Lives VI#

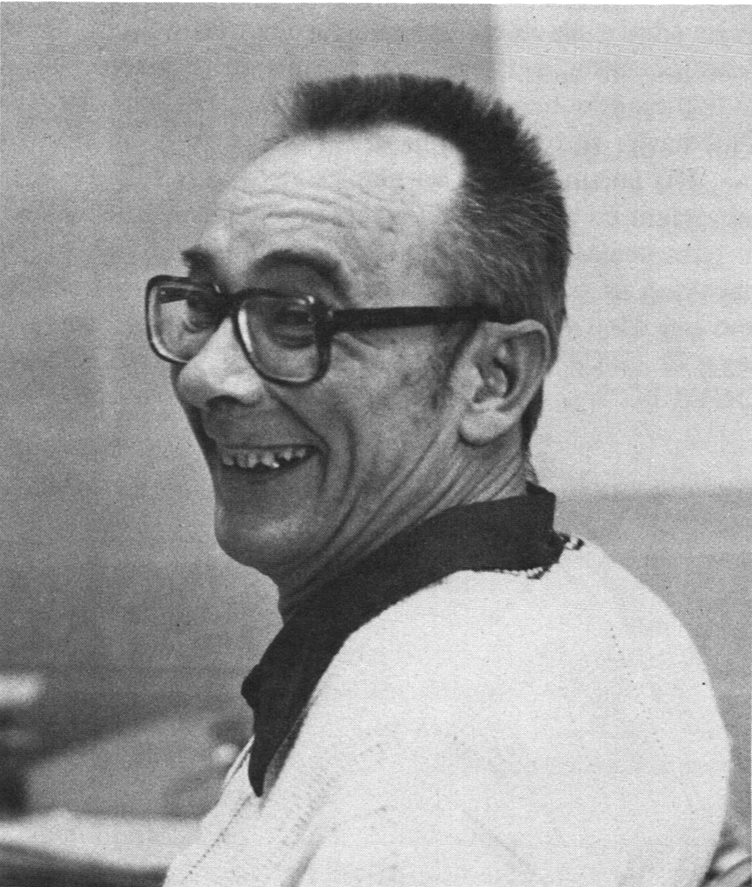

Tom Deniston#

There’s a certain irony in his accident. He’d been a pilot in Vietnam for two years, put in 2,000 hours of combat time, had lost two airplanes and had walked away from both of them without a scratch. Then, one day, while he was leaning on a porch railing jawing with some friends, the railing collapsed and he fell 12 feet. He’s a C5,6 and doesn’t think highly of porches prefabricated by the lowest bidder. That was 1969, a week before his thirty-first birthday.

In 1969, Tom had a college education, a passion for flying, a wife and three boys. He had decided early on what he wanted from his occupation: “I wanted a job I could enjoy and I wanted to be able to help other people. And from that came the idea that I should go into the Air Force.” And from that came eight or nine expense-paid trips around the world, a broken neck, a rehabilitation at Fitzsimmons in Denver followed by more at the Memphis VA Hospital, a job for two years with a large envelope company and the realization that he has a knack for changing people around to his point of view. That led him into advocacy work for the disabled, which brought him to the attention of the Paralyzed Veterans of America, whose vice-president he soon became. After two elective terms with PVA, he moved to Albuquerque to attend graduate school at the University of New Mexico, but dropped higher education in a flash when PVA decided to set up a pilot advocacy program in Albuquerque. Tom’s now Advocacy Director for the Southwest Region of PVA, about which more later.

Tom’s first job at the envelope company satisfied one of his major concerns, which was to prove to himself that he could rejoin the work force. He had two other burning concerns: flying and sex, in that order.

“My neurosurgeon came wandering in, and I’ve got a question. I want to know when am I gonna get back to the cockpit? When can I go flying again? And his comment to me was something along the line of, Oh, you broke your neck. You’re gonna be paralyzed from the shoulders down. Don’t worry about it. You can go home and eat and sleep and watch TV and talk and enjoy life and collect your benefits. Tom feels that this attitude represented, say, a limited outlook.

Yet nobody at the hospitals could tell him anything about flying, until one day an old injury told him that you can fly an airplane with hand controls. “Well that solved that problem.”

Then, he asked his urologist about sexual function, who told him “It’s a little too early to tell.” He persisted in asking his nasty little question, and got shunted from referral doctor to urologist to social worker to psychologist and back, and got no answers.

“I got lucky. In the Memphis VA, the medical doctor in charge of the outpatient clinic was a quadriplegic himself. He’d not only worked in SCI, but he’d been one and was more than willing to answer any questions you had. And the guy had answers. I got more solutions — suggestions and ideas on how to remedy a questionable sex life—from people who’d been injured for 10 years or more than I did from the whole of the medical profession.

“We had a lot of problems, the wife and I did, initially. It took some getting used to and it took some changes of attitudes. My conception of sexuality may not be totally reversed, now that I’m injured, but it’s considerably different. The male ego used, to me, to be the thing that everyone seemed to think you were trying to take care of. And that’s not where it all is. Sexuality has to be a sharing thing, and it has to be a pair of egos satisfied simultaneously.

“A young fellow was injured recently, and it just hurt so badly to see him lying there saying, I’m half a man now. That’s it. That ruins it. I am no more a person. And that’s just so terribly wrong! If you can be the sharing, concerned, empathetic individual, the two of you work out an arrangement where both of you are not only comfortable, but satisfied and pleased with the whole situation. You’ve reinforced your partner who in turn is gonna be more anxious to reinforce you, which, in my estimation, makes you a better person than the macho bull that you were to begin with.”

About his kids, now teenagers and young adults: “You can go to movies together, you can go to ball games together, you can do a lot of things and still get the comradeship, the father-son relationship, without having to go out and make a major production of climbing the Matterhorn with your son at your side.”

A few sidelines — He’s active in Handicapped Scouting, lectures to medical students about disability and sexual function, does a Sunday radio talk show, bowls regularly and travels a lot, both on the job and off.

He credits his unusually good arm and hand function —“I’d arm wrestle anybody for a beer in any bar in town” —to his determination to get strong enough to throw the neurosurgeon of limited outlook out of the armed forces. As a matter of fact, he attributes everything good to determination, and to see Tom Deniston’s determination in action, the thing to do is roll into the Southwest Regional Office of PVA.

The place is a former service station, ramped, panelled and converted to office and meeting space. Several friendly people in chairs are moving about, stacking literature, answering a constant clamor of telephones and coffeeing up. In the main office, I hear snatches of phone conversations:

Are you talking about the Section H Subsidy?

That’s preferential treatment! Do it for one, do it for all.

