future are very bright, and I’m very satisfied with my position at this time.”

And he likes being Robert McGinty, Attorney at Law.

And he’s sincerely grateful to the New Jersey State Department of Vocational Rehabilitation.

Rob Lewis#

In 1969, members of the National Honor Society thought so highly of one of their teachers that they presented him with the Teacher of the Year Award. For a serious young man named Rob Lewis, it was a recognition to be savored.

Rob’s a T7,8 para from a car accident in 1964. He was a college sophomore at the time. A year of rehabilitation and part-time studies later, he transferred to the University of Missouri, picked up a BS in Education, briefly attended law school before deciding that teaching was what he wanted to do, and returned to Missouri to complete his master’s degree in guidance and counseling.

Rob’s transition from schooling to working was typical of wheelers going on to higher education. Hank Atkinson, a para with a doctorate, compared extended schooling with preservation of “the safe haven of institutional protection.” Rob didn’t make that comparison, but there’s something similar here:

“For a long time I was very hesitant to go to work, not because I disliked work, but because I enjoyed school and the easy life more. So I think that’s one of the reasons I went to law school and went back for my graduate degree. And then I got to the point where I finally had to get a job.”

It wasn’t too tough. He was hired at the first school he applied to: “I encountered absolutely no resistance whatever. As long as I could perform my job, as long as I could communicate with students, that’s the main thing.”

It has obviously worked out well, for Rob’s been at the same school for 10 years. About the time he started teaching, he married Riva; another relationship which has lasted. He has yet another relationship which he takes very seriously, that with his students: “I’m very obvious, of course, but I try to make a point the first day or two of class of telling them precisely how I got to be in the chair and letting them know that even so I’m a competent person, I’m married and I live a very normal life except that I have a few extra pieces of equipment I carry around with me. I think students are very readily able to accept that.”

And after 10 years of teaching? He’s taking his sabbatical this year; he’ll use it to work in library media at the University of Colorado. But he’ll be back. “The freedom being an educator gives me is that thing which I value more than anything else. I always come back to education. I enjoy the contact with students, I enjoy the caliber of people who work in that situation — other instructors —so I guess there is really not another job now that I would consider taking.”

Since Rob teaches philosophy and psychology, I’ll relay his word on motivation without comment: “There’s no such thing as an unmotivated person. There are only persons who, for a period of time, reach a state where it seems that there’s nothing that can be done. And that’s very real. But I also see it as not the truth. Maybe it’s like physical maturation. Some people bloom earlier than others, but they all bloom. I guess I would say that’s what motivation is all about. It’s just when it will occur; it’s not if it will occur. It will occur. Sooner or later, the bad becomes better and one success leads to another. And another and another. The capability is there, and the will will come.”

Now, in 1979, I’ve returned to a classroom for the first time in over 20 years to watch Rob teach. It’s a relaxed setting; students wandering in, chatting with each other or with Rob, sitting where they want and looking pleased to be there. Rob starts winding up. His subject for today is sadism and masochism, and within a couple of minutes he has every student in the class confessing to acts of sadism in their lives. Rob clowns, cajoles, reasons and rages, and has the kids doing the same. He bludgeons them with words and logic and showmanship and their own participation. And all the time, he’s moving all over the room. I’m taking pictures, and it’s like covering a sports event. Fast and exciting. The students love it. Rob loves it. I love it.

