Lives I#

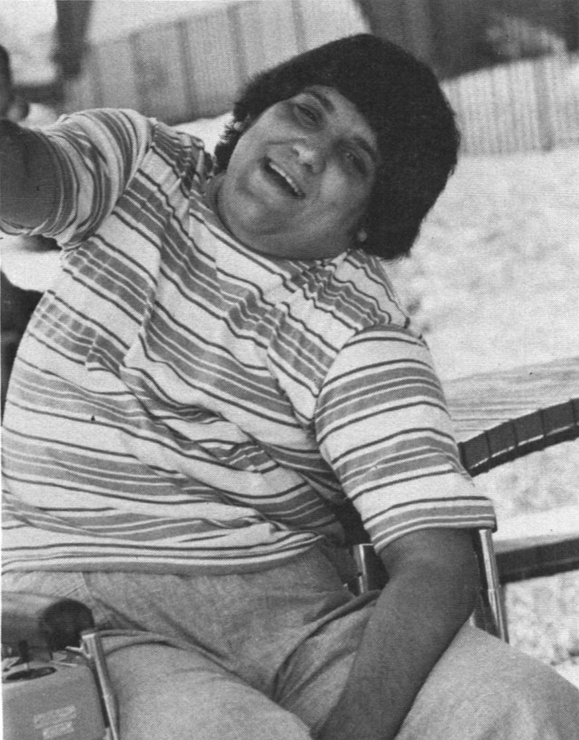

Fred Cheshire#

Fred was 31 years old in 1977, and doing fine. He’d survived 10 years of marriage and a recent divorce, eight years of school teaching, and had a job with unheard-of freedom teaching unusually gifted elementary school students. He was also coaching archery and his kids were getting to the Nationals year after year. He had a new girl friend, Debbie, who was with him the day he hit his head on the bottom of a swimming pool and became a C5,6 quadriplegic. He lay on the pool floor, fully conscious, until Debbie fished him out.

In 1979, Fred’s life has changed. He’s still got that incredible job, he’s still sending archers to the Nationals (one of his protegés recently won the Championship of the Americas in Brazil), but now he and Debbie are getting married in August and he’s working on his doctorate. Now he values time so much that he’s a little like an electron—he appears to zoom from place to place without traversing the intervening distances.

Fred was initially convinced that his teaching career was over. That was before the flood of visiting colleagues, administrators, and, especially, students, all of whom wanted him back. They ramped the school, reserved a parking space, and students from dozens of neighborhood schools raised much of the money needed to buy a van. I don’t think he really had much of a choice: “When I got back, I looked at them funny, they looked at me funny, probably for a day, and after that everyone accepted that they had a wheelchair person on campus.” So much for the dread reintegration blues.

Fred’s accident was in June. He started teaching one day a week in November, while still living at Good Samaritan Hospital, and within eight months was working full-time. Speedy.

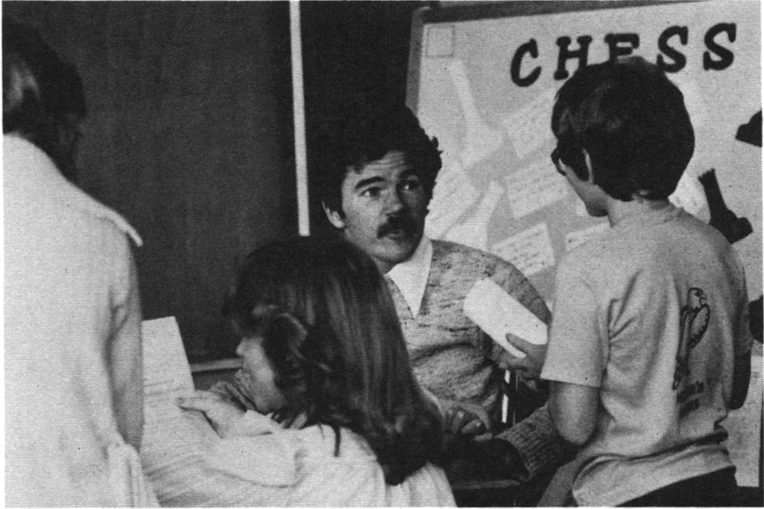

It’s easy to see why he was in a hurry to go back to work. The kids all have theoretical IQ’s checking out between 130 and 160, and it’s a constant multidimensional chess game to keep up with them. Fred likes the game: “It’s almost an escape to work with my students. That’s where I get my reinforcement —from working with students and working with people, fitting myself into an environment where I feel productive.”

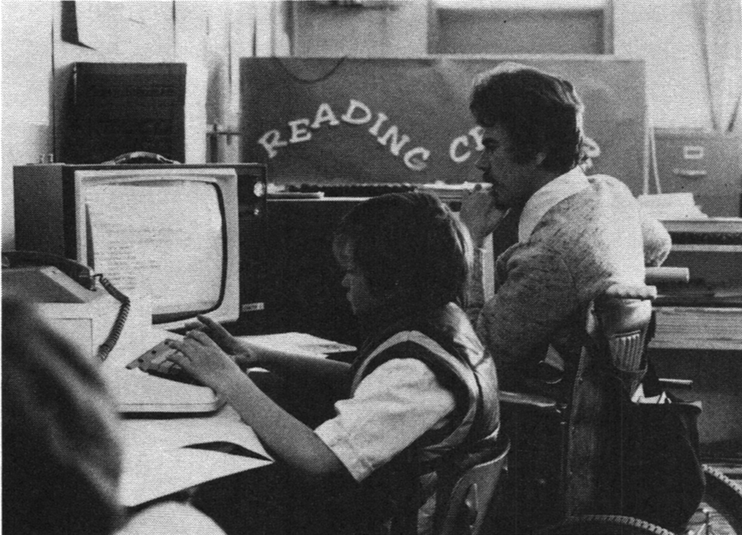

There’s a fantastic scope to what Fred does. He can coach one student through a simulated whale migration program on one of his two classrooom computer terminals, simultaneously offer suggestions to another student on an algebraic logic problem, listen to yet another describe an independent study project, then bring them all together to practice archery. He has an amazing capacity to direct full attention to a multitude of activities and levels at once. His classroom is a very busy place.

Consequently, his classroom is a madhouse. Or it would be if Fred weren’t so good about organizing his kids so that things get done easily and efficiently. Being able to walk might actually slow him down, for he’d lose some of his highly developed knack for delegation. As it is, the room is disorderly in that everyone in it is doing something different. It’s rowdy, because the students feel free to interrupt Fred whenever they need his help. And it’s one of the most creative learning environments I’ve ever seen, because the kids have chosen their own projects and are aggressively learning as fast and as hard and as much as they can about what they want to study.

Fred suggests a similar approach to learning about SCI: “Learn everything about wheelchairs, leg bags, how people are going to be talking to you — anything that goes on around you, ask why. Ask why it’s happening and understand it. Don’t ignore a thing. Learn everything you can, because it’s going to make your survival a more positive experience when you get out into the world.”

“Talk to people a lot; don’t get engrossed in your own mind. One day you’re going to feel up on something, and another day you’re going to feel down on something. One day you’re determined that you’re going to do one thing with your life, and the next day it’s going to be another thing. And that’s fine. That’s natural. Go through all those changes. Play with a lot of different ideas until you find what’s comfortable.”