You think that’s a barrier? How about…

This place means business. I roll around a partition and find Tom on the phone, so I look around and listen. There’s a small American flag on his desk, and stacks of legal books, books on barrier-free design, the SCI Manual, HUD manuals —tools of his trade.

Right now he’s talking to a newspaper reporter about the very hot issue of accessible transit: “The price of the lift is $14,000, and they’re talking about $20,000 now, which is a bald-faced bug-eyed crooked-tongued rip-off. Those boys are trying to make up the inflationary cost of bus prices on those lifts.”

Tom’s a politician, a patent medicine huckster, one of those folksy types who can wrap spider webs of logic, charm, persuasion and pugnacity around any discussion. On the subject of a recent meeting held to discuss making city council meetings accessible, when all attending wheelers were hauled up a flight of stairs to the meeting room by firemen rather than meeting in the already accessible library downstairs, Tom explains to the reporter: “The mayor’s a chain smoker, and he wasn’t willing to abdicate his right to smoke.” End of communication. Tom turns to me, grins mischievously: “Medivac and advanced medical care have made me a terrible pain in the mayor’s side.”

Hot tip: “I think the first thing a person oughta do is get out of that damn hospital environment, because it’ll kill you. They’re going to treat you as a disabled person and the longer you stay there, the more reliant you become, the thicker that umbilical cord becomes and suddenly you can’t get out. Initially, the philosophy for SCI’s was: Oh poor dear, he’s not gonna live long. So let him live fast, love hard, die young and leave a beautiful memory. He could get away with anything, but he didn’t get very far from the hospital.”

He feels that there are still what he calls Hospital Homesteaders: “They never leave the hospital. They couldn’t. They’re frightened to death that if that bed was not available for them, they would have to go outside that door into the big, mean, ugly world. And if you let the hospital environment stay with you long enough, it’ll do that to you.”

So Tom Deniston has flown his airplane again and cemented his family bonds. As for his occupational objectives: “By having that injury, I found not only a job that I enjoy doing, but I’m also helping people. At least I think I am, as an advocate for handicapped people. (He lightens up a little, smiles wistfully) It’s a shame I had to break my neck to do it…”

Frank Musinsky#

Yale, BA in English literature and history, copy boy for the New York Times, playwright, dialog director for Universal Studios, independent producer in Hollywood and overseas, and, as a refugee from television’s rearrangement of the motion picture industry, the head of marketing for five shoe factories. He has a gracious wife, Bonny, three children and a beautiful home in Weston, a suburb of Boston. In 1971, Frank was 40 years old.

That year, when Hurricane Doria was stomping the eastern seaboard, Frank was out driving his VW on the Mass Pike. A capricious gust of wind flipped him. T6,7. Local hospital, immediate laminectomy; survived a pulmonary embolism, transferred to Boston University (Regional SCI Center) “and learned what it’s all about.”

One of the things he apparently knew innately, something that several people in these pages have suggested, was to get back as quickly as possible to what he was doing before.

At his request, he was moved to the Extended Care Unit so that he could become independent of the help of nurses and aides and get back to work. He wanted to know if he could still manage. He’d catch a cab every morning, go to his office, get carried up a flight of stairs and return to ECU at the end of the day.

What he found at work is what he knew all along; he couldn’t do the amount of traveling required by his old job. So he applied to a different division of his company (SCOA Industries, now a mini-conglomerate) and was hired as an advertising executive for Hill’s Department Stores, a SCOA-owned chain which has grown from 30 to 80 stores during Frank’s tenure there. He likes his company and he likes the work. “I’m the only person in a wheelchair working for the company, and we employ 12,000 people. I don’t consider that to be bending over backwards on behalf of the disabled …” But they’ve treated him well.

While he was still in the hospital, and with the help of the Massachusetts Rehabilitation Commission, his house was ramped and made otherwise accessible. How was it, coming home?

“Superficially, very easy. My wife is an extraordinary woman from the standpoint of the wide spectrum of patience that she has and the tremendously mature and open-hearted responses that she has to people. Not just to me. So there was never any problem in our marriage.” Superficially, it seems, because the three kids had a hard time dealing with Dad being in a chair. They didn’t want to hear or talk about it, and their son tended to deny the injury emotionally. “He would still very much like me not to be in the chair.” Frank and Bonny see time and maturity as the best cures. The discussion did bring out this advice.

“Anyone who’s newly injured, who’s going to go out in the world, should not think that everything is a bed of roses, because that isn’t true. You can accomplish an awful lot. You can’t accomplish everything. There will be stumbling blocks that you will get over through getting involved in other things, getting outside of yourself. Then there are other hurdles that you don’t think you can jump over, and you’re going to be very surprised that, God —you get out there and it’s nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

How about other disabled people? “For the first year after my accident I found myself avoiding contact with other people in wheelchairs. As I look back upon it, I was looking at my other self. I was seeing what other people looked like in chairs, and I didn’t like the look. And because I didn’t like the look, I wanted to avoid it. What I learned, however, is that it really didn’t matter how I perceived what they look like, it mattered how able bodied people perceive them. I saw that they felt quite natural with people in wheelchairs. Why shouldn’t I, in a wheelchair, feel equally natural? And gradually the barriers came down.”

Now: “I think it’s important to spend time with other people in wheelchairs so that one doesn’t feel completely disaffected with oneself. If you’re only around people who are able bodied, you may, over a period of time, actually think there’s something wrong with you. And there is nothing wrong with you. I don’t say that you have a mission in life to spend time only with people who are disabled. That’s as ridiculous as spending no time.”