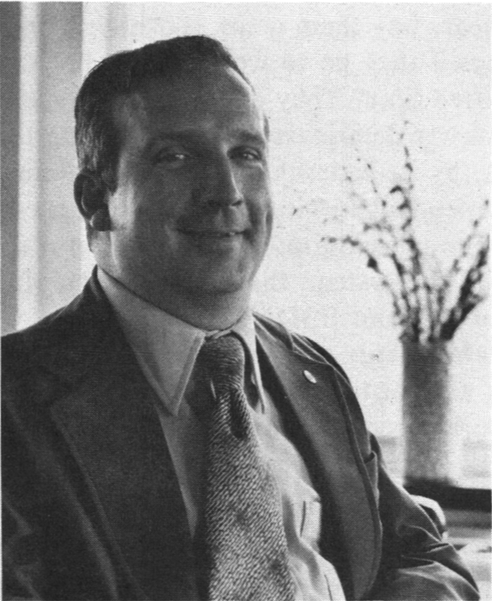

Elmer Bartels#

Remember the DVR guy that at least half the people in this book have bitched about? That guy who doles out benefits according to whimsy or rigid rules, but never according to human potential? That guy who sees every request for funding as creeping socialism and every success story as his own moral victory? That guy who doesn’t want his clients’ education to surpass his own? Well here he is. Elmer C. Bartels. He runs the Massachusetts Rehabilitation Commission. He is the Commissioner, or, in the language of the day, he is the State Director of Vocational Rehabilitation. The buck stops here.

And stop it does. In an hour and a half, this man spoke more sense about SCI, its pitfalls and opportunities, its history and future, than I’ve heard from any single source. His waters, as one of his friends remarked, run very deep. He seems like a good person to act as final spokesman for us all; our valedictorian.

Details: Hockey accident in 1960. He was 22 years old, a senior at Colby College in Maine. C4,5.

Rehabilitation: 12 months at two different Massachusetts hospitals, and one month at Rusk. He calls Rusk his finishing school: “The one thing they did for me at Rusk was to say, basically, You can do what you want to do and don’t let your disability stand in your way.”

One of the things he wanted to do was get married, which he did 13 months post-injury. He showed exceptionally good sense, in fact, by marrying one of the nurses he’d met during his recent tour of rehabilitation facilities along the eastern seaboard. He is still happily married and has two children.

1962: BS in physics, Colby College. 1964: MS in physics, Tufts University.

Then followed three careers. After graduation, he spent four years working in nuclear physics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. MIT enamored him of computers, so he switched over to a second career at Honeywell Information Systems, manufacturers of computers. At Honeywell, he started as a senior systems analyst and was promoted to department manager. In January, 1977, he was appointed Commissioner of the Massachusetts Rehabilitation Commission.

Elmer’s Vitae sheet is awesome. He is a founding father of the Massachusetts Association of Paraplegics and the New England SCI Foundation. He holds honorary doctorates from both Colby and Tufts, about a dozen awards honoring his work in SCI and rehabilitation, and has authored or co-authored articles, papers and monographs ranging from rehab-centered topics through The Nature and Use of Conversion Software and The Design of an On-Line Computer Based Educational System for Industry to Analysis of Fragmented Analog-State Resonances by Coupled Optical Equations with Effective Nonlocal Potentials. Enough?

So how did careers in nuclear physics and computer systems prepare him to run a thirty-five million dollar public agency? Elmer gives the credit to his promotion to department manager at Honeywell and to the person who took the risk of offering a high level quad that position. “It allowed me to develop management skills and perfect them to the point that coming to do this job was a viable thing to do. It made sense to me and to the state and to the governor who appointed me.” It also made sense to the subsequent governor, who made a clean sweep of the existing state bureaucracy in 1979 but retained Elmer Bartels.

“During my whole career, I’ve had kind of an avocation in the area of SCI and developing systems of care, standards, resource documents and general improvement of the system as it impacts on the lives of people who have become SCId. So I have flipped from my computer career over into a rehabilitation career. My hobby is now computers and my work is rehabilitation.

“One of my priorities in running this agency is Consumer Involvement, developing a philosophy whereby the professionals in the agency and the clients served by the agency can work together on mutual issues — advocacy, quality assurance of this agency, policy considerations —just a whole host of things. The essence of it is, we can’t do it alone. The job’s too big; we’ve gotta do it together.”