Fred seems to have found what’s comfortable. I asked him if he ever was subject to depression, and he said that he’d been swamped with so much positive input from people, his community and his church, that he hadn’t ever been depressed. And after a moment’s thought: “I don’t think I’ve ever had the time to get emotionally down.”

Gwen Ruona#

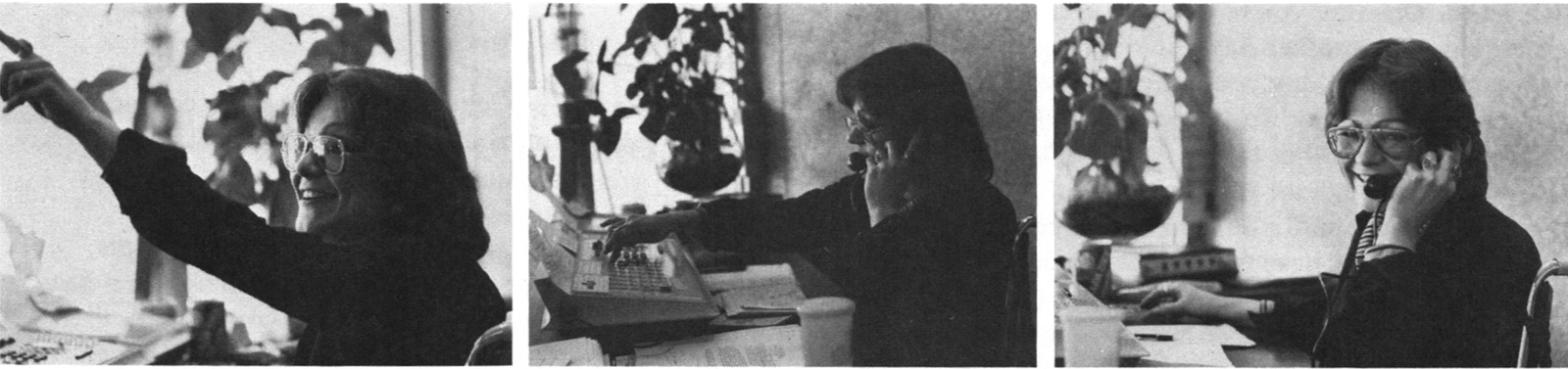

“I like dealing with people. I like the contact with all types of people and it’s like an education, constantly, because you have first contact with everything that happens, that comes in.”

It’s a very good thing that Gwen likes people, because she sees and talks to more of them in an hour than I can handle in a month. She works the switchboard at a large television station in Denver.

Here’s a tape transcript:

Good afternoon, KOA. Yes you may. One moment please.

Good afternoon, KOA. Dick Clark’s Live Wednesday? It’ll be on from nine til ten on the thirteenth of December. You’re welcome.

Good afternoon, KOA. Wednesday Night at the Movies? From seven til nine will be the New Adventures of Heidi. Thank you, bye-bye.

Good afternoon, KOA. That’s right, we have taken it off the air completely because they haven’t been paying their bills. No, what’s being scheduled in its place is 700 Club; that’s also a religious program. Uh huh, lot of people feel the same way. OK? Bye.

Good afternoon, KOA. Pictures of the cartoons? OK, let me put you up to TV Promotion; they should be able to help you.

Good afternoon, KOA. I’ll put you through.

Good afternoon, KOA. We’ll have a Flintstone Christmas Special from seven til eight on the eleventh of December. Uh huh, thank you.

Total transcript time: one minute and 15 seconds out of her eight-hour day. During the same span of time she has buzzed 10 people through the security door, handed messages to several and communicated non-verbally with all. Gwen is no switchboard operator; she’s an organizer, a choreographer, a catalyst, a power broker. She runs the place.

Here’s Gwen conducting:

Vital statistics: Car accident, 1974, T5 para.

“I just laid around and collected Social Security, trying to get myself together to see what I really wanted.” There was a year’s gap between her accident and her job at KOA which she feels was the most depressing time of her life. But…

“When my accident happened, I was 21 and I’d done some living. My life wasn’t all that easy, and I’d been through a lot of ups and downs. But I always picked myself up anyway, so when the accident happened it didn’t bother me.

“It’s amazing that there are a lot of people willing to help you, and really want to help you, so there is no excuse that I can’t find help or someone’s not willing to help me out, because there always seems to be somebody around that would want to do something for you.”

While she is often frustrated by her wheelchair, she says she is never embarrassed by it. And I believe her. She’s got one of those invisible wheelchairs, the kind you can’t see because the person in it doesn’t know it’s there. She emanates an aura of pure communication, and it works.

Gwen lives in a totally accessible apartment with a boyfriend she met at work: “We clicked off, he just moved in, and that was that.”

And sex? “There’s always someone out there for everybody. And there’s so many different ways. If you have any imagination at all, you can make it successful.”

Gwen sees herself as a sort of mother confessor, an inspiring example and a good listener who identifies with other people’s problems. Most of the people she buzzed through the security door looked as if they wanted to stop for advice, consolation or a good laugh. I felt that had I not been there, they would have.

Her aspirations? She wants to do voice-over for commercials and public service announcements, and perhaps eventually produce documentaries. She has the qualifications, but is frustrated by the current inaccessability of the announcer’s control room. That can be corrected, but when it happens KOA will be very hard pressed to find a halfway competent benevolent dictator to run their main show as well as Gwen Ruona.

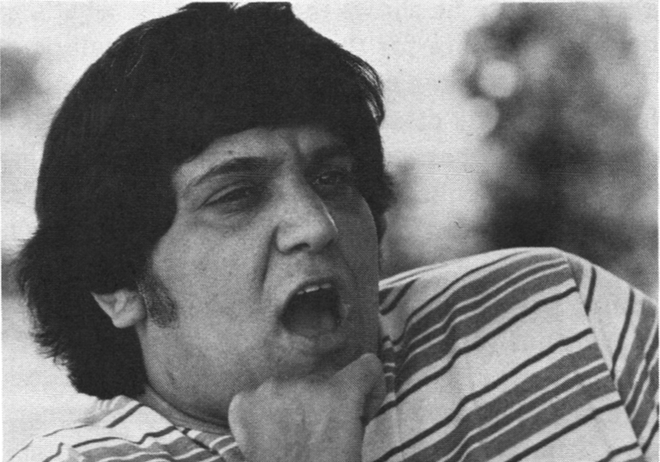

Stephen Epstein#

“Two weeks ago, I hopped on a plane at nine o’clock in the morning in Miami, flew to Denver, got in at 12 o’clock, got an Ambocab to Craig (Hospital), sat in on a medical conference, met the parents and the kid who was injured in the case, caught the 6:45 back to Miami, and was back home at one in the morning.”

A day in the life of Steve Epstein. Four days later, he and his wife drove their van back to Denver. He’s just finished his re-evaluation and now we’re talking.