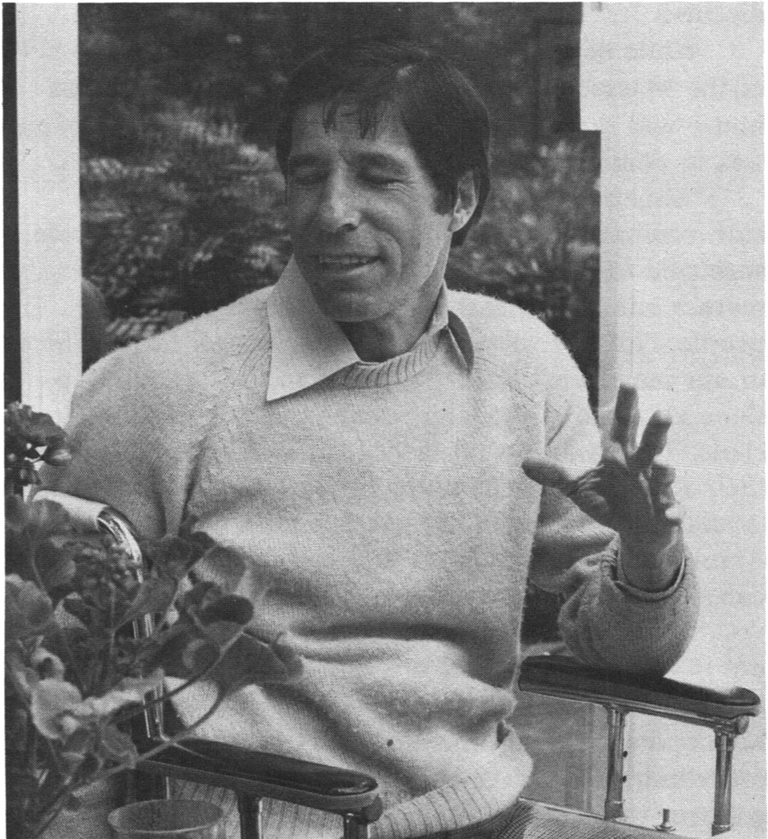

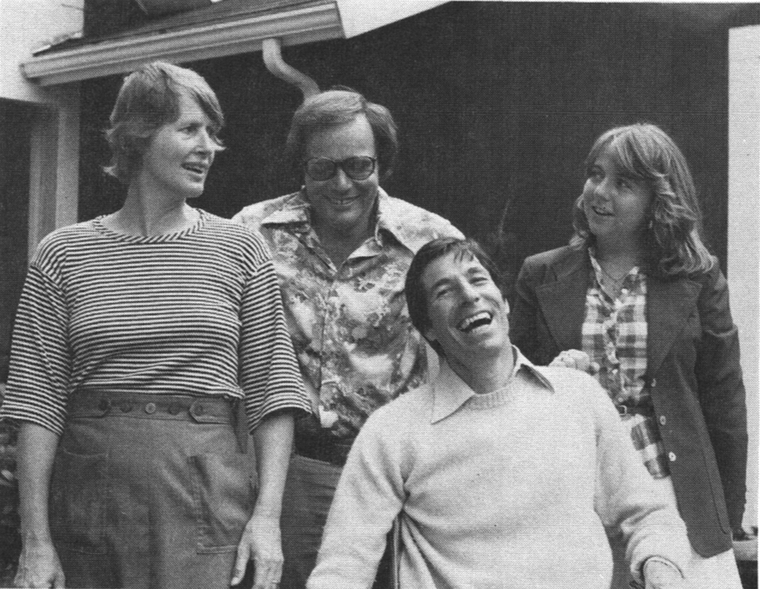

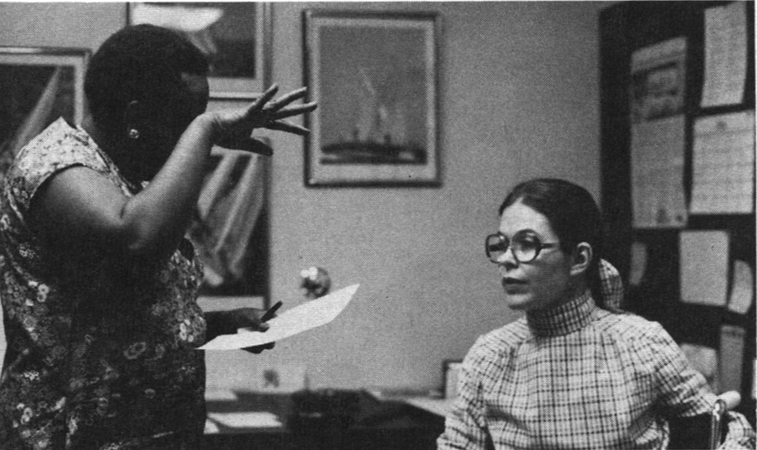

Here’s Frank being non-discriminatory in his relationships. Bonny, his wife, has a cast on her broken leg. Bruce Marquis, Executive Director of NSCIF, is on crutches and has a cast on his torn Achilles’ tendon. Barbara Langdon, on the right, is temporarily able bodied.

More advice: “Develop a relationship with at least one person you trust to the extent that whatever has happened to you has absolutely no relevance in your relationship.” And: “Whether you’re a male or a female, get yourself into bed with someone of the opposite sex, or even of the same sex as far as I’m concerned, as quickly as you possibly can.”

Hot tip: “Don’t do what I always do, which is to put the chair arm on the roof, get into the car, take off and lose the arm. Thirty-five dollars an arm. Be careful.” What kind of arms do you buy? “Generally, Schwarzenegger arms.”

Ed Eckenhoff#

The Midwestern Regional SCI Unit is at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago and Northwestern Memorial Hospital. Like most of this country’s premiere rehabilitation establishments, RIC had humble beginnings in an old warehouse that nobody else wanted. Today, it’s a soaring glass and steel tower standing between Lake Michigan and the hospital.

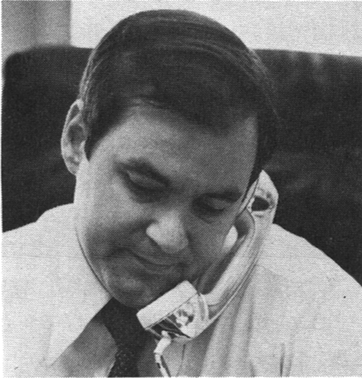

On the fifteenth floor, we’re talking to Ed Eckenhoff, Vice President and Administrator of RIC. Once the camera, recorder and lights are on, I open with this splendid icebreaker:

What do you do for a living? (Good crisp, to-the-point question.)

“I run a hospital.” (Good crisp, to-the-point answer.)

That’s ridiculous. Why would a gimp run a hospital? (Loosen it up, give him something to respond to.)

“I beg your pardon?” (Ooops.)

Why would a gimp run a hospital? (Bravely, brazenly, I repeat.)

“Why would a what?”

A gimp.

“A gimp. What’s that?”

Cut.

So it was that Ed Eckenhoff, Administrator of RIC, auto wreck survivor, T11 paraplegic for 16 years, first heard that word. It was, to be sure, the only gap in his knowledge to be found. In his job he’s responsible for over 30 departments and 700 employees of the largest comprehensive rehabilitation facility in the country. He knows a lot about gimps.

As he sits behind his desk in a conventional swivel chair, one is hard put to discover a disability. No wheelchair. Except for the vasty corridors of O’Hare Airport, he has always used braces and crutches to get where he’s going. Why braces?

“I like to walk. I like athletics. I’ve always been very active — playing football, tennis, swimming, skiing — so to a certain extent, this was just another sport; something I had to win at. And I like to win.

