Lives II#

Gene Tchida#

The Special Services for Disabled Students program at the University of Arizona (see preceding section for description) is coordinated by Gene Tchida, a C4,5 quadriplegic with the best possible reason for being helpful. He came so close to spending his life in a nursing home, was so victimized by primitive care, was so uninformed of his real abilities and expectations and was so deprived of opportunity that he desperately wants to be sure that these things never happen again. Ever. To anyone.

Gene was in an auto accident in 1956, when he was 16. Here’s his “rehabilitation” history, which should be read with the understanding that his accident predates the advent of rehabilitation as it is known today.

General hospitalization in Globe, Arizona. Tongs and traction immediately applied. Moved to Good Samaritan Hospital in Phoenix, which then offered only general hospital care but at least had a Stryker Frame. (Good Sam’s SCI Center, established later, is now a symbol for enlightened rehabilitation.) Transferred to a Crippled Children’s Hospital which was custodial, not remedial. “It had the look of an old people’s home with young people in it. There I was, 16 years old and looking at something pretty bleak.” Indeed, it was very bleak. He couldn’t feed himself. He’d never heard of hand splints. He was pushed wherever he went, because electric wheelchairs weren’t part of what the hospital offered. There was one therapist who knew enough about the fledgling subject of rehabilitation to get him released to family care at home after six months.

His family was supportive, took care of his attendant needs and encouraged him to finish high school on a home-bound program, which he did. That completed the goals he had set for himself before the accident. He’d toyed with the idea of joining the Navy, had never considered college, nobody in his family had ever gone on to higher education, and he had no idea what to do next.

Friends and parents suggested trying college. He made an appointment to see the assistant dean of a nearby junior college, but the dean’s office was completely inaccessible. “That was a frightening experience. How was I going to school when I couldn’t even get in the door?” That experience spun him into seven years of “semi-vegetation,” as Gene puts it. A lot of reading, a lot of television and a lot of frustration. A lot of killing time.

Gene’s older sister, always concerned, started asking around the State Department of Vocational Rehabilitation. After a psychological assessment, he qualified for three months of intensive occupational and physical therapy at Rancho los Amigos Hospital in Downey, California. Gene credits his sister and Rancho with turning his life around.

Rancho: After eight years, Gene was, for the first time, exposed to real rehabilitation. After eight years, he was, for the first time, outfitted with hand splints and an electric wheelchair. After eight years, he could go somewhere without asking.

“I saw rehabilitation, and I saw many young people my age, some younger, some older, who had similar situations. It opened all kinds of doors. I could see that there were areas that I could move out into. There was a sense of identity, a sense of importance, and the relationships that developed started to show that I was normal on the inside whereas there was some physical loss on the outside. That was really eye-opening for me.”

The rest of it went quickly. He enrolled at Arizona State University at Tempe that summer as a 25 year old freshman, and graduated in psychology. Got his master’s at the University of Arizona in Rehabilitation Counseling. Worked into the Special Services program during its infancy. In 1972, he married Linda: “I’ve been married now six years. Ten or twelve years ago, marriage was, to me, a completely foreign idea. I quite candidly did not think that a person who was a quadriplegic got married. I think it demonstrates as much as anything my lack of understanding of what was achievable, given a person’s will and desire and motivation and willingness to take chances. Today, I think it’s a very natural state of affairs for me.”

How would he compare his own satisfaction now with, say, his satisfaction in 1959?

“Night and day. Literally. Then, I couldn’t see anything. I couldn’t see the next day, the day after that. I had no feeling for future, for goals. Now, I feel that I’m really limited only in the sense that I limit myself.”

How does he feel about severely disabled people adding the difficulties of schooling to the existing difficulties of disability?

“I don’t look for guarantees. I look for chances. And I think that’s what I would like to ensure —that individuals get a chance. It may be a chance to fail, but at least it’s a chance.”

So Gene seems to have experienced the ultimate satisfaction — having narrowly escaped life imprisonment in semi-vegetation, he has forged a life which gives him and others the opportunity he was almost denied.

As we leave his office together, he talks enthusiastically of the new house he and Linda are building. As we pass the receptionist, she asks him a question in sign language. He answers, apparently using substitute signs to offset his lack of manual dexterity. For me, this is humbling and heartwarming. If Gene Tchida, who definitely does not have the good hands, has time to tackle sign language because some of the students his office serves are hearing-impaired, then the rest of us can surely summon the wherewithal to rejoin this world of magnified opportunity with joy and abundant energy, simply because people like Gene have made it possible. For anyone.

