Lives V#

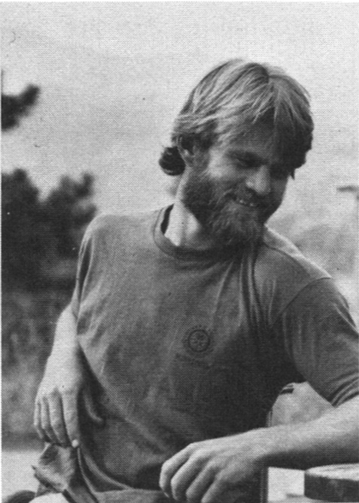

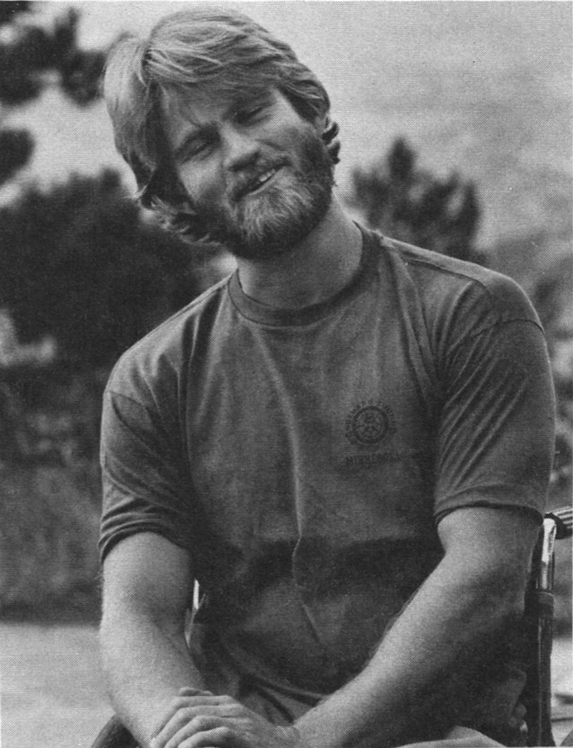

George Hohmann#

We’re in Tucson, sitting in a pleasant backyard patio chatting with George Hohmann. This man is pretty special, and I’m curious enough to start off with a direct question: George, you’ve been in that chair for 35 years. Has it been good or has it been bad?

“It’s been good.” And to George Hohmann, life surely has been good. You can see it in his face, which looks much younger than his 55 years, and you can see it in his satisfaction with home, marriage, children and career.

His career is mainly what the world sees, although he seems to have several careers. He’s just finished 30 years with the Veteran’s Administration, most recently as chief psychologist for the Tucson VA Hospital. He’s now planning to intensify his involvement with the University of Arizona, although he already holds a full professorship. He teaches courses in abnormal psychology and psychopathology, heads a psychodiagnostic testing assessment seminar, sits on a number of doctoral committees, directs dissertations and supervises clinical work. He crosses the country about once a month giving lectures and participating in seminars and symposiums. He has written papers on many aspects of disability, and, although he vehemently rejects the appellation, has been described by several of his prominent peers as the Father of Rehabilitation Psychology. He is, he’ll admit, a workaholic.

In 1944, when he was 20, George had survived the dust bowl days of the Texas Panhandle and was hoping to survive World War II. He took a bullet in his spine, had a T9,10 lesion and lousy expectations. “In 1944, there were no wheelchairs on a SCI ward with 60 people on it. The army would not invest in these wheelchairs because we were all gonna be dead.” So George was once again faced with a survival situation and took matters into his own hands.

He started school at UCLA in 1946, which was, at the time, a pretty outrageous thing to do. “People who were disabled, crippled if you will, stayed at home or in institutions, hospitals, nursing homes —they didn’t mess around out in public.”

George messed around a lot. He married in 1948, even though prevailing wisdom strongly suggested that wheelchairs and marriage don’t mix. The marriage is still strong. About the same time George collected his PhD, he and his wife adopted the first of two children, both now in their twenties and in graduate school.

[It’s interesting to note that in those days, the Hohmann’s were told that a disabled man was an unsuitable parent. It took years to beat down the resistance of the Children’s Home Society. In contrast, check the ease with which the Ludlows, a quad and his wife, adopted their children (see Bob Ludlow). Times have changed, partly because of people like George.]

Does he recommend adoption? “The adoption experience itself was very very rewarding. I don’t see how people could love a kid any more if they had borne them. I don’t know how there could be any more relationship with the kids than we have had.”