“I like to be as tall as I can. I can still be boisterous, yell, rant and rave, knock doors down— yeah, and get knocked over—and I like to be physically tired at times. So I walk.”

He walked from his rehabilitation at the University of Pennsylvania back to college after missing only one semester. How was it? How about dating?

“I thought I was going to be very limited. That’s what happens when you’re recuperating and you’re thinking the worst and you’re always tending to be a bit negative and not giving yourself enough credit. I thought I’d have a lot of problems. I am not going to tell you how well I fared, unless you promise not to tell my mother.” (Ed hastens to point out that he no longer dates. He’s been happily married for a year.)

President of his fraternity, vice president of his senior class, he left with a master’s degree in psychology. After four years of counseling in a large school system, he dropped everything, went to Washington University in Saint Louis and emerged with a degree in health care administration. That led to a residency at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and thence to RIC.

Ed emphasizes the fact that he came from a very competitive, achievement-oriented environment. His father, for example, is dean of a large medical school, one brother is an architect, another is a physician and the third is a biochemist. Yet what strikes me is that the entire world is Ed’s apple by virtue of the fact that he thinks it is.

“I’ve been in a couple of different professional fields; who knows where I’ll be in five years? Hobbies have taken me in various directions — furniture making, collecting eighteenth century furniture and art, which makes you wonder, Jeez, maybe he’d like to become a curator some day, and there’s no reason why I couldn’t do that. I played the piano for 14, 15 years and there is no reason why, if I had practiced six hours a day, I couldn’t have been a concert pianist. I’ve done a lot of different things and that’s, I suppose, why I’m not too terribly depressed or upset about my disability. There’s just a hell of a lot of options.

“Rarely, unless you’re in sports, is a physical disability going to impair what you can do. We strain a little bit more, we have to be a bit more competitive, we have to sell ourselves a bit better; but I’ve had no problem in doing that and I would like to think that most people would have no problem in doing that.

“Your potential is guided by your outlook on life. It’s simple!” Yup.

Buzz Hicks#

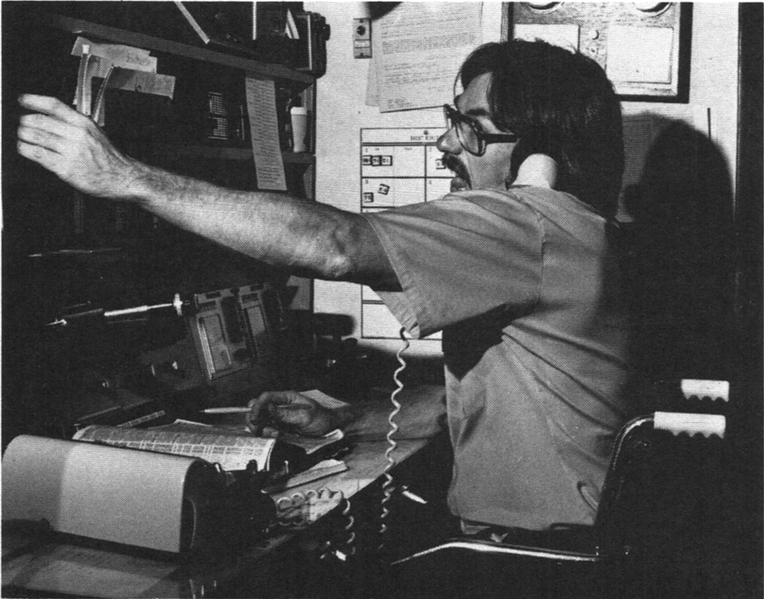

A young man is alone in a dispatching room designed to accommodate only two situations, sheer boredom and dire emergency. At one end are an easy chair, a color television and a microwave oven. At the other end are radio console, CB scanner, paging system, city and county maps, files of location cards and a telephone. In Buzz Hicks’ case, there’s also a Bible.

Buzz: Engine 2; dispatch.

(Radio: blat, bleep, scratch, burp — Engine 2 acknowledges)

Buzz: Chief one has been notified.

(Radio: Roger.) (Phone rings)

Buzz: Fire emergency. Yes ma’am … What’s your address? 361 Magnolia. Your drapes in the front room. What’s your phone number, ma’am? Your phone number. 482-1131. OK, we’ll get someone there right away.

(Consults location cards, then punches buttons on console.)

Buzz: Engine 4, truck 1, squad 1 —361 Magnolia. Drapes on fire. Group 2913. (Phone rings)

Buzz: Fort Collins Fire Department. Yeah.

Yes. We’ve got gas leaking in a sewer system at Campus West. Can you hold on a second?

(To radio)

Engine 2, dispatch. I’m unable to find

Bureau 2, Bureau 3 is on the line. He’s willing to come out there.

(Blat, bleep, static of radio responding.)

Buzz: Roger. 17:25.

Buzz has a lot of responsibility, not too removed from that of an air traffic controller. He is a dispatcher for eight fire stations and all emergency health vehicles in a 250 square mile area. Daily, or nightly, he contributes directly to the welfare and safety of the city of Fort Collins and its satellite towns. At the end of his 12 hour shift, he wheels to his Volvo and drives home. He has the air of a man who likes his job but is now heading back to the important part of his life.

In 1971, Buzz had a high school diploma and a bunch of problems. He was depressed, a self-acknowledged doper and freak, and things were not going at all well. He and a friend had aborted a trip to Central America after rolling their car, and they were hitch hiking home. As he was walking along a highway near San Antonio, his back to the traffic, he was hit by a car. He’s a T3.

Buzz had a desperate time finding this job. “I just went into the Fire Department to talk to the chief, and he thought I could do it and I thought I could do it, and they took the ad out of the paper and I got hired.” That’s all. His formal education still stops with high school, although since his accident he has taken a personal tax course and augments his living by consulting.

For recreation, he drives a lot, rides his Centauri (an arm-powered trike), fishes and occasionally works out in a local gym. He has canoed on flat water and has dumped, which probably means he swims. He plays guitar with a band of friends.

He has been married and divorced since his accident, and doesn’t really know why it didn’t work out. He says he would remarry, “but not just to fill a void in my life.” He now lives with two roommates in a rented home and seems extremely healthy and happy. You can see it in his body, his eyes and what he says. And it’s not at all difficult to find out what makes him that way.

Buzz joined what he calls a “fellowship of Christian believers who’ve been looking towards a committed life together, living out our lives as a family.” It has become a life that he wouldn’t and couldn’t give up, and it is obvious that his entire sense of completeness issues from this group and this lifestyle. On Buzz, it sits well: “It’s something I’ve been brought into by the Lord, and He’s really changed my heart and my mind about a lot of things —and that is being committed to other people and living my life out for other people.”