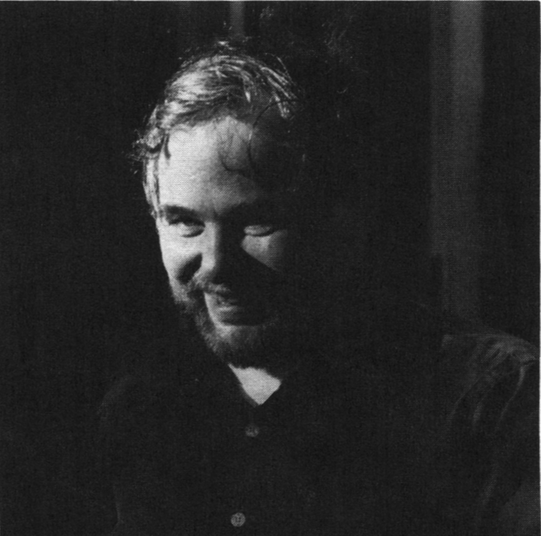

Larry Bryant#

Larry Bryant works in the belly of a bureaucracy and is proud of it. He wears the uniform —three piece suit, polka dot tie, patent leather shoes and a gold watch chain. There are a couple of apparent anomalies: quiet articulation, decisiveness, directness and sensitivity are not qualities that I always expect to find in bureaucrats; and then there’s the gold earring…

Larry’s been through a lot of changes. He comes from an educated, fairly affluent family in Atlanta. There are many executives in the family, several holding PhD’s, and he was expected to fall into the same mold. Predictably, he rebelled. He learned how to make a zip gun at the age of 12, spent a lot of time on the streets in and out of trouble, participated in civil rights efforts and generally avoided anything that smacked of the establishment.

In 1961, he moved to Los Angeles to see if he could mellow out a little. He was diving into the ocean from a 20-foot cliff with some friends, misjudged a wave and began a new life as a C4-6 quadriplegic. He was 16.

Since that time, Larry did his rehab, finished high school, got two undergraduate degrees, earned a master’s in rehabilitation counseling, counseled emotionally retarded adults, participated in Project Hope, which was an effort to keep delinquent kids out of jail, moved to the Los Angeles Mayor’s office, which was beginning to bring the handicapped into civil service jobs and now is a deputy compliance officer with Affirmative Action for Los Angeles County. It’s a responsible job with expanding opportunities, and he likes it.

I wanted to know about some of the missing details, such as his rehab at Rancho los Amigos.

“Man, I spent two years at Rancho. I really didn’t want to leave, you know. I became so dependent on people doing things for me that it was difficult to leave, to get back out there. Two years of that just about did me in.”

He did succeed in finishing his last two years of high school while at Rancho, but feels they should have kicked him out earlier, an opinion no doubt shared by Rancho. They, like Larry, have changed since 1961. Here’s some hindsight:

“Things are going to be only as bad as you make them. You can sit in that hospital room and vegetate the rest of your life. You can deal with nurses, with doctors, with other patients who are just there to create their own little world —but whatever you accept is because you make the choice to accept it. Therefore, if you want something good to happen, you can make it happen. The things that I wanted and the things that have happened to me are basically because I made them happen, not because I was any Superman. I believed they could happen.”

But what if I’m not really bright, I never wanted to finish high school, I’ve got no career objectives and now I’m a quad?

“Hey, I didn’t believe I was bright. I didn’t believe that the State Department of Rehab would send me out of state to go to school, I didn’t believe that there was a welfare system that would support me. There were a lot of things I didn’t know, but I started to ask questions and, in some cases, to make people come up with an answer for me. You know, you can search and search and search sometimes, and look in the wrong place. But you’ve gotta make things happen for you, you’ve gotta believe that there are things out there for you.”

This conviction didn’t arrive in one flash of insight. He started with correspondence school: “I did about a year and a half, then realized that I didn’t have to sit in a back room and type this correspondence work. I could actually go to a campus and mingle with the other kids. And I did and it was great.”

Larry picked up an AA in business, a BA in experimental psychology, then traveled to the University of Arizona in Tucson for his master’s in Rehabilitation Counseling. How was it?

“Fan-tastic. That year that I went away to Arizona was probably the best year that I’ve ever had. It allowed me to not just be on my own again, but to think freely. That was the best time I ever had, aside from what I’m doing now with the young lady I’m with.”

Larry is quick to credit Gene Tchida and his department for much of the good times. “They helped me get an attendant before I got there, find an apartment; they were really nice people. There were 360 handicapped students on campus and they had everything for us. As much recreation as any other student took part in. You did everything anybody else did. You were slowed down but you weren’t really limited.”

He didn’t date much at U of A, not because he didn’t want to, but because he did a two year master’s program in one year. That was a pretty demanding goal, and he’s very proud of its accomplishment. But no time for dates.

That, too, has changed. He’s getting married very soon, loves to talk about Esther, his fiancee, about what they do now and what they’ll do later. And about how it used to be:

“I used to sit back in the hospital room and dream about going on dates, taking a young lady out somewhere, and it never seemed to be a realistic thing to happen to me. I used to think that I would never be able to have any kind of relationship with anyone. But it has happened. As I became more confident in myself, understanding what goes on around me as well as in a relationship, it just seems that it was a natural thing that I would someday find somebody who was like me, who liked the same things I liked, who accepted me as an individual and only looked at me secondarily as an individual who is disabled. And it can be the same way for anybody.”