“I once cut school and went to fly a kite with my wife. We were going down this embankment at Golden Gate Park, and I hit a pothole and went flying. Down the hill, about 75 feet, I went flying out of the chair, chair went flying, batteries went flying, and the whole time I’m rolling I’m going, I’m OK! I’m OK! I’m OK! I’m OK! I ended up at the bottom with the batteries on top of me, the wheelchair on top me; Gail couldn’t get down to where I was. We got to the doctor, Doctor Traynor says Don’t worry if you broke your back; you’re a quad anyway. They checked my leg; I didn’t break it. We plugged the chair together; it worked. And the grass stains came out of my pants.”

This guy’s like every stand-up comic you ever saw, except, of course, he doesn’t. He’s a rolling mouth, a man totally lacking a sense of embarrassment, an invulnerable self-image moving out on wheels. He’s great. He’s an attorney (“I’m not a lawyer; lawyers hurt people”). He’s litigious, which is to say he has a sue-the-sons-of-bitches attitude. He’s a crusader for gimp rights. He’s Saint Stephen. He’s funny, angry, compassionate and speedy. He’s one of those people you’d rather let talk than talk about.

Accident: Diving, upstate New York, 1968. Sixteen years old. “They pulled me out, punched me in the face and got me breathing. They said, You’re OK, you’re only paralyzed. There was a doctor on the scene. He stuck a pin in me, he said C6, and he was right. I’m a C6 quad.”

Rehabilitation: Twenty-two months (!) at a center in New York state. Bad. He received the kind of treatment he’s now fighting. High School and rehab completed simultaneously.

Schooling: Undergraduate degree partly funded by DVR. Graduated, met and married Gail, and went to law school in San Francisco. He paid for his own post-graduate schooling by taking out a loan (“I didn’t want to deal with DVR at all, it wasn’t worth it”).

Why law? Because he’d met Sidney Golman, an attorney and pioneer in getting cord injuries to good care, and Doctor Robert Jackson, medical director (now Emeritus) at Craig, who provided most of that care. Together, they gave Steve a sense of mission which burns brightly today. And Sid promised him a job when he passed the bar exam.

Steve passed, worked for Sid for a year, then started his own practice in Miami. He works in Rehabilitation Medicine, which, for an attorney, means insurance claims, no-fault, workers compensation, liability cases and medical management. Not too surprisingly, he specializes in SCI and brain damage. And to it all he brings a sense of compassion for the injured party and a sense of outrage at the medical care doled out by most hospitals. (“It’s a violation of your body. It’s rape.”) He’s respected by gimps and insurors alike, because he shows them both that what’s good for the gimp is sauce for the insurance company.

Here’s a sample of what Steve thinks about options for the severely disabled: “We put people in all these weird stereotypes, and one of them is that all gimps should go to college because the only way you’re going to get back into things is to do that. I just don’t believe it. I think the key to everything is choices. I think the people have to make choices, and not the insurance carrier, not the DVR, and not the person who’s managing the claim. The real purpose of rehabilitation, of managing cases and bringing people together, is to give them all the choices and let them make the decisions. There’s so many people out there making choices for other people who are disabled, it’s ridiculous. The only choices belong to the person who’s disabled, the injured party — being able to decide that you want to do nothing, you want to do something, you want to do everything. That’s his choice. But the point is that most of the time, when a decision is made, it’s made because there’s no alternative. And that’s what I resent.”

On motivation: “Most people fall in the middle; their lives weren’t so great or so bad when they got hurt, and they’ve gotta go reconstruct. The problem is, you need the tools, and people are very rarely given the tools. You see guys doing things like intermittent catheterization four times a day, who take three or four hours to do bowel programs. How the hell can you have a life if it takes you three hours to crap? It’s crazy. How can you motivate somebody who doesn’t even know what’s available to him? The answer is information and choices. Then you’re no longer disabled. Then people will be a lot more motivated.”

He feels that some of us who flail about more than necessary are victims of our own attitudes: “They perceive that their life or their self has ended. My self hasn’t ended. I’m Steve Epstein. I’m gonna be Steve Epstein until the day I die, and that’s not gonna change because I happen to be a C6 quad.”

He’d like to see SCI’s shuck what he calls their I’m-not-gonna-walk dance, and abandon the endless search for recovery, waiting for a complete return to normalcy. “There’s normalcy here in the wheelchair, and that’s what I think a lot of people miss. SCI is really a minor thing. I know people think you’re crazy when you say that, but it’s true. When you have your mind left, when you can still create, think, do things that are great, that’s what it’s all about. Hell, I’m all here. The only thing is I can’t walk. I roll places instead of walking. Sometimes I roll faster than people can walk. Big deal!”

Attitudinal barriers: How do you change them? “Easy. Just go out and be people. Be yourself. Travel, go shopping, mix, talk, live. Live life, that’s the real key. I mean, how many people just exist? Just go out and be yourself.”

Parting shot, offered with the disclaimer that, in Steve’s lexicon, “nigger” is a political word, not an ethnic one: “Gimps are the last, the final and the only niggers in our society. We are because in our own definition we allow ourselves to be hidden, we hide in closets and think we’re different. I don’t allow anyone to think I’m different.”

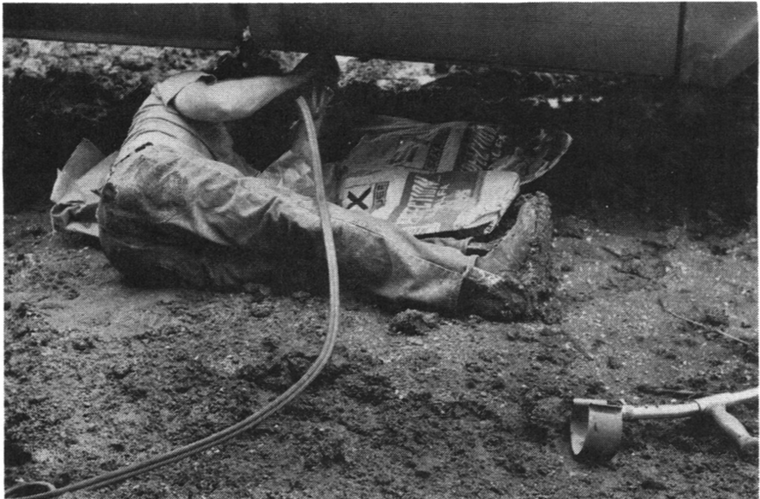

Sam Hunter#

1971 wasn’t a standout year for Sam Hunter. He fell seven feet from a building and fractured T12. He went to a general hospital, spent over four months on a Stryker Frame after a T10-L2 spinal fusion, and was told by his doctor that he might be able to get around in a wheelchair if he was lucky.

In 1972, things looked up a bit. He spent a few weeks at a SCI Unit, learned to walk on braces, and got enough functional return that he’s neurologically L4, which enables him to get around well on crutches and one long leg and one short leg brace.

Sam went back to the Florida marina that he’d managed before his accident, but his former employer, himself a T5 para, told him he had no need for a handicapped individual in the business. His wife divorced him. 1972 wasn’t all that hot either.

Sam met Joan, his second wife, while visiting Colorado for a check-up. Joan was from a farming background in Nebraska, and Sam was born and raised on a farm in Michigan, so they shared some common blood and a few other things as well. They moved to Nebraska, bought a small farm, got married and started to build a life.