With wife, kids, doctorate and a job with the VA, George started messing around in the field of rehabilitation and took a strong interest in the psychosexual problems of returning veterans: “I think of people who are into human sexuality as kind of kinky people in general, and I think of myself as one of the straightest people I’ve ever known. But one of the problems was that the patients were saying over and over and over again, for God’s sake won’t somebody tell me what my sex life’s going to be like, and nobody would. There was nothing, prior to 1970, that dealt with What do people do, who have cord injuries, to make love? And how do you go about making love, no matter what your neurological condition is, or how do you incorporate whatever residual genital-sexual functioning one might have into a lovemaking pattern?”

George broke the professional ice by presenting a paper that addressed these problems, a paper which has been published and reprinted and become a certified classic. So that’s how George Hohmann, self-proclaimed straight, got into the sex business.

He dislikes “the assumption that the only kind of sexual activity that is desirable, that is effective, that is satisfying in the final analysis, is penis and vagina in a missionary position. I’m not putting down genital activity — it’s neat, it’s physiological, it’s biological — but I’m saying that sex is a many splendored thing and there are lots of ways of showing love and affection. To put that much emphasis on the genitals, it seems to me, is to bastardize the beauty, the closeness, that come from a mature relationship between two people.”

Of the newly cord-injured person: “They don’t understand that somewhere down the line, rehabilitation probably ain’t learning to do well what the doctor tells you; it is learning to do well that which you want to do. Maybe doing what the doctor tells you works and maybe doing the opposite works and you may have to tell him to go to hell. He is telling you how to be a patient, and if you follow all of his instructions, that’s what you’ll end up being. If you don’t follow all his instructions, you may end up being a human being.”

I submit that it is a measure of the respect and reputation he enjoys among his peers that, after 30 years of close professional association with doctors, he has not been most foully murdered in his sleep for his irreverent attitudes. Here’s some more:

“Life with a disability doesn’t have to be any way, except the way that you make it. Sure, there are reality things that one can’t do, but if you can’t do it that way, there’s another way you can approximate doing most anything you want to. If you keep trying, if you are active, if you keep yourself exposed to other people, if you seek stimulation of one sort or the other, you’re gonna get rewarded for it.”

About his own life: “The most unusual thing about my life is that it’s been so usual. We’re the average middle class family. I’ve had a good career, I’ve had a good wife, I’ve raised, together with my wife, a couple of kids that are fine youngsters, had the nice things of life and I’ve lived! It’s not everything, but it’s damn sure something.”

Parting shot: “SCI, like life, is an absurd kind of situation. And the only thing to do with absurdity — there are only two options— one is to laugh and one is to weep.”

The latter of which is patently absurd.

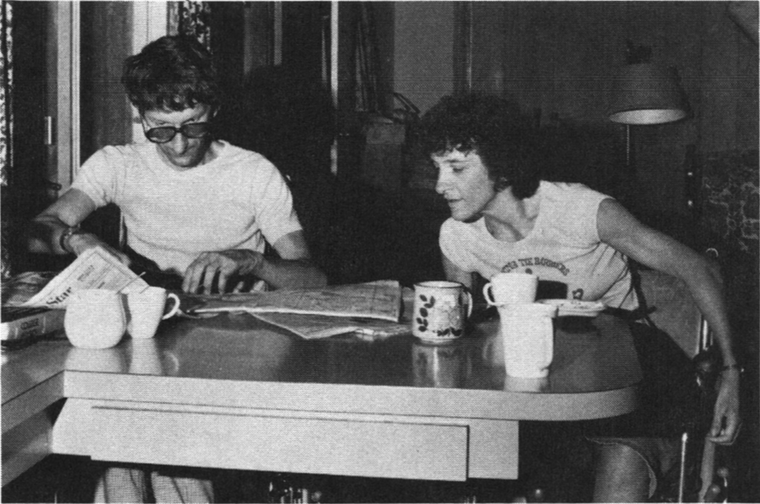

Jonathan and Sharon Wilkin#

They’ve been married for 14 years. They’re both victims of murderous acute-phase care, both C5,6 quads, both completely independent, both graduates of the University of Illinois and both successfully and significantly employed. And they’re as unalike as any two people could be. Jon: taciturn, expresses himself with shy/dry humor and precision. Sharon: lushly assertive and verbal. Their marriage, their lives and their home in Vienna, Virginia are all the results of a lot of caring and a lot of work.