There’s a stiff entrance exam getting into Larry’s office. It’s in the Los Angeles County Administration Building, a structure which makes the Pentagon look as complex as a gazebo. After the guard station, there’s an underground maze of parking levels and ramps designed by a storm sewer engineer, and elevators which can take you where you want to go only if you take the correct elevators in the correct sequence. The office is on the seventh floor, looks out over the city, and rattles constantly from the throbbing of the helicopters that hover about like mosquitoes. Or maybe the earthquake is finally upon us. I feel paranoid in these places.

Larry, on the other hand, looks very much at home. He is a little surprised to be here: “It was just not in my program to be sitting here with a three piece suit — with an earring in my ear, sure —but being here and dealing with other three piece suit types.

“I came on as the County’s expert for the handicapped. This was right after the Rehab Act was enacted. Basically my function is to oversee grievance procedures for individuals and to protect and safeguard the rights of the handicapped for the County. That includes advising the Board of Supervisors, advising the Affirmative Action Officer and the Board on handicapped legislation, on rights, accessibility, regional accommodation, that sort of thing. Sometimes I feel like the expert. Sometimes (groans) I don’t know.”

He feels that his office does a good job, but is hindered by limited budget and staff. “We get things done, but not in the volume and quality, sometimes, that we’d like to get them done.” It’s easy to see why: 21 employees are providing services to 65,000 handicapped people in the County.

Are there handicapped people out there who don’t know how to find help?

“I’m really surprised, but there are people out there who not only don’t know we’re here, but that there’s a new law that protects them. I’m really surprised about the people who don’t know about the Rehab Act, just have no idea.

“There are youngsters who are in hospitals now who don’t realize that there are many things out there for them. Not just accessible curbs or jobs, but attitudes of people are now changing. So the disabled person is now beginning to realize that he can function on any level, on the same kinds of levels that everyone else functions on.

“When I was in the hospital, nobody told me that I was able to go to school, that I was able to get out in life and deal with individuals, that I was able to travel. I had no one come to me and say Larry, you can lead as normal a life, whatever that means, as anyone else can. All you’ve gotta do is just go for it.”

Larry’s been asked to do some public service television announcements aimed at getting disabled kids into Scouting. They want him to wear a Boy Scout uniform on camera. Would that embarrass him? “Are you kidding? No, I love it. Getting handicapped kids into Scouting? I love it.”

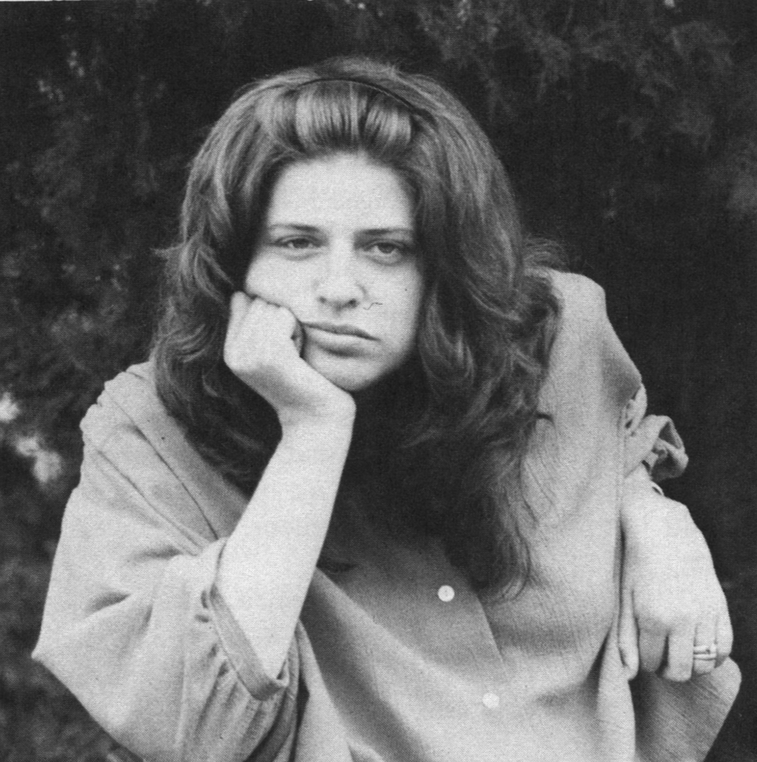

Syd Jacobs#

In 1974, a doctor friend asked me to drop in on a new patient of his who had broken her back in a mountaineering accident in the Cascade Range of Washington state. She had taken a fast slide down a snow slope and hit a rock. Her name was Syd Jacobs, she was 20 years old, she had a T6,7 break, looked kind of peaked and was pretty bummed out by the accident because she felt she’d done everything right and had her head in the right place just before the quick stop. What struck me was that her annoyance was over her performance, not her luck. The other thing that struck me as unusual was that, a few days after her accident, she was making plans about where and how she wanted to live and about what she wanted to do in life.