Sam’s farming over 900 acres now—soybeans and corn, both dry land and irrigated. He puts up some hay, a little alfalfa and is starting a feeder pig operation. It hasn’t been easy, but it’s what he wants to do.

“You might as well do something you like. Who wants to go to a nine-to-five job in an office and let the walls close in on you all day? It’s hard to explain. I like working with livestock and I like to grow crops.

“Through the tough years and the dry years before I put in the irrigation well, I took every damn dime I could scrape up from my benefits, and my wife worked and she dumped everything she had into it, and there’s times when we ate, but we didn’t eat so well. And now I’ve got it to a point where it’s self-sustaining and ’I’m starting to realize some profits out of it. And I don’t want it ever said or thought that the government helped me on this. Because that damn little three hundred-odd dollars a month sure as hell didn’t put this place together.”

Sam Hunter has a problem. His farm, though doing well, is still marginal. Any farmer endures fickle weather and markets, unpredictable fluctuations in cash flow and very scary mortgages, and Sam still needs his benefits to keep his farm. The only way to keep them is to be listed as totally disabled.

“Either you are, or are not, handicapped. If you’re considered 100% disabled, you can’t earn a dime. But if you’re actively engaged in employment or a business of your own, then you’re not considered, as far as HEW goes, as 100% disabled. You can become gainfully employed and self-supporting without their help. Either you is or you ain’t.”

Sam’s in between. He thinks that in two years, he could make it on his own. In the meantime, he needs his benefits.

“Just at the point where you think you’re gonna get going good, and it’s a little greener on the other side of the fence, and just before you can climb over that fence, someone turns on the juice and fries you good. And that’s the only way I can put it.”

So Sam pretends that someone else is farming his land, and hopes that things will stay level a little longer. And while he’s pretending, he’s a working fool.

There had been an inch of rain the night before we arrived, and nobody was turning a wheel to farm. Sam’s first act of hospitality was to pull my van out of the mud. Then we had breakfast with Joan and his dad and new baby. Then he announced that since he couldn’t work today, he was going to relax by cutting the back off an old pickup to make a utility trailer, and he was off swinging his way through the mud, crawling under the pickup, then over into the engine cavity with an acetylene torch. The man moves like a buzz saw. I asked him how he handled the physical demands of farming, and it was obvious that he doesn’t consider it a remarkable feat:

“Everything’s so mechanized nowadays. You don’t lift much because you got hydraulic loaders on your tractors. Most of the equipment is hydraulically operated. Sure, there’s things that’s difficult. That’s one reason my neighbor and I, we plant together because he’s able bodied. With us two working together, it saves him dollars and it saves me having to hire help.”

He handles his own harvest. “You combine it, you augur it into the truck, you back your truck up to the augur, and you augur it into the drier, and you augur it into the bin. I mean, what’s the manual labor involved in that? It’s all mechanized.”

And that’s all there is to it. Plus a lot of savvy and guts and hard work and getting to know the banker real well and maybe keeping the feds in blissful ignorance for awhile longer. But it’s a little bit like being the first man on the moon and not being able to tell anyone about it. He’s justly proud of his accomplishments in the face of his injury, but who can he tell?

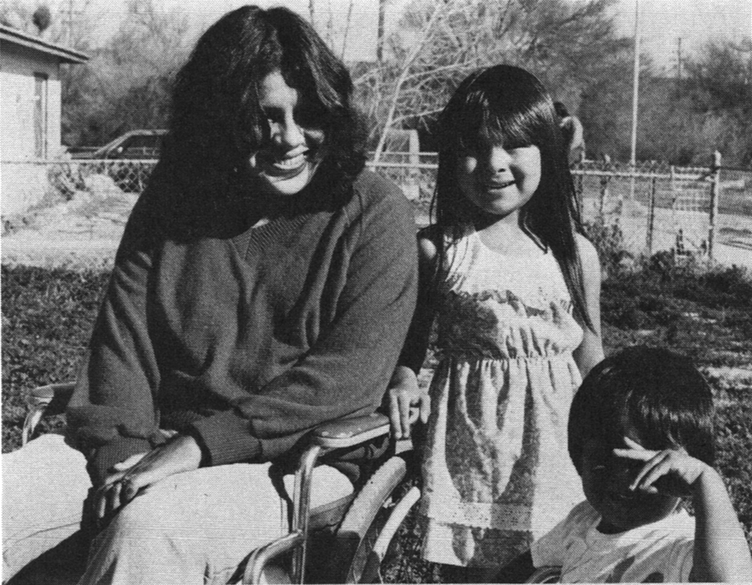

Deanna Gonzalez#

Deanna’s a Papago Indian married to Frank Gonzalez, a Mexican-American. She has three kids, raises them without hired help and is a C6,7 quadriplegic. In fact, two of the kids, Spot and Puppet, were born after Deanna’s accident. That, I thought, is remarkable.

Well it’s not remarkable and it was a mistake for me to think so when visiting her.

See?

The Gonzalez’ live in Ajo, Arizona, a small town in the desert southwest of Phoenix. The desert is beautiful and the town is not, being a typical Phelps-Dodge copper mining town with huge stack, designated wastelands, blowing tailings, proliferating mobile homes and, presumably, a grateful work force. Frank works for the mine, but this day he’s tinkering with an old Scout which he says hasn’t run in months.

The house is modest, surrounded by a fence, dozens of kids and dogs, and is an unpretentious part of a pleasant neighborhood.

Deanna invites us in, and I sense a shy, warm, personality. I prepare to tape a tale of remarkable achievement.

There’s not much remarkable about her accident, which happened in a car wreck on the way to a basketball game. Rehab at Good Samaritan, her high school diploma work completed at the same time. So I got on to the good stuff.

Why did you decide to get married only a year after your accident? “We wanted to get married.” Yup, it was a dumb question.

Did you have the kids intentionally? “Yes.” Did you consult with a doctor first? “No.”

And on the saga of childbirth: “In a way it was easier. I didn’t have to feel the contractions. But dysreflexia, it was real bad when I had Spot and Puppet, during labor.” That’s all. She did say that she spent an extra week and a half in the hospital each time.

Having run aground on heroism in the delivery room, I switched to the apparent impossibility of feeding, changing, bathing and nursing infants, let alone catching them once they can crawl. It seems that the most spectacular adaptive devices she uses are a special cutting board for food preparation and a velcro-attached wheelchair table for bathing and changing the baby. For the kids’ clothes, she just avoids anything with buttons, zippers and laces as much as possible. Her real aces in the hole are Lisa, her seven-year old daughter who gets things down from high shelves, Frank, who does most of the shopping, and her mother and sisters who like to take the kids from time to time. Otherwise, Deanna does it all: cooking, washing, kid repair and maintenance, housework and the shopping when necessary. She insists that she has no special tricks: “Everybody has their own way of doing things.”

And slowly it dawns on me what’s so remarkable about Deanna. Here’s a hint: “Things just seem like I had to do them this way. I didn’t plan it, you know. I don’t know how to explain it. If I wasn’t in a wheelchair, I’d just do things in a certain way. But I’m in a wheelchair, and I just do them. Do you understand?”