Now when I hear someone talk that easily about the Lord, I usually keep one hand on my wallet. Not so with Buzz. He’s got a light, a Lord and a true extended family. I envy him. I envy him and his ability to say these things:

“I think we can look way above it and look out of ourselves and look at other people and try to focus our love towards them instead of trying to establish our own selves. I think in loving others, we then become grounded. Grounded in love.

“I think it’s easy for us to get ourselves focussed on where we’re at instead of where we can be at in other people’s lives.

“I’m seeing now that I really must function in my wheelchair, in society. I think this will get us out of the dependency upon our handicaps and start depending on the life and the love that’s around us.”

There’s a lot of life and love around Buzz. You can see it when he comes in for another 12 hour shift (four days on, four days off). His co-workers are drawn to him, want to know what he’s been doing on his days off. There’s the normal horseplay that exists wherever men are bored because they are waiting to be scared by the next emergency, but the usual profanity is missing. Does the Bible Buzz carries really negate the working man’s God-given right to use His name in vain?

Buzz doesn’t preach. These men are not members of his Fellowship. Or are they? In a very broad sense, they must feel that they are.

Cliff Crase#

This profile is a quickie, partly because Cliff is already well known, and partly because I caught him just before the deadline of one of the magazines he edits and he understandably couldn’t spare me a lot of time.

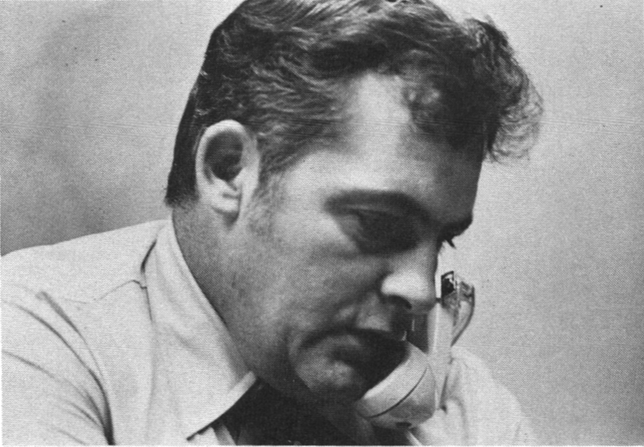

Cliff’s accident was in 1959, a sports car wreck while returning to his air base in Minnesota. He was 21 years old. C6,7. He’s a quiet-spoken man who still feels sports to be near the core of his existence, a fact which shows in his massive upper body and craggy features.

After rehabilitation, and after a couple of years in his native upper Michigan, he went to the University of Illinois, took a lot of business courses and a few in advertising, got his degree and became a stock broker.

But before he left the University, he got hooked on wheelchair sports. He’d been an all-state basketball player, had played a lot in the Air Force, so sports were very important to him. Since quads normally don’t get to play much in wheelchair basketball games, he got on the swimming and track teams which in turn provided his ticket to the National Games.

So, as the stock brokerage game changed through the years, becoming centralized in four or five corporations, Cliff just leaned with the wind and concentrated on analyzing and consulting. During the same years, he qualified for 10 different US teams that went all over the world. He specialized in pentathlon, did a lot of winning and a lot of traveling.

In 1969, he married Nancy. That was the year he started writing a monthly wheelchair sports section for Paraplegia News, a magazine owned by the Paralyzed Veterans of America. He also became Sports Coordinator for PVA and served on its Investments Committee. He still hold both posts.

In 1975, he and Nancy started their own magazine, Sports ’n Spokes, as a back room operation. It’s a front room operation now, but it doesn’t look like the Washington Post’s newsroom. It’s a small magazine targeted at the jock minority within the handicapped minority.

In 1978, Cliff’s close friend and long-time editor of Paraplegia News, Bob Webb, died. Cliff flew out to Los Angeles to deliver the eulogy, and didn’t give the magazine another thought until he was suddenly drafted as its editor. So now Cliff and Nancy have two deadlines instead of one, two magazines to put to bed, 28,000 readers to satisfy and I can’t understand why Cliff hasn’t thrown me out of his office yet.

His parting words let you know what’s still important to him: “Paraplegics, or the parents or wives of paraplegics, can’t picture someone scuba diving or kayaking or marathoning like they do, and they write in and say That’s totally impossible. And the magazine says, IT ISN’T TOTALLY IMPOSSIBLE. JOE BLOW DOES IT!”

Don Rugg#

1954. Don was newly married and had just graduated with a degree in electrical engineering from Denver University. Car wreck. C5. Poor timing, personally and historically, because medicine’s ability to deal with quadriplegia wasn’t too finely honed in 1954.

Don spent a year at a general hospital cooking up pressure sores, then a half year healing them at Colorado General in Denver. By 1956, he could still only sit for four hours at a maximum because his skin wouldn’t tolerate longer periods and he didn’t have the upper body strength to shift his weight. This was disturbing, to say the least, and nobody had any idea how to overcome the problem.

Except Don. Like many others in this book, he found the answers within himself because they didn’t exist anywhere else. Necessity is the mother of invention, and Don started visualizing in his mind an electric wheelchair that could shift his weight for him. He teamed up with a friend, a mechanical engineer, who produced and assembled the parts. He was strongly encouraged by his doctor at Colorado General, a maverick named John Young who went on to start Craig Hospital and later brought enlightened SCI care to Good Samaritan Hospital in Phoenix. After months of stop-and-go frustrations, Don had his first reclining electric wheelchair.

“It was one of those things that worked out far better than what one might expect it to in the beginning, because from that time on I haven’t been hospitalized once with a pressure sore. Without the reclining chair, I had to be moved physically from the wheelchair and laid down about every four hours. Now I can stay in the chair for 16 hours a day. It’s allowed me to work full-time, where before I had to work half-time.”

During those early years, did he ever want to give up and quit? “Whenever you end up a quadriplegic, it’s very difficult to say OK, I’m not going to do anything, because at that point there’s not a damn thing you can do anyway. I was not doing anything to give up! But I also was not very content with doing nothing. I think there is an adjustment period there after you do nothing for an extended period of time. You realize that it is not a viable alternative to living.

“When you lose so much physical use of your body, it does really destroy one’s self-image. There’s no getting around that. And it also destroys one’s self-confidence. At this time it’s really crucial for the people around you to help restore that. And then after it once starts coming back, then it’s a snowballing effect. As you start gaining more self-confidence, then your interaction with the people around you becomes more positive, which reinforces it.”