I next saw her in 1976, in Colorado, and it was clear that she had accomplished a lot of goals in a hurry. She had also become the first wheelchair jock I was to meet — light chair, no arm rests, one foot nonchalantly hooked over the web strap between her footrest supports and oozing vitality. She gave me my first inkling that I wasn’t cutting the raciest possible image in my chair.

Our next encounter was in Seattle, in 1978, and her world had expanded once again. She had just landed a job in a field she felt was perfect for her and which still gave her time off to train for her other life, about which more later. She still looked speedy and her health lit up her surroundings.

And now, in Boulder for a visit in 1979, she has some things to say.

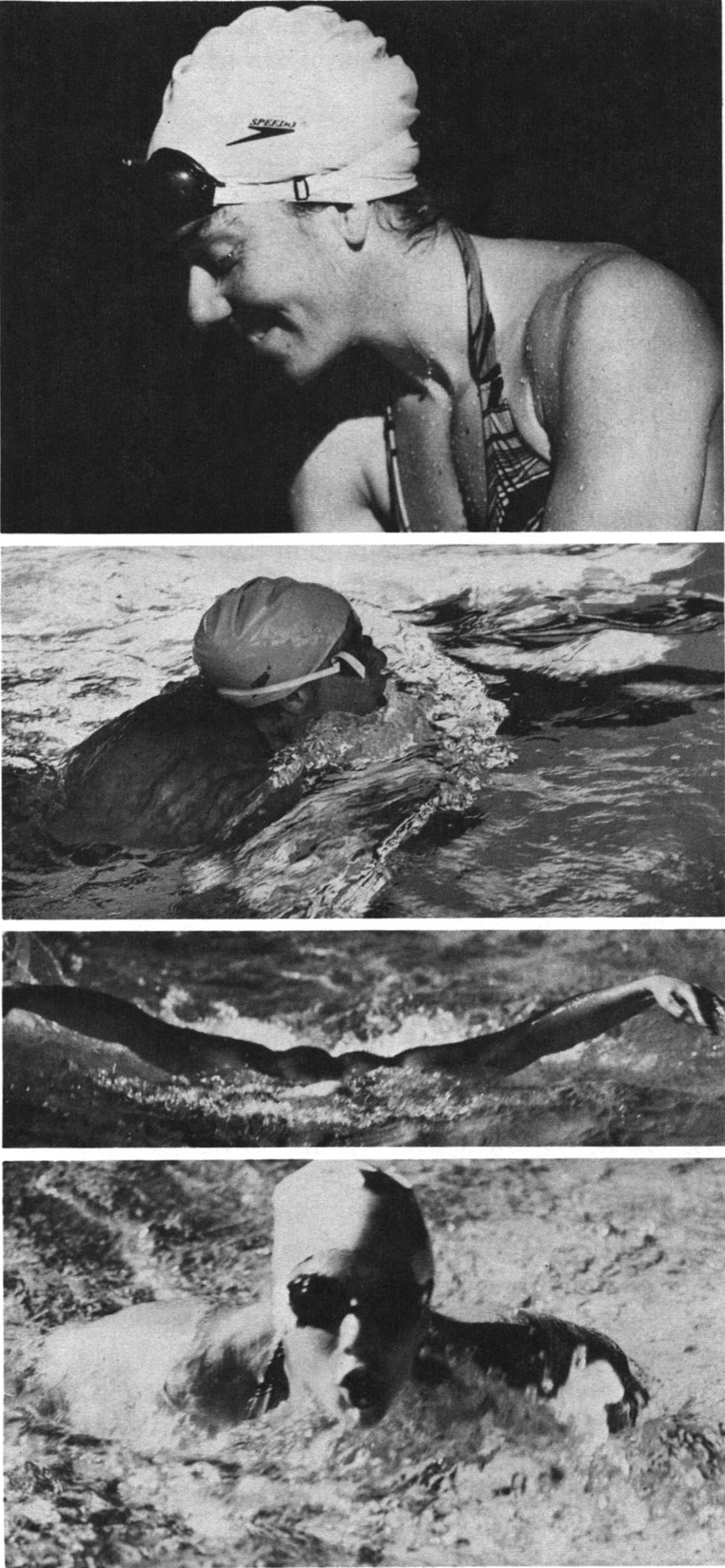

First, you should know that Syd was a competitive swimmer before her accident, which may or may not explain her dreams. They started in the hospital before she was even up in a chair.

“I had a lot of dreams about swimming. I would get in the water at one end of the pool and I’d be crippled, and I’d swim to the other end and I’d be able to get out and walk. As soon as I got up I started swimming, and I really liked it. I preferred swimming to lifting weights and pushing my chair around.”