And at last I do understand. What Deanna has done would pass unnoticed if she were not in the wheelchair. If Deanna Gonzalez has a remarkable achievement in her life, it’s a matter of keeping the ordinary, well, ordinary. She is who she is and does what she does. She lives an ordinary normal life. What’s so remarkable about that? It is kind of nice, though.

An engine roar from outside announces the resuscitation of the Scout. Deanna’s pleased, because she and Frank like to go off-roading in the desert. Frank comes in, all smiles and happiness, to wash up and crack a beer. Spot and Lisa, banned from the house while we were recording, return to tell us the good news about the Scout. They’re two of the most beautiful children I’ve ever seen. Puppet, who was asleep in a back room, gets an award only for his excellent manners, for we never heard from him. He may not exist.

Later, Deanna played outside with Spot and Lisa. It was a game involving a ball, a light meter, a trike, a lost shoe, a wheelchair and tenderness. There’s a lot of affection at this house, and it shows on the faces of its occupants. I didn’t know such a thing existed anymore, but it seems to be a nice ordinary nuclear family that works.

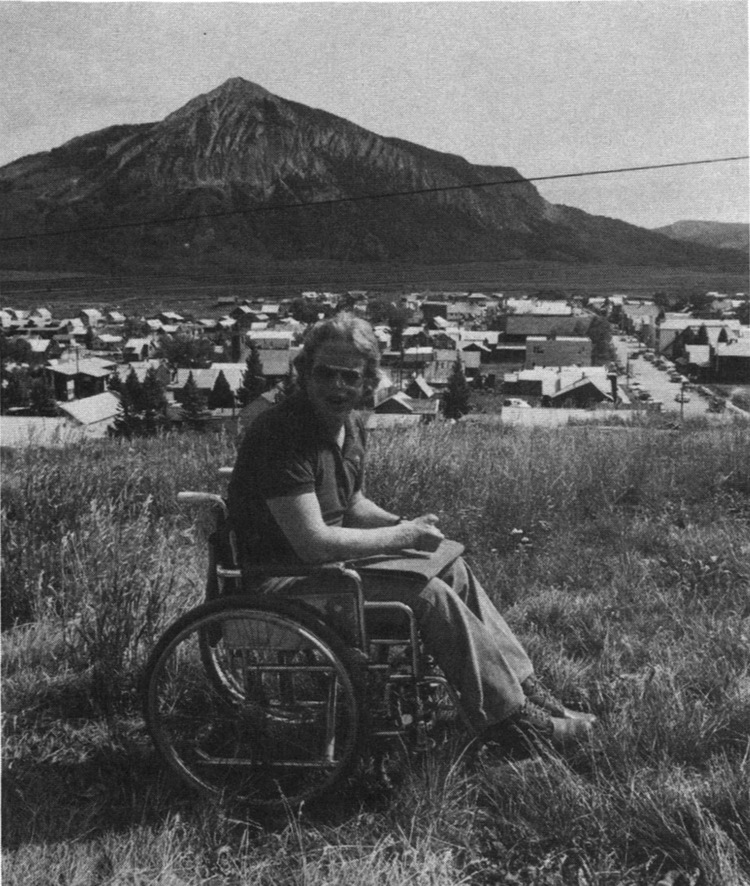

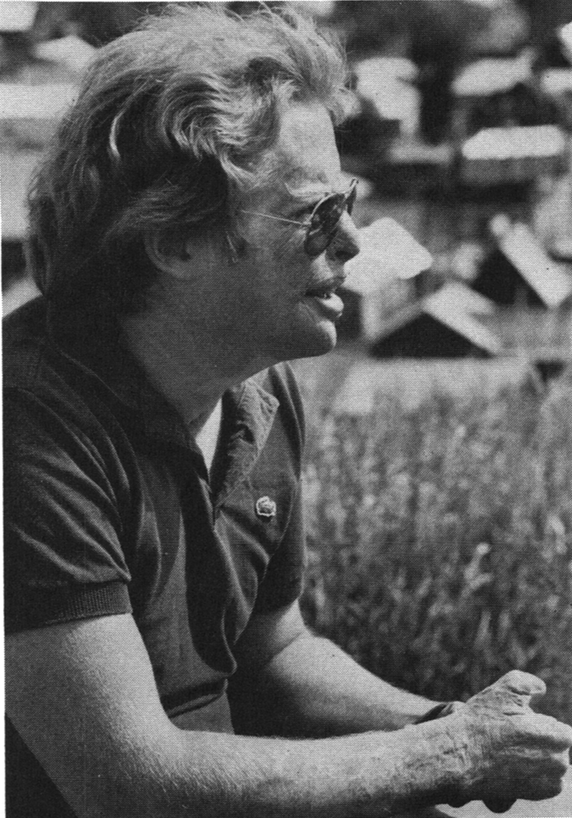

W. Mitchell#

Tell me about your job.

“I’m the Mayor of Crested Butte, and I get paid $25 a month.” That’s almost as good as SSI. “Almost as good as SSI. It doesn’t pay quite as well, but I have more fun.”

Crested Butte is a boom-and-bust mining town at 9,000 feet in the Colorado Rockies, celebrating its hundredth birthday in 1980. Its population rose and fell with the prices of silver and coal, with the presence, then absence, of the railroad, with the depression and with the advent of the ski area, but now stands at about a thousand souls.

Mitchell, as he prefers to be called, admits that his office provides few perquisites and only minor powers. He’s supposed to make proclamations, exercise police powers and handle complaints about noisy dogs and blowing dust. What do you expect for $25 month? But Mitchell works more than he’s paid for because he’s on a giant-slaying venture. He’s trying to throw AMAX, a three-billion dollar mining corporation, the hell out of town. Mitchell isn’t down on mining, but he doesn’t like it on his own turf. Not here in Crested Butte National Historical District. No matter that mining is the reason for the historical designation. Does that give miners the right to destroy their own history? As Mayor, of course, he has no authority to fight anything. As W. Mitchell, he’s well on his way to victory.

He’s a complex man. Everything he says is wall-to-wall dry humor punctuated by outbursts of pure corn. Good corn. He’s smoothly urbane, which paves the way for the times he wants to be vicious. For example, here’s his polite version of The Controversy:

“Among the other pressures that Paradise seems to experience, we’re in the heart of not only Colorado’s most beautiful mountains and natural recreation areas, but also in the heart of a large mineral district. A metal called molybdenum has been found right beside our home.” Since there is from four to seven billion dollars worth of this metal involved, AMAX wants it badly. Badly enough to destroy the mountain containing the ore, to build enormous tailings ponds (Mitchell calls them Slime Dumps) and to bring a work force of five to ten thousand people, plus their friends and relations and commercial camp followers, to a pretty nice mountain valley. “We’re trying to encourage them to put their interests elsewhere, where they’ll do less damage and more good.”

At lunch, the other Mayor Mitchell appears: “Putting a mining company in charge of a natural resource is like putting Dracula in charge of the national blood bank.” He gleefully shows us an article in Iron Age Magazine which states that the USSR is using four times as much molybdenum as it was 15 years ago, molybdenum from the USA. “So we’re tearing down Colorado mountains to build Russian submarines and warheads for their nuclear rockets.” Or another simile: “Restoring a mined mountain is like putting lipstick on a corpse.”