Snowballing: By 1958, he had his master’s and a part-time job at the Denver Research Institute (the research arm of DU). By 1960, he was working full-time and handling three additional hours of night classes. By 1968, he had his doctorate. How did he get all this education? Was he rich?

“No! I’m a farmer. I came to Denver on a scholarship, I got my master’s degree through the Department of Vocational Rehabilitation, and I got my PhD through the fringe benefits of working at the University of Denver.”

His vocational interest is in the propagation of very low frequency waves, and his work is mainly the analysis and theoretical review of data and the consequent design of devices based on theory. How does he handle lab work?

“Whenever I’m in the lab, it’s usually directing an experimental set-up, having the technician take the data. I am limited in doing some of the lab work that the other engineers do for themselves, but this is no fundamental limitation on what I can do, what I can achieve.”

More on support: “I think anyone with a severe disability, that their accomplishments are largely affected by the attitudes of the people around them. I’ve been really fortunate in having a wife that was always supportive and understanding and did not take anything less than a maximum effort out of me. She also did not take the attitude that it was her duty, and her sole duty, to take care of me for the rest of my life.”

Here’s a quarter century of marriage and a quarter century of SCI. Any comment?

“I honestly believe that a SCI has never helped any marriage, any more than it helps in any other thing. It’d be a heck of a lot easier to do without the SCI. So I’ve never been one to say I’m blessed because I got my neck broke. The problems that arise —there are problems as in any marriage —they’re different. We have, by luck or somehow, worked out the problems.”

Don is saddened by people who wait around for a cure. But what if there were one? “If there’s a miracle cure that comes along, then fine. A lot of my problems will be over. And probably a lot of new ones would creep in.” Jeez, just think of the trauma of dealing with an able body after all these years. “Right! But I figure that if I can handle the situation as it exists today, I could damn sure handle it if I suddenly was not paralyzed.”

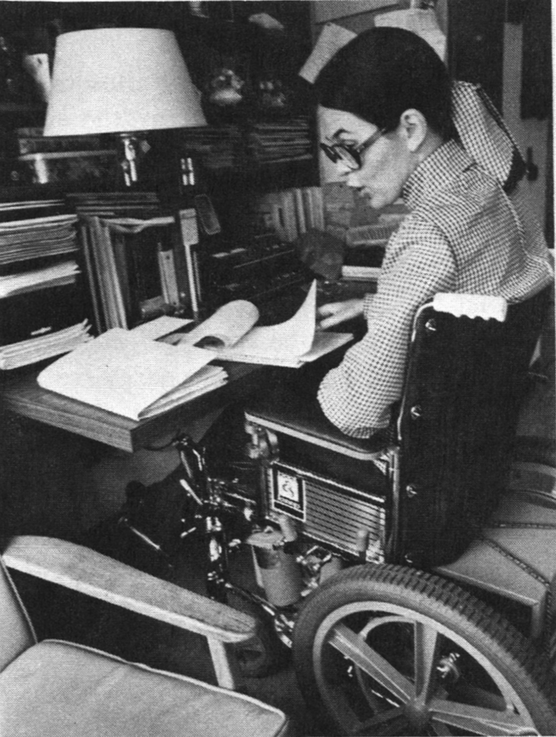

Judy Gilliom#

Remember those science fiction movies and books about a central intelligence which ran the entire show in its part of the universe? It was a being that could juggle quarks and quasars and anti-matter and black holes without moving a motor neuron. Sometimes it was depicted as a gyroscopically swivelling eye or sometimes as a container full of pulsing protoplasm. This intelligence needed no arms and legs because all the events it initiated were mind and energy transactions. If you’re in the central intelligence game, CIA excluded, you get things done by creating and manipulating energy patterns.

Judy doesn’t swivel or pulse. She’ll be the first to tell you she does nothing. But somehow, she gets things done with astounding efficiency. Of all the people in this book, Judy has the least physical function left to her. Of all the people in this book, none is more functional.

One of the things central intelligences apparently aren’t supposed to do is housework. In 1970, Judy fell from a kitchen counter while cleaning cabinets. C4,5. Bad mistake. She was 26, managing editor of a magazine, and knew she had no business cleaning kitchen cabinets.

She stayed three months in acute care, surviving against predictions, then spent eight months at one of the country’s best known rehab centers. It shall remain nameless, lest I slander an institution that has done well for many of us, yet Judy’s observations are pertinent to anyone associated with rehabilitation work.

“Those who are injured when they are adolescents and don’t really have formed personalities when they go there are able to deal with the kind of condescending, dictatorial, pushing and shoving approach they take there. Whereas people who are pretty much adults at the time they arrive find it more debilitating than the injury. That was the experience I had.”

Mostly, she couldn’t understand why the Very Famous Medical Director was always off in Amsterdam or Sydney giving speeches about paralysis and human dignity, while back on the home front she was getting bad advice and pressure sores.

The advice she got, basically, was to learn to type with sticks and slings and pulleys. An engineer-friend took one look at the equipment she’d been sent home with and advised her to get rid of it all and hire a person. So began her credo on adaptive devices:

“The fewer you have, the better off you are. Junk, basically, gets in your way. If it’s wires, leather, metal, it will break down. And the less you are dependent upon something you can’t control, the better. Strangely, one of the easiest things to control, in that respect, is another person. (Here comes the real Judy Gilliom.) It makes very little sense for me to try to sign a check with a pencil in my teeth when I can get a secretary to sign it for me with her initials under my name or when I can give someone a power of attorney to handle a checking account for me. The amount of energy I have to put into struggling with devices simply is not worth it. I don’t have that kind of energy to expend, and for a disabled person, time is of the essence. If you can use time well, then you can do the most that you’re capable of doing. These trade-offs are important, and making the right decisions makes the difference between whether of not you’ll spend all your life trying to overcome a disability, which is a thing you really can’t do in terms of changing yourself so you’re not disabled, or spending your life forgetting about the disability and being what you are.”

She does have some favorite mechanical friends: “I live with one hand on that dictation machine. I dictate everything. I tell people what to write on things, how to file things, when to water plants, what to remind me to do and when to come back. It all just goes on the tape. I have a speaker telephone, which works very effectively if you don’t mind sounding like you’re in the bottom of a well. Let’s see, what other devices? Power wheelchair. And these wrist extension splints. A sitting brace.”

She has a van. Does she drive?

“On no indeed! I don’t do anything. I drink out of a long straw, I use a dictation machine, I use a telephone, I talk a lot, I give orders. I’m very good at giving orders. But I don’t do anything. That’s not my bag, doing things.” Her bag is getting things done.