“I got involved in wheelchair sports right away, and that really was a big influence because I met a lot of people that had been in wheelchairs for a long time and they helped me make a big adjustment — just watching people that were physically fit and could get around. That really helped.”

“I’ve been all over the country: Arizona, Virginia, New York, Kentucky, Colorado, everywhere; and in the world I’ve been to Brazil, England, Canada and Mexico; all competing for wheelchair sports. (She’s hoping to compete in swimming, perhaps in basketball, in the Netherlands in 1980.) That takes care of the competitive side of my life. I also like scuba diving and snorkeling, kayaking, sledding, skiing on a pulk, camping …” Syd gets around.

It didn’t all happen at once. Syd lived with her parents in Colorado for a few months, which was hard for her just because she had already been out and on her own. But: “Even before I got out of the hospital, my whole objective was to go back to Washington state, so the first opportunity I had I went up to see my friends for a week, and that’s when I decided I was definitely going back. So six months later, I moved back to Washington.”

The first thing Syd did back in Seattle was to finish off her BA in Communications, competing in wheelchair sports at the same time. Her vocational interests were a mixed bag: media communications on the one hand and environmental education on the other. Her new job may be a chance to do both.

She works for the National Park Service’s Visitor Information Service, which acts as a regional clearing house for outdoor recreation information. Next summer holds the promise of working at Rainier National Park as an interpretation trainee, an opportunity Syd values because it gets her back in the mountains and because she feels the job may eventually lead to producing brochures and films.

The most remarkable thing about her job is that a large government agency was flexible enough to give her time off for training and competition. “That was one of the stipulations when I took the job, that I was going to get time off when I wanted it. At least for the first year that I worked there. But they were looking for a disabled person in that job.”

How did she find the job? Through Handicapped Referral, an agency funded by CETA (Comprehensive Employment Training Act).

Syd dates actively and feels she’s too restless to settle down. Her most recent relationship ended when the man “decided I was too self-confident for him. He was afraid I was going to dominate his life, I guess. No one’s ever told me that before. (Laughs) I don’t think being a gimp had anything to do with it.”

About her chair: “The only time I really feel embarrassed about being in a wheelchair is when I act like a klutz. I think it’s a matter of self-confidence. If I feel confident and I can get around like anyone else, it doesn’t bother me a bit. Say, if I try to jump a curb and I miss, and all these people come rushing to the aid of the poor cripple on the street —that’s when I get embarrassed.

“If people are going to have a good perception of people in wheelchairs and disabled people in general, it’s up to us to make that perception good. And that’s by being pleasant and teaching people what we can and can’t do, instead of acting like we have a chip on our shoulder. If someone opens a door for me, fine. I’ll say thank you. But I’ll still open doors for other people too.

“I try to understand when people are trying to be helpful. If I’m pushing up a hill, got a rhythm going, I find it really aggravating when someone comes up behind me and just starts pushing me. It would be really easy to snap at them. I don’t need your help! But I think it’s really important to try to understand them. I think most people are pretty well-meaning, but you just have to be gentle with them —let ’em know.”

Syd lets ‘em know; she was with a basketball team on a plane to Edmonton when a steward referred to the team as wheelchair patients. Her response was outraged but still educational: “We’re not patients. We’re wheelchair athletes, do you mind?” She chuckles, and says she’s very seldom that nasty.

News flash: Syd didn’t get her summer job as a trainee at Rainier. She got something better, working as a naturalist at Hurricane Ridge in Olympic National Park and also as a researcher preparing a report on the accessibility of the park. Her daily duties include leading three 45-minute nature walks over decidedly hilly terrain, jaunts which have doubtless caused more than a few tourists to reassess their own physical prowess.

Lou Carello#

Lou lives on a quiet street in Fountain Valley, California. The house is neat, pleasant, unpretentious. He wants to know what we’re up to before he’ll talk, but he’s friendly. After he decides we’re OK, he’s very friendly.

Lou’s cultural background is Italian. He’s proud of it and it shows in his voice and mannerisms. He has intense eyes, a boxer’s quick moves and animated, mobile features. An actor’s face.

He is an actor. “I was in The Roy Campanella Story about two or three years ago, I had a very large part in Coming Home, Heroes, I did a Barnaby Jones, I’ve done a Paper Chase, I was in a TV movie called Some Kind of Miracle and I was part of a handicapped movie called A Different Approach. There’s a possibility of a movie in Boulder, Colorado, a very good part in that one, and the possibility of a TV series which would be based a lot on my life.”

And before that? “I didn’t graduate from high school. Got thrown out of school a couple of times, went to a reform school. I went through a system where they were more interested in disciplining me than teaching me.”

The Marine Corps got Lou off the streets and provided him with some of his first positive and reinforcing experiences. They also sent him to Vietnam, where he was shot. He’s a T9, with a lot of useful return. As a guess, he’s functionally about L4.