Such statements have endeared Mitchell to the national press. He’s been featured in the Washington Post, the New York Times, the Rocky Mountain News, the Denver Post, Chemical Week, Sports Illustrated, USA Discovery, High Country News, with more to come in Reader’s Digest and Harper’s. He’s made network television about a dozen times, and is repeatedly described as a one-man media event. I asked if the publicity is generated by the issue or by his being the Mayor-in-a-wheelchair.

“Oh sure, the chair has a lot to do with it. It’s a fantastic cause, but it’s the colorful aspect of this little town with the Mayor in a wheelchair fighting the mining giant. It’s really a classic David and Goliath, with the chrome as an additional factor.” Chrome against molybdenum.

Mini-history: High school dropout, four years in active duty in the Marines, GED, University of Hawaii, radio announcer, political campaign worker, teacher, construction transient, political science student, cabbie, gripman on a San Francisco cable car, and sort of a thrice-born gimp.

Mitchell’s disabilities came on the installment plan. In 1971, a truck hit his motorcycle, the gasoline cap popped off, Mitchell ignited and a man with a fire extinguisher put him out. His fingers were burned off and other burns rearranged over half his body, including his face. He was 29.

The motorcycle accident left him with a social challenge, but didn’t slow him down much. He started spending time in Colorado; first Aspen, then Crested Butte.

“Crested Butte was lovely, but it was pretty funky. It didn’t have most of the amenities that I was used to in Aspen. I’ve later found that to be a very nice characteristic.”

In 1973, with the money from a liability settlement, he bought a home and a new airplane. He holds and keeps current a commercial pilot’s license, instrument and multi-engine ratings, and is a commercial glider pilot.

“This was just a beautiful, beautiful place. And with my piloting, my airplane, I was able to have a lot of mobility.” It’s the mobility that got him. In 1975, he had to abort a take-off from Gunnison Airport because of iced wings. He’s a T12 para now, and is a changed man. “I’m being much more careful now —I don’t ride motorcycles anymore, although I do still fly.”

Mitchell went to a SCI center, and was back in Crested Butte three months later. What was his return like?

“I didn’t come out of the accident with a lot of psychological problems. Perhaps the experience of being burnt before, having that disability, conditioned me better for this. I had the luxury of growing up two doors away from a paraplegic and five doors away from a double amputee, so I’m sure that helped a lot in my understanding that you can do anything you want to. I found the wheelchair to be a restriction, but living in this small town, even with its three hundred-plus inches of snow in the winter, was pretty easy because there were a lot of friends, a lot of people to give an assist where one was needed. One of the real joys is living in a small town.”

In 1977, Mitchell was appointed to fill a vacancy on the Town Council, and first recognized the magnitude of AMAX’s plans for his town.

“I was alarmed, horrified, by what seemed to be the impact of that kind of development. I then made up my mind to run for Mayor, and it was a hotly contested battle. I formed a pretty sophisticated campaign organization, raised and spent large sums of money — $45 is the total I spent, which was probably more money than had been spent on any campaign in Crested Butte before that—and on election day, I was rewarded by a landslide victory. I won by 20 votes. It was 178 to 158. Somebody explained to me that that was 53% of the vote, which was better than Jimmy Carter had done.”

Mitchell’s up for re-election this fall, but feels fairly confident that nobody in his right mind would want to do what he’s doing for $25 a month. “To do the job I perceive needs to be done is a full-time job. It’s taken me to Washington 12 times, I’ve traveled seventy or eighty thousand miles, I’ve met people from President Carter to Jerry Brown to Teddy Kennedy to Secretary Andrus, Secretary Bergland, perhaps 20 senators, 50 congressmen and, of course, all the hierarchy of the AMAX Corporation. I’ve brought 20 to 30 million people’s attention to the issue we’re having here in Crested Butte. I’ve received and sent thousands and thousands of letters. It has been a truly amazing experience.”

That’s just dealing with the giant. In addition to the proclamations and the dog and dirt complaints, he is the Chairman of the Town Council and the liaison between the Council and the Forest Service, the BLM, the state and federal agencies which give planning grants to towns facing explosive growth, Gunnison County and the separately incorporated town of Mount Crested Butte, otherwise known as the ski area. “If I hadn’t got burned up, or been in a crash, I wouldn’t have enough money to be Mayor of Crested Butte.” That’s to say his settlement has been parlayed by shrewd investment — particularly in a company which he co-founded, Vermont Castings, which makes excellent wood-burning stoves —so that he can afford to spend 50 to 80 hours a week at nonremunerative work.

And the town hall? What edifice would house such a folk hero? “I have the distinction of having the least accessible town hall in America. When I became Mayor, I agreed to donate my salary back to the town so it could make the town hall wheelchair accessible. At $25 a month, I’ll have to be mayor for life!” Here it is:

“I don’t spend an enormous amount of time on handicapped issues, not because I’m unsympathetic, but because I’m already working 60, 70, 80 hours a week trying to save my town from being destroyed. It seems that by being this Mayor-in-a-wheelchair, just going out and doing business as a Mayor should do it —I think people see that I’m an active person and that a wheelchair isn’t a limitation to doing anything.

“The way I look at it, before I was paralyzed, there were ten thousand things I could do; ten thousand things I was capable of doing. Now there are nine thousand. I can dwell on the one thousand, or concentrate on the nine thousand I have left. And, of course the joke is that none of us in our lifetime is going to do more than two or three thousand of these things in any event.”

During my brief time around Mitchell, he was constantly surrounded by women, all interesting and some adoring. I asked him about relationships. “I’m a single man. I like the company of charming ladies, but so far they’ve all eluded me.” Do your burns and paralysis have anything to do with that? “It would be easy for me to grab that one and use it, but it doesn’t stand the test. It’s not valid. It’s nuts to think that you have to look like Robert Redford and have a million dollars in the bank to be happy in life. There are lots of people whose compatibility goes way beyond this physical thing.”

Recent foolishness and planned indulgence department: “We hear the argument constantly, when we’re trying to defend the wilderness, that the handicapped and the old can’t use it. Well that’s not so. I just completed a raft trip down the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, a raft trip that I doubt 200 people since man came on this earth have taken. I did another raft trip down Westwater Canyon, on the Colorado.” And coming up: He wants to buy a motorized sail plane which has the capability of self-launching and of landing at airports as opposed to hayfields. He figures this would be a good thing for a para. Besides, the hayfield might belong to AMAX.

Occupational advice? “Politics is one of the most interesting areas that I think that someone who’s injured can get involved in. For God’s sake, we need more brains and less brawn in politics these days. And if what you’ve arranged for yourself is mostly having to live a brain life, and less of a physical life, then maybe politics is an area where you could make a contribution.”

Hot tip: “You’ve already demonstrated you’re a survivor. You’re here, as opposed to most of the people who do to themselves what you did to yourself, and that is wind up in a graveyard. So why don’t you take the hint and do something with your survival skills? Go out and survive.”

Update: Mitchell ran unopposed. A few days before the election, I asked him What if he lost?