One of Elmer’s on-the-job triumphs is the creation of a 100% state-funded program paying for personal care attendants. (To my knowledge, California is the only other state doing so.) To many quads, this benefit is the sine qua non of holding a job. The state is richly repaid through taxes the new employees pay and by gaining new contributing members.

On motivation: “Some of it is the lifestyle people bring to an injury. People who are accomplishment-oriented tend to do well. People who are not accomplishment-oriented tend to not do so well. But that’s not the whole story. If you take someone who is accomplishment-oriented, and you don’t provide a light at the end of the tunnel and provide a perspective of what they can achieve providing they attempt it, if they can’t see where they’re gonna get, then they won’t try to get there. But if they can see it, they’ll go get it.”

And for the non-accomplishment-oriented?

“That’s where the creativity comes in; it’s sort of a step-by-step process of becoming successful almost in spite of themselves. But that’s a gradual approach, setting short-term objectives. They have to be given intermediate goals that they can achieve in order to reach for the next step. And that is the motivator: having accomplished once, people will attempt to accomplish again. And again and again and again, if the steps are small enough.”

Some people seem to just stay devastated by their disabilities.

“Some of them, the system has failed them in providing the goal-orientation, the gradual successes along the way. And they’ve been booted in the pants so much that their emotional elasticity is gone. They’ve met with failure after failure after failure. For instance, someone gets pressure sores from day one, which is medically inexcusable, and that issue comes back to haunt him again and again and again. Every time they get up in their chair and begin to get going, the pressure sore issue comes back again. That could have been prevented by proper medical care, and the physicians that allow it to happen should be sued. They’re not. They should be. It happens too often, even in our advanced SCI systems. Another issue might be bladder infections, where improper bladder care has occurred from day one and comes back again and again and again. Those things are imposed by error, so the system has failed them.

“And there’s another side of it. That is the benefits issue, and I see this more in terms of the VA. For the service-connected injured, they have a benefits structure that will pay them up to twelve or thirteen thousand dollars a year, buy them a car and buy them a house. They’re nuts if they go to work. And what do they do with their free time? They drink, they sit around all day and they slowly deteriorate. They’re killing themselves. So the VA, by its benefits structure, is forcing people to live in a dependent fashion. If they’d cut the benefits out on a gradual withdrawal basis, and put some incentives in the system, that would be helpful. That’s also true of SSI and SSDI.”

How about kids who never did want a higher education, who just wanted to finish high school and join the work force and have some loose change in their jeans?

“People without high school diplomas have developed businesses as a stock broker or started a mailing business —it depends on how much you are motivated to accomplish. Just because you happen to be a C6 quad doesn’t mean that that’s the end of productive living. It’s merely the beginning of productive living, only in a little bit different form than you might have thought. And it may, in fact, be a better quality life in the sense that instead of living in the army for 20 years and then going on retirement, you may be more productive in terms of contribution to yourself and society.”

Elmer is well pleased with legislative progress over the last 20 years, especially that affecting architectural barriers, services to the disabled, education and civil rights.

“I think there’s enough structure there, from a legal perspective, that we don’t really need that much more. We’ve got enough of a legal sledge hammer to get people’s attention. The issue now is getting at attitudes, and the only people who are going to change attitudes are the disabled as they take positions of leadership in the community. People have to get out and take their own personal responsibility to change the attitudes of people around them. If you take that and build on it — that every individual that is disabled is indoctrinating society —it will do the job in 10, 20, 30 years. Because there are more disabled people, with more friends, more people they come in contact with, and more attitudes get changed. That’s what I see will happen over the next 30 years. And we’ll look back, 30 years from now, and say this was the Dark Ages with respect to attitudes toward handicapped people.”

Love your chair? Hate your chair? Elmer, as usual, aims at the dread heart of the matter: “Living in a wheelchair for the rest of your life is not significantly problematic. People in wheelchairs work, they get married, they have families, they do a lot of things. Living on wheels becomes a non-issue. It’s a damn nuisance and that’s the extent of it. And you can do what you damn well please.”