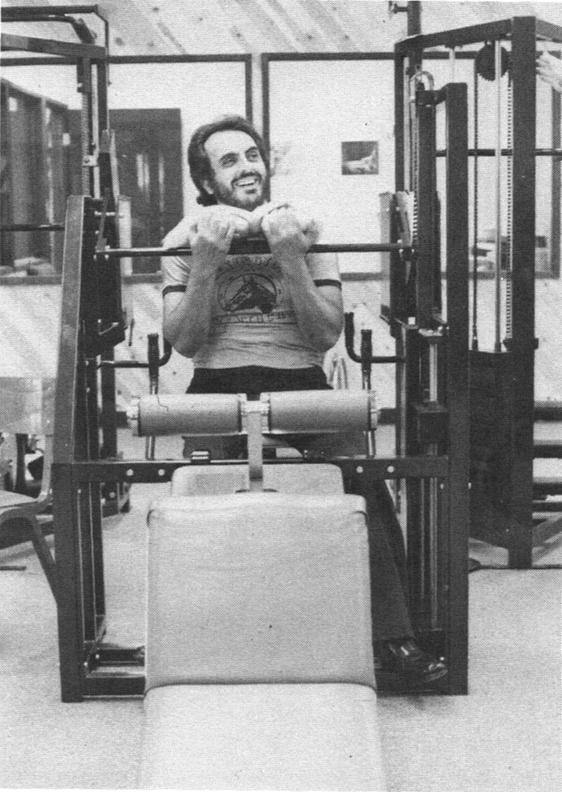

We continue our conversation at the local Nautilus Gym where Lou works out regularly. He likes what it does to his body and mind. He’d do a set of exercises, then talk. If he sounds breathless at times, he is.

What about after his rehabilitation? “I’m a former junkie. I wanted to work with narcotics addicts, but society says if you don’t have a piece of paper, you’re not qualified. And unfortunately, they wouldn’t take my real life experience.”

Then he got married. “I had the very fortunate thing of finding a woman I really loved about three and a half years ago. It’s kind of turned my life around. Things are going right for me, you know?”

How did the acting career happen? “I was at the VA Hospital one day, pushing down the hallway, and some guy says How’d you like to be in a movie? Why not? So I went down to his room and this guy gave me a piece of paper, I read a few words and they put it on tape, and about three months later I got a card in the mail telling me to go to Howard Johnson’s up in Hollywood. I’m always up for a little action, nothing to lose, so I go up there. And they hired me right on the spot. And that’s how I got into it. Nothing spectacular and no big plans to be a movie star. Just happened.”

Was working in Coming Home a satisfying experience for you? “It was a satisfying experience because of the way the director, Hal Ashby, handled it. The way he let it be done is that every day we would go there, a scene was rewritten. We’d go for it as to how we thought the scene might be done; not Hollywood style, but true style. And it made a big difference. A lot of the dialog was ad-libbed. The opening scene at the pool table was like, OK guys, we’re here, start talking about anything you want to pertaining to Vietnam. And we were able to do it.”

Lou sometimes feels discriminated against within the film industry, especially when walking people get handicapped roles he feels he’s qualified for: “I think what it is is that the public is not enough educated about people who are handicapped. The industry, being such a competitive industry, the man who’s directing cannot take the risk of having someone give a poor performance because his livelihood depends on it too. But there’s people like Hal Ashby or Jane Fonda, guys like Henry Winkler, Jon Voight; there’s enough of ’em out there that if you keep plugging you’re gonna get your breaks and eventually you’re gonna be there.”

Lou’s interest in educating the public is not only professional. He serves on the Governor’s Committee for the Hiring of the Handicapped, on the Executive Committee of the Wheelchair Basketball Association, and has a favorite vehicle of expression, which is through kids. He’s a Little League baseball coach, and just became an assistant coach for a Junior All American Football League team.

“I love kids. They react naturally to what they feel and what they see. And in communicating with them, because I’m at the same eye level that they are, it’s not Mr. Carello, it’s Lou. I’m their friend. I’m not this big guy that’s comin’ down on ’em, I’m somebody they can come up and put their arms around and hug and feel good. The bond is just beautiful.

“But the thing that’s really important is that by being around me, the handicapped person, they’re learning about handicapped people at such a young age where they themselves, as they grow up, this will be something they will already know and be able to deal with, and they’ll be able to pass the word along to their friends. So it’s a way of getting the word out. Because a guy’s in a wheelchair doesn’t mean he can’t coach us, doesn’t mean he can’t teach us. He’s able to do all these things.”

How has the injury changed your life? “I’ve become a softer person. I give more. I’ve become more in touch with my feelings. I’m more sensitive than I was before. I have more caring for people. I wake up every morning happy that I’m just waking up. And I’m sure that I have a different perspective on life because of my injury. So I live every day to the fullest that I can, and I’m happy just being here.”

Is there sex after paralysis? “Sure there is. Sex, to me, is for everybody —it all depends on how you do it. There’s love after injury. I think that’s more important than sex.”