“You have a lot of image problems. You’ve done something wrong. What if you had an election and nobody came?”

On November 6, 1979, Mitchell was re-elected mayor of Crested Butte. By a landslide.

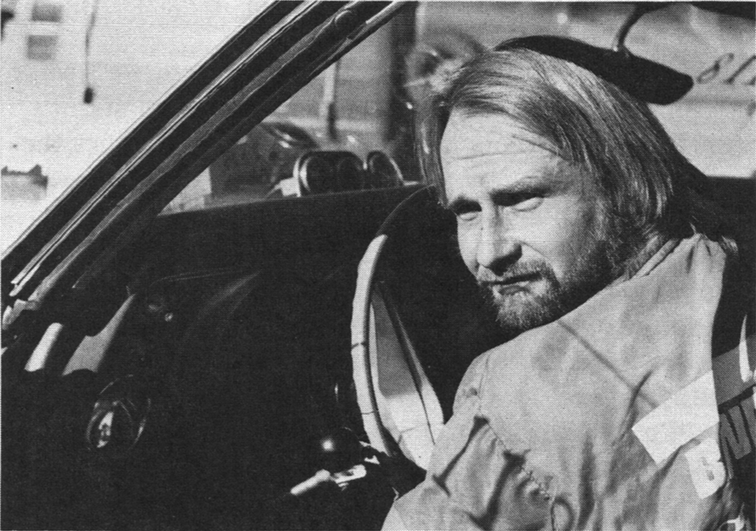

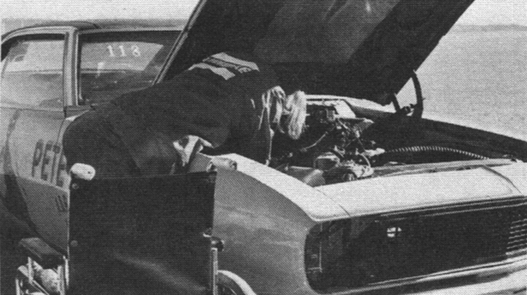

Pete Brown#

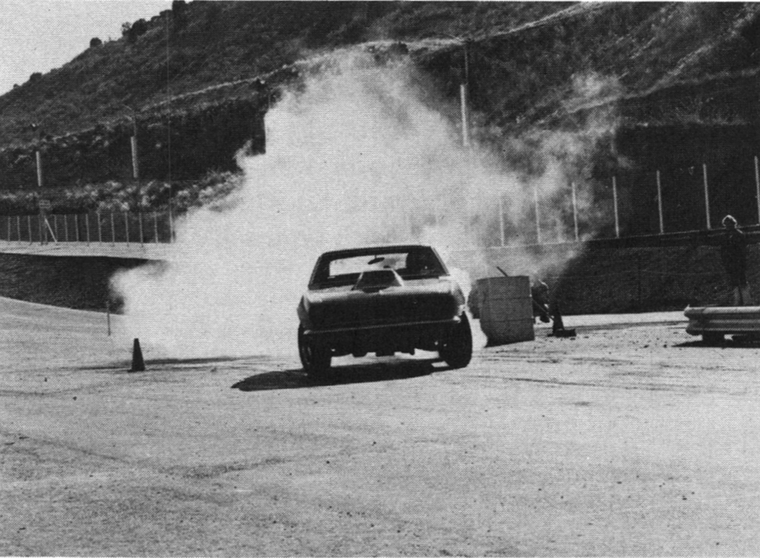

On August 14, 1976, Pete’s ‘55 Chevy was turning out good times at the Bandimere Speedway. In fact, he was going 176 mph when his tie rod broke. He kept the car on the track for a few hundred yards, thought he had it saved, and that’s when it started rolling. Pete jumped out and broke his back. The car rolled into a ball before it stopped.

Pete’s a wiry, intense person; a T12-L1 para. His speech is quiet and telegraphic, but he’s friendly. He’ll gladly show you pictures of what was left of his race car, and he’ll take you out to the garage and proudly display his new race car, a 68 Camaro.

October 24, 1978. Pete’s running time trials at the Bandimere Speedway, and isn’t happy with the Camaro’s performance. From his chair, he rolls up onto the fender (he doesn’t need braces to do this), has the head cover off in a couple of minutes, and pulls out a broken rocker arm. He’ll fix it himself—he does all the mechanical work on the car.

In the past season, Pete has raced 26 weekends, and he guesses that adds up to 200 individual races. It was a good first year for the car, and he picked up almost 1,500 competition points and a couple of sponsors. He feels that sponsors will eventually make the car self-supporting.

Is he as good a driver now as he was before his accident? “No, I’m kind of skittish of the car. I almost rolled this one about two months ago. Blew a tire.” Skittish or not, he races three out of every four weekends during the season and spends weekdays working to get the car ready for the next race. He also puts 50,000 miles a year on his van and spends time power-boating, trap-shooting, hunting and just going for trips with friends. And here’s what’s interesting: he doesn’t have a job and he’s not rich.

Often when we describe human success, we speak of employment or occupational accomplishments. It’s easy for a workaholic to assume that work defines the man and to forget that there are other significant ways to succeed in living. Or, for that matter, that man should define his own work. Indeed, there are lots of us who would define success as being able to not work, but somehow we think we have to work hard to secure that privilege. I think Pete’s work ethic is pretty healthy:

“I’m able to work. I’m not saying I’m not able to work. I’ve had a lot of people tell me that I should be getting back in school and taking up another trade, but I don’t need school to work. I know how to work on computers, I know how to work on machines, I was working at Acme Precision as assembly foreman … I’ve worked for IBM and Storage Technology. My favorite job was carpentry work, and I still do a lot of that. If someone wants something built, I can get the stuff and build it for him. I enjoy doing auto mechanic work …” But:

“It’s hard to get involved in something if you really don’t want to do it. And I really don’t want to do it. I want to do it, but I just don’t want to do it when I have to do it. You work enough to make enough money. I just live a normal life, you know. It doesn’t cost that much to live.”

Pete likes work alright; it’s jobs he doesn’t like. Amen. I like the fact that he’s not wasting much energy achieving other people’s remote objectives. He works for his own goals, and I call that a success. And if he can consume less and make do with less, I like that too.

As to the rest of his head: “I felt that I did what I did to me, so I have to live with it. You know, there’s no one else to blame. I can’t say I haven’t felt sorry for myself because I did it to myself, but as far as being emotionally upset, I haven’t been. No.”

I asked him if he was ever embarrassed by the chair. Turns out he’s embarrassed by “this raggy old chair,” but not by his new one. “I’ve been dating a lot of young girls here, and it hasn’t seemed to bother them a bit. I mean it doesn’t bother me; why should it bother them?”

Has the accident changed his life? “I have changed a lot. The people I’m hanging around with now are just a different type of people. Nicer people, you know. I just felt that I was going to change my life, and I did.”

Larry Quintana#

This guy is hard to figure out, as if he’s a front for some benign underground organization whose identity should be obvious to me but isn’t. He looks like Meher Baba and talks like a kindly Godfather, which is to say he looks wiggy and acts mellow.