The basic decision, then was that for a high quad, a human being is the most reliable and flexible adaptive device available. Judy doesn’t mean a slave, a robot or even an attendant. She organizes whole batteries of people to become operative extensions of her own remarkable brain. Judy and her people interact with a mutual sense of respect and privilege, and the symbiosis is nice to watch.

Here’s another example of maximal efficiency. Judy chooses to live in a nursing home.

“A lot of people seem to feel that if they end up in a nursing home, that’s the end of life and they will never see daylight or any of their friends again. One of the facts about a nursing home is that it’s one of the most efficient mechanisms for getting an unwieldy body attended to. It keeps my body out of the way; they’re responsible for taking care of all the details. I have a full-time job and heavy volunteer activities. If I had to devote a lot of time to administering a mini-institution in my own behalf, I wouldn’t be able to do what I want to do. I don’t choose to spend my time that way.

“Sometimes it seems emotionally more appealing to live in a house. But a house is smaller; you can be trapped there rather than simply encased in privacy. The nursing home has a lot of space and a lot of staff, and the economies of scale make a lot of difference when they mean that you’re able to come and go as you please. If I arrive at two o’clock in the morning, there are people waiting to put me to bed. I really could not afford to hire someone to sit in my own house and do that for me.”

Once seen, the nursing home makes lots of sense. Judy’s social life is in no way defined by the predominantly geriatric population of the home, for example, because her friends live elsewhere. “They come in when they come in and we go out when we go out.” There’s a large patio for entertaining, and one of the filing cabinets in her room is actually a bar. There’s also the everpresent dictating machine and two desks. Many of her working hours are spent here, often with one or more secretaries, so it’s much more than just a bedroom. It’s a very tightly designed office that happens to have a bed and a bathroom.

With her basic living decisions made, Judy returned to her editing job and held it for another five years. That led to consulting jobs, developing policy and procedure in disability-related fields. She freelanced for the National Endowment for the Arts, consulted for the Office of Independent Living for the Disabled at HUD, served on the President’s Committee on the Employment of the Handicapped and also on the President’s Committee on Retardation. The nursing home was a humming place in those days, a nerve center for Judy’s far-flung mind network. At that time, she had three secretaries working for her and her three dictation machines were working overtime. And now this job:

“I work for the Interagency Committee on Handicapped Employees. It’s a group that’s able to consider issues and difficulties and barriers to employment of persons with disabilities. Because of the composition of the Committee —eight agency heads — generally we are very effective in getting things changed, in getting policies implemented very quickly. It’s a place where I feel I’ve been able to have some effect and have been able to see things happening, and that’s not always the story in government jobs.”

Here’s a hot tip: “Take charge of your own life. There are a lot of people who will try and tell you that they will do it for you or will imply that somehow or other they will carry part of whatever you consider your burden. But the real fact of the matter is that you are going to have to live your own life and that’s really the way that’s most fun.”

And another. It’s not what everyone wants to hear, perhaps not what everyone needs to hear, but it’s real to a lot of people: “I think that one of the most important things you can do is to give up hope. There’s a division of opinion in this field, I think, as to whether or not a person with a disability should maintain hope and always feel that life will improve and things are bound to get better, and you never know quite where your life will end up. That’s one point of view. I find it very counterproductive. The most important thing that happened to me was to have a few of my friends say to me, Look! Here it is! There you are. You go on with what you have from here. As soon as you can manage to give up the hope that things are going to be different, you can get about your life and do what you need to do and have a very good time being the person you are.

“A question that’s often asked persons in wheelchairs is, What would you give in order to get out? I find, as the years pass, that the answer is, Less and less.” Has it been good or has it been bad? “It’s been very good. Really, I think that my good luck is almost as phenomenal as my bad luck.”

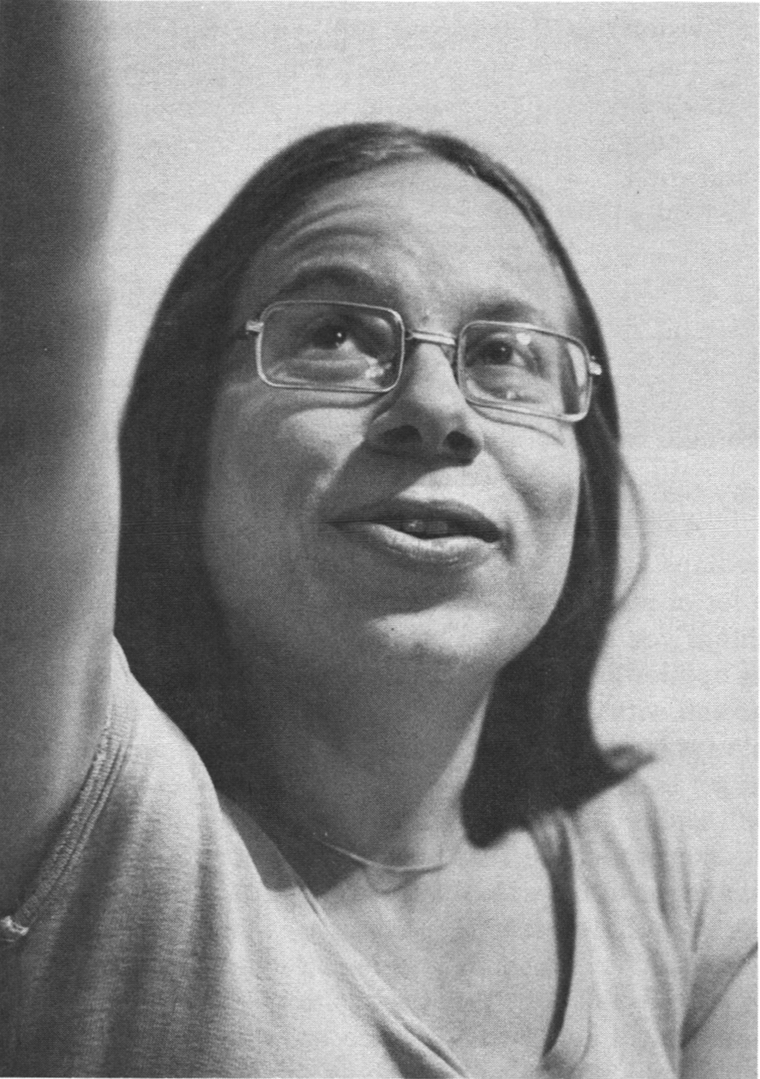

Susan Schapiro#

Here’s a Cinderella story. Susan was hurt in a car accident in 1967, when she was young, vulnerable and scared. Her first obstacle was simply leaving the hospital.