Fred Rosene#

If software engineering can be said to have a pinnacle, Fred Rosene is there. He’s been with General Telephone and Electronics for 22 years, and can’t seem to shake success.

“When I started there, I decided one thing I didn’t want to be is a manager, and I’ve been a supervisor ever since one year after I got there. I move to get away from being a manager, and boom, no matter where I go, I end up as a manager. So I’m sort of resigned to becoming a manager.

“I’ve reached a point in my company that, whenever new projects come up, if I want them I can have them. A year and a half ago, I had four choices within one week that spread all the way from going to Italy to work, to going to Arizona to work, to working around here. I have offers all the time, so I really have total access to whatever I want to do within the corporation.”

Sound like a grim commitment to the work ethic? Read on.

Fred is the only paraplegic I know who was injured on a toboggan. It happened in 1951, when he was 19.

“I was sitting in the middle, because I thought that was the safest, and I had my feet up around the guy in front of me. We went down the hill, over a bump, and that did it. I suddenly thought, Gee, this is what it feels like to be paralyzed.”

He had nine more months to think about it at a Massachusetts hospital, where he experienced the minimal rehab common of the day. Then he went back to college. For a distinguished engineer, he took great pains to avoid becoming one: “My father went to RPI, and I did, and I didn’t like engineering. So I transferred to Tufts and ended up in engineering and didn’t like that either.” That was before his accident. Afterwards, he transferred to MIT because it was more accessible — there were two other wheelchair students there, which at that time was unique —and got his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mathematics.

He still wasn’t ready to be a working engineer, and in truth, I don’t really know when he actually did become one. I do know that he became director of his church youth program.

“We’d set up a drop-in program for kids who are sort of dropping out of everything else. It was a group of kids heavily involved in drugs and all sorts of juvenile delinquency. What happened was that I was able to relate to them because they had to help me as well as me helping them. They had to help me down the stairs and up the stairs, you know, and it kind of worked out that it wasn’t just a one-way thing. Really, I think I was better able to relate to them than if I’d been able bodied and walking around.

“Somebody asked me to coach the church basketball team. I didn’t know anything about coaching, really, but for some reason I said Yes, read a few books and I coached for 18 years. We ended up with a room full of trophies and we always ended up in the playoffs. We just had a good time. It was something it turned out I could do pretty well.” It’s interesting to note that one of Fred’s first players was Bruce Marquis, ex-Executive Director of the National Spinal Cord Injury Foundation. Bruce claims that Fred showed him that wheelers were not only as good as other people, but better. Hmm.

During this time, Fred had long since become an engineer and project manager for GTE. He had also gotten into the peace movement. Can you be an engineer for a corporation with significant defense contracts and be a peace-nik as well? Fred could. He moved to a division of his company that had no military ties, then led a group of adults and kids from his church to Washington to participate in the Death March and the Mass March which followed.

To fill the gaps in his spare time, Fred does such things as serving on a city committee to help make the city more accessible. For years, he’d avoided disability-related projects because “I realized that just because people were handicapped, it didn’t mean they had anything in common. I guess I reached a point where it didn’t bother me to be involved in a handicapped thing. I’d accepted my handicap to the point where I didn’t have to prove anything to anybody anymore.”

And now, after 28 years of paraplegia, of coaching, counseling, committees and conscience, has he had enough? Nope. There are two teenagers here now, waiting for Fred to finish the interview so they can do the grocery shopping for this weekend’s camping trip to Vermont. Fred’s leading it. Seventeen kids from his church.

And between his job and church and ancillary activities, surely there’s no time to spare?

“I’ve been fortunate enough to be able to make enough money to do basically what I want to do. I decided I wanted to skin dive, so I did that. I wanted to sail; I sail. I swim several times a week. I travel a lot.”

Have the 28 years ravaged his emotional and physical health? He admits to some depressed times during the early years, especially when he had to drop out of school to heal pressure sores. (This is an extremely common occurrence, and it’s very easy for the novice gimp to think that it’s always going to be this way. As almost everyone finds out, maintaining a cord-injured body is a learned skill that, once acquired, doesn’t depart.) Fred describes his outlook and health for the last 20-plus years as excellent, as they clearly are today.

His new project? A three-wheeled motorcycle. At the age of 47, Fred’s getting a dirt bike. For the hell of it. As he says, “There’s a wheelchair motorcycle club, believe it not.” Why not?

Nancy Becker Kennedy#

She’s mercurial in temperament, direct in demeanor and articulate as hell. Such a mouth, in fact, that this is a very easy profile to write. Nancy is so eminently quotable that she does it for me. Here’s a little prehistory in a nutshell, because Nancy’s going to take over right away. (Lest the foregoing makes her sound forbidding, she’s not. She’s warm, outgoing, witty, energetic and very funny. Just another Jewish girl running around in an electric wheelchair.)