He seems to run things, whatever those may be, and people around him anticipate his needs and wishes intuitively. There’s a sense of mutual dedication and devotion here, perhaps a sense of service, that I’ve seen elsewhere only in a Buddhist community I once hung around. Larry is incredibly tight with his friends.

His speech constantly alternates from literate college English and Spanish to equally literate and infinitely more colorful street vernacular. The latter has been somewhat suppressed here as a gesture to scandalizable librarians, but we’re all the poorer for the purging.

The speech shifts facilitate his role shifts —there are visible traces of radical revolutionary, love-and-light people-freak, teacher, preacher, racial synthesizer and compassionate urban guerrilla. The only adjective I feel safe with is charismatic.

He’s such a complex person, at least to me, that the only way I can describe him is to tell you the obvious historical stuff, and then let his various identities inform you about what has real significance for him.

And after all is said and done, I still don’t have the foggiest notion what Larry Quintana actually does.

Larry got it in a car wreck in 1964, when he was 17. Really got it. He’s a C5-7. Reclining electric wheelchair, arm braces and all.

Eight months later he was out of the hospital, having graduated with his high school class during the same period. He was soon working as a volunteer teacher’s assistant at a junior high school in his hometown, a job for which he later was paid. He knew he wanted something else, but didn’t know what.

The rehabilitation hospital wanted him to go for a college education, but his working class background made him feel that a regular job was the only route to self-esteem. He finally wrote Washington, DC, for help (“To whom it may concern”), was miraculously hooked up with State Rehabilitation, and was soon a freshman at Mesa College.

New lifestyle. The artificiality of any college. Coping with his body. School was hard at first, and he stayed with it only because of a lot of help from his friends. He ran for vice president of the student body, partly to make friends and mainly because the office carried a stipend. He won. He ran for office every year thereafter through graduate school, and won every election.

After a transfer to the University of Colorado, he was able to maintain a 4.0 grade point average. He also was married and acquired a lot of fiscal responsibilities, so he started hustling every government and university program he could find. He continued winning office, which now paid $200 a month. He just couldn’t understand why the campus wasn’t completely accessible yet, so he set up an accessibility advocacy program for which he earned graduate school credits. He had some Social Security, and his grades got him an excellent fellowship so that he could go on to his master’s degree in community planning. He received his postgraduate degree in 1974.

Three months after his graduation, he went to work for HUD as an intern planner, then as Spanish-speaking coordinator for the, region, then as a technical planner in Denver, and now takes care of HUD’s 701 Program (Comprehensive Planning Assistance for the Office of Indian Programs). His job is to evaluate and process planning grant applications from the various Tribal Councils and to facilitate outreach efforts through his field representatives.

For recreation, he teaches school. For nothing. He and his friends feel that a high school education is mandatory for anyone now, so they’re talking kids back into school and keeping them there by helping them in any way they can. He likes music, photography, fishing, going to the mountains, political exchanges and whatever his friends want to do. He’s still married, and he and his wife have been to Mexico twice. He doesn’t have a hired attendant unless travel makes it absolutely necessary.

And that’s all I think I know for sure about Larry Quintana. Here’s his version.

After SCI: “I know I bit shit for two years, I know I did. I mean, I hated people, man. I could not understand what in the hell was going on. Now all I can tell them is, you’re gonna go through this and you’re gonna do it yourself. Hell, I don’t know when you’re going to get over being depressed, but when you do, and when you feel like you’re not going to be crying every damn day, do something. Get out of bed, man. Quick!

“I woke up one morning, I was in Montrose and the air was really smelling good, and I took this surge of really good air and I thought, I’m really alive. I didn’t die. And I’m gonna do something. Today. And I think that can happen to anybody. You have to allow it to happen. And when it does happen, you’ll know, and that’s when it’s time for you to move.”

Has he changed? “I am not the same Larry Quintana. I went from Larry Quintana (Anglo inflection) to Larry Quintana (Spanish inflection). I wanted my own identity, and I was a totally different person. I know I’m not the same guy. There’s no way I can be ever-ever, and I don’t know if I want to be. I kind of like myself now.

“I’ve caught a lot of hell for my Diplomacy and Tact, as someone put it. People in wheelchairs have to be very, very to the point in order to get things done expediently. I think I have to be more aggressive than most people, because if I’m not, I can’t get my physical needs taken care of. I know I cannot walk from one place to the other, and if I’m in bed, or if I’m visiting, the fastest way of getting something done is to be very much to the point of what I need and tell someone. I think there’s too much hand-holding, anyway. Wasting time.”

Re sex: “I think guys in wheelchairs, if they would just learn. Hey, I can take care of that. Quick. And feel that way toward ladies. I think if you think you’re pretty, the ladies think so too. If you feel good about yourself, other people feel good about you.”

Failure? “If you don’t make it, you cannot blame it on the wheelchair. Don’t tell me that because you’re in a wheelchair you’re a tramp. Don’t give me an excuse — I can’t get behind the concept of failing and having a rationale for it. If you want to get behind the wheelchair for an excuse, I don’t respect you. It’s a copout. And it’s a damn good one.”

Discrimination? “I often wonder if getting into a car wreck, getting what most people consider messed up, hasn’t really been an attribute. Because I sure see some sad people that have no compassion. It seems they have no compassion for each other. I am a minority, I’m a Mexican, and I can be in the wheelchair and look at racism and tell other minorities: Man, I know. I know what it is to be discriminated against. To the bone. I think it’s terrible. Sad. Probably the most saddening thing of my life.”

As Larry points out, his friends look like the United Nations on parade. He feels that for a person in a wheelchair to make an ethnically derogatory remark is about as scummy as you can get, because that’s denying the facts of our own existence. I didn’t want to paraphrase in this section, but that librarian is breathin’ down my neck.

And about his recreation: “Almost my entire life, that is off work, is recreation. I just enjoy being alive. Actually, I’m probably just basically a happy person. I do not like depression.” If you should surmise that he thinks depression is an indulgence, I’d have to agree with you.

Offered without comment: “If you can’t find an attendant, you better find a lover that can take care of your ass. If your lover can’t take care of you, send her back home! Don’t make love to her. Tell her. I want you to expand your life, but I want my life to keep going. I love my health. I mean, if you love me, take care of me.”

Here is the most animated thing Larry said. You can’t see him light up with earnestness and pure benediction, but I could. You may not know that he can be cynically trite if he wants, but right now he doesn’t want to. Had this little speech come from Richard Pryor or George Carlin, you’d call it the affectionate wind-up. Well, Larry has a highly developed sense of theatre, but I think he believes this:

“The best thing for anyone to do, is SMILE, MAN! Get behind a smile, even if you don’t mean it. Because if you smile, and ask them to do something, they will enjoy doing it. People do not do anything they do not want to do. So don’t forget that man opening the door for you, or you (me), bringing that coffee up; you did it because you wanted to. People don’t do things they don’t want to do. So smile at ’em. IHELL, MAN*, I think the smile is the biggest thing you can give to anybody! Express a lot of love to people.”

And maybe, after all, Larry Quintana is not complex. Maybe I’m unable to recognize simple concern for all people expressed so directly, because that happens so seldom. This guy’s hard to figure out.