“I was there for eight months, which was really much too long considering what I actually did when I was there. But I didn’t want to go home, either, because it was very safe being at the hospital and nobody stared at me and it was pretty easy to live and I knew that once I got out into the real world, everything was going to be horrible.”

And was it horrible?

“Yeah! At first. I was 14 when I had my accident, and I had just turned 15 when I left the rehab center. Nobody at the center ever talked to us about what it was going to be like. I just figured that, being disabled, I was a social outcast and I could never have any friends and nobody would want to be around me. It was really bad. And a lot of what made it bad was my expectation that that was the way it had to be.

“When you’re 14, you don’t have many ways of coping with things like that. You want to be pretty and popular, and a lot of fairly superficial things seem really important. You don’t have a good perspective on what are the important things.” Mostly, she felt “ugly and klunky.”

Since life goes on even for distraught teenagers, and since, for Susan, a college education had always been a foregone conclusion, she went to “the only decent accessible school we could find,” which was, of course, the University of Illinois at Champaign. (By this time, U of I was far from alone on the list of accessible universities, but the word was slow in getting out.)

“I moved to Berkeley right after college and spent a year living here and working. There are a lot of places in the country where there are a lot of disabled people who are active, but there’s no place as highly politicized as Berkeley. And I just throve on it. When I came here, I got involved in the disability movement. If you’re politically interested, especially in the politics of disability, it’s very hard not to get caught up in things once you get here —this area is so charged with activity. And there’s a real strong feeling here that you’re OK, even if you’re disabled. It’s not something to be ashamed of. You’re not inferior. I had never been anywhere before where that was the general feeling. It is easier to be disabled in some places than in others, and this is one of the easier places.”

How were you doing with your ugly duckling feelings?

“I stopped feeling that way the majority of the time about four years ago. It was a long, slow process. Some of it was just getting older and getting a clear idea of who I was and what it meant just to be a person in general. Some of it was getting positive reinforcement from other people, and especially other disabled people. Some of it was a real concentrated effort on my part, sort of working on myself to make myself feel differently after I realized that it might be possible. See, for a long time I didn’t even realize that it was possible to feel OK.

“Then I started to realize that I could still have friends. My normal personality is to be pretty noisy, make a lot of jokes, be outgoing. After I became disabled, I became very quiet and self-conscious and mousey. And I found out that when I lost my self-consciousness or when I was just feeling OK about myself, people still did pick up on things in my personality that they had always picked up on. I found out that even men would do that. I started to find out that I could even have lovers.

“There’s a sort of process—I used to pretend that I didn’t mind being disabled, or I would pretend that I wasn’t aware of it, as a way of not being self-conscious. It wasn’t even a matter of being brave. I realized that when I wasn’t thinking about being disabled, or when I wasn’t worried about being rejected for being disabled, other people didn’t reject me because there was a whole self-conscious air that I would lose. When you set yourself up and all you’re telling yourself is, I’m-awful-and-I-know-you’re-going-to-hate-me, that’s what people pick up on. And when your inner feeling is that there’s no reason that people shouldn’t like you, that’s what they pick up on. So I used to pretend that I felt that way even when I didn’t, and the more I did that the better I actually felt.”

What prompted you to go to law school?

“I wanted to do something that would have some effect on my life or somebody else’s life. I didn’t want a job which just involved keeping the economy rolling along. I wanted to change the world, just like everybody. And I wanted to be involved in the movement. You know, sort of a professional disabled person, a professional crip, and it seemed that if I had a law degree I’d be a lot more useful.”

In 1978, Susan graduated from law school, passed the bar, and was sworn in. “It’s a beautiful credential to have after your name. There’s sort of a feeling of power being able to tell someone you’re an attorney. And I don’t look my age. I look like a cute little crippled girl; so it’s really important in negotiating settings to have something that gives me clout, even though, in a way, it’s artificial.”

She works in the Disability Law Resource Center, a division of CIL (see The Berkeley CIL), along with five other attorneys. The Center deals with disability rights in an overall sense: landlord-tenant problems, employment discrimination complaints, insurance discrimination and education.

“We just finished writing an amicus brief for the Supreme Court. The first 504 case is at the Supreme Court right now, and there’s a chance that they’re going to limit severely the whole interpretation of the law. It puts me right in the forefront of a whole new area of law. There are hardly any precedents yet and the whole thing is burgeoning.”

What else does she do? She gives lectures on sex and disability, mainly to non-disabled audiences. She feels that the general public has a tendency to discount the sexuality of disabled people, to assume that we’re asexual. She also knows she had to educate herself:

“I used to feel that I really couldn’t have real relationships because I thought that, as a disabled woman, I wasn’t as desirable. I figured that there was really no reason for anyone to be interested in me if he could have a woman who could walk, totally discounting my whole self and my uniqueness as a person. I didn’t feel really good about myself until I started feeling sexually attractive, feeling that I could function, not competitively, but on an equal footing with any other woman.”

Sports: “I didn’t consider myself athletic before I broke my back, but I did like to be really active. And then I just stopped. For a long time I felt a real need for ways to expend energy, but somehow the idea of wheelchair sports seemed silly. I guess I was still in my angry stage; I felt that if I couldn’t do stuff the right way, I wasn’t going to do it at all. That’s a really stupid feeling, that one way is right and some other way isn’t. Any way you can do something is the right way to do it.”

The missionary position of mobility?

“Exactly. And it’s so stupid. Anyway, I found out that wheelchair sports are a lot of fun.”

She started playing basketball, then gravitated to track events. She pushed the 1978 Boston Marathon. She canoes and rafts and is exploring wind surfing. She’s made films. She co-authored a book. Does one have to be a compulsive overachiever to succeed in disabled life?

“I don’t think you have to be driven by ambition to be able to live happily with a disability. Maybe you need a certain motivation to go out and force yourself to keep living, force yourself to keep being part of the world. But it doesn’t have to be linked with ambition or motivation in other areas of life. You don’t have to be a superachiever to go through the kinds of changes that I went through.

“I think the real secret of making it or being happy is just feeling good about yourself and doing whatever it takes to make you feel good about yourself. I’m sometimes driven to achieve because that is one of the things that does make me feel good about myself, but I don’t think everybody needs that in order to become self-satisfied.”

For that counsel, Susan Schapiro, fledgling attorney at law, should send us all a bill.

Then the rains came back to California, and we hustled equipment into the van as Susan hurried back into the two story house which she shares with her boyfriend, another tenant, a dog and a cat. As she skirted the doggy-do on the ramp. I thought of the 14 year old girl who had been so devastated by her accident and asked her what she wanted to do in the future.

“I want to be important. I like to have people know who I am.”