1972. Nancy broke her neck diving when she was 20. C5,6. She did her rehabilitation, returned to college three weeks later, finished her BA, met her husband in graduate school, got her master’s in broadcast journalism and moved to Southern California when Steve was accepted to UCLA’s law school. She went to work in rehabilitation at Rancho los Amigos in Downey and he became a lawyer. It’s now Nancy’s ambition to get a job in broadcast news. That’s all.

I asked a really intelligent question to start things off, which dissolved Nancy into gales of laughter: Did your injury bum you out?

“No! It was like getting a bad bag of grapefruit at the grocery. It was nothing. I just sloughed it off and went back about my business! (Emotional about-face.) No, it was terribly depressing. I mean, the idea you’ll become a social leper is not that pleasant to deal with. It was such a feeling of shock, I was delirious for three weeks. That was my way of coping with it.”

After three weeks, she asked her doctor whether she’d walk again: “When he said No, I remember putting my hand to my mouth and staring out a window and thinking, How can a person hear this and not blow up? How can you hear such a horrible thing in the world, and not fall off?” But…

“There were good points for me, like when I noticed an orderly in the hospital who was better looking than he had to be. And he was paying a lot of attention to me, and I even noticed that he was responding to my personality, and that made me remember that I was still a person.

“I had a very insane group of friends. They had me shooting this movie, Deep Spoke, while I was still in the hospital. It was about a woman whose clitoris was misplaced in the spokes of her wheelchair and she finds it out while getting a shoeshine. So they didn’t make it easy for me to be depressed.”

There were ups and downs, and downs generated by her ups: “Sometimes I would just trash out and feel like a zero, and think, Wait a minute. If you’re being happy, it’s just because you’re not being realistic. Now get depressed again and get with it.” Up and down…

“I said to one friend, Do I look just like a person sitting in a chair? He says, Oh, you mean instead of a cripple? And I says Yeah! And he goes, You look like Patty Duke rehearsing a movie for being a quadriplegic. You don’t look like a real cripple. And I said, Oh thank goodness!”

Three weeks after she left the hospital, she was back in college: “Because I was thrust right back into what I was doing before, I was back on familiar ground. I was writing English papers again, I got my personality and wit back, and I functionally became very good because I had to type, I had to phone, I had to get things through for school.” (She writes elegantly and fast, holding the pen vertically in the hinge of her hand. No splints.)

“So one big thing is to get back to doing things real quick, and the other is to be crazy enough not to lower your expectations one bit because you’re in a wheelchair. I had this psychologist who told me: Love will have to mean less to you, religion will have to mean more to you, and work will have to take on a greater significance in your life. And I asked, What about falling in love? He said, Well, you’ll have to direct your energies into other things. I said, Look, you’re asking me to play probabilities because of my wheelchair. When you were in high school, somebody could have said, Look, you’re skinny, you’re not very goodlooking, you’ll probably get married to a woman you don’t think is pretty enough, and you’ll be very unhappy. But you did a different thing. You became a psychologist and you wear suede jackets and you’re real happy. You turned things to your advantage and I can turn things to mine.

“I wanted the same excitement out of life; I wanted an exciting career, I wanted to be in love, and, even though all indicators said I should forget it, I didn’t. And it did happen.”

So why, with a journalism background, did she go into rehabilitation work?

“The first thing I had a great compulsion to do was to get to newly injured people and tell them, It’s not what you think. Because I really, when I was first injured, thought everything was all over. And my biggest fear was that I’d be socially ostracized. I kind of was carrying my prejudices against people in wheelchairs into my disability. And when I found out that I could resume my life and have as much pleasure, if not more, than I had before my injury, I felt a great need to get to newly injured people and tell them that.”

Why, then, does she want to go into news? “I was an activist with concerns in all kinds of areas before my injury. I was active in the women’s movement, the grape boycott, the abortion movement —I was even a socialist. I left some of these things behind, but I was basically just concerned with things being fair. So my desires for social justice are not just related to disability. I felt that news would satisfy me because I had 20 years of desires that pre-dated my accident that were not being dealt with by only doing disability-related work.”

So far, she’s produced a 28-minute film, Wallflower: the Disabled in Society, and has appeared —with extremely positive effect —on a segment of Sixty Minutes dealing with work disincentives. She’s applied to two local stations, has been given encouragement, but so far, no job.

Nancy’s marriage is obviously very precious to her. She starts to talk about Steve, marriage, in-laws; she’s alive with enthusiasm and love and compliments, then she backs off because some things are to be experienced rather than spoken of. She’s an irreverent woman, is Nancy, but some things command reverence.

Parting shot, for the librarian: “Some people don’t believe in themselves for various reasons, and they think that the fun things in life are for somebody else. Nobody out there is any less of an asshole than you are. You can want everything they want. You know, don’t feel insecure.”

Such a mouth.

News flash: Nancy just got her job as associate producer at KCET News.