1958. Sharon was 17, an exchange student newly arrived in Belgium, when she broke her neck on a ride at an amusement park. Perhaps from a need to quickly remove their casualties from the public eye, the park officials refused to let her wait for an ambulance and sent her off to a doctor sitting upright in a car, her head bobbing on her chest.

1960. Jon, riding a motor scooter, collided with a car making an illegal U-turn. He broke his neck and his arm, but had no paralysis. He was given emergency treatment at a small hospital in upstate New York where his arm was set but no X-rays were taken of his neck. After a night of tossing and turning, he was paralyzed.

Sharon stayed in a Brussels hospital for six weeks, then flew directly to a New York state rehabilitation center. She spent nine months there. “I learned to brush my teeth and wash my face and when I was discharged,

I was told— or my parents were told—that she would need 24-hour a day attendant care for the rest of her life.” Sharon was unimpressed.

Jon, after acute care, went to a different rehabilitation hospital in the same state, where he was similarly unimpressed. “I could do the same kinds of things, like brush my teeth.” And smile a lot? “No, you couldn’t do that. I was supposed to brush my teeth all the time!”

Separately, both Jon and Sharon had heard that the University of Illinois at Champaign was the only university in the country then accessible to students in wheelchairs. It was accessible because of the fiery determination of one man, Professor Timothy J. Nugent. In those days, Tim interviewed all potential scholars before acceptance.

Sharon: “He’s my great, great savior. He is the person to whom I attribute my entire life. And the interview with him was: Can you dress yourself? No. Well, why can’t you?”

When Sharon arrived in Champaign for her first semester of school, she was put through a make-or-break functional training week. In that week, she became almost totally independent. In one week, she overcame the inertia of a year of being told she couldn’t do things.

Jon: “Tim Nugent and I got into a real shouting match. Yes you can! No I can’t! Yes you can! Except it took me three years instead of a week to learn to do things.” (Jon has less sensation and motor function than Sharon, and spasm which he learned to deal with only after a temporary alcohol block.)

By 1965, when Sharon had her M.Ed. in counseling and Jon was finishing his master’s in mathematics, they got married and moved into a modified trailer home.

Sharon: “It made me very angry for people to ask before we were married, Well how are you going to cut things, how are you going to handle hot things, how are you going to do this? And at that time, neither of us drove and neither of us thought we would ever be able to drive, because of our spasms. (Sharon now drives a van, and Jon, a much-loved convertible.) Now, as I look back on it, it almost horrifies me to think of what Jon and I went ahead and did without having any answers.”

Jon: “But a lot of the time, people don’t try things because they don’t know how they’re going to do them, and they’re afraid to experiment with different things.”

Do traditional gender roles get changed? What I’ve seen so far is that both of you make money and both of you make coffee.

Jon: “It’s a lot more traditional then she’d like it.”

Sharon: “Yeah! (Jon chortles softly) Now this is a serious problem. Jon was raised in a family where the mother does all of the women’s work and the father doesn’t touch it. And Jon was raised to see certain things as women’s work and certain things as men’s work. Because of Jon’s disability, and the threat to his masculinity, I did really back off pushing that he do more of the laundry, cooking, cleaning things around the house.”

Sharon admits she’s a willing martyr, and points out that it was Jon who had gotten up at 5:15 this morning, this Fourth of July holiday, to wait in line for gasoline.

Once armed with a degree, Jon spent five months searching for a job. Northern Virginia Community College finally gave him a conditional contract for one summer of teaching, and has renewed it for 11 years since. He teaches both mathematics and physics. They think his difficulty in finding a job was outright discrimination and feel sure it wouldn’t happen again now.

Sharon: “He would be sought after by industry now. They would love to have him.”

Did you ever consider switching?

Jon: “Nope. I love my job. I really do.”

After moving to the Washington, DC, area, Sharon worked as a rehabilitation counselor for eight years. In 1976, when the Department of Labor was staffing for the upcoming Section 503 contract compliance enforcement, she applied and was accepted. She is now an employment opportunity specialist working in the area of policy and guidance in Affirmative Action for the disabled, for women and minorities and for Vietnam era veterans. She was named one of ten Outstanding Handicapped Federal Employees of the Year in 1978, and one of 13 representatives of the federal work force selected to meet with President Carter.

Do you think 503 is actually working?

Sharon: “Yeah, I think it really is. And I think the kinds of experience both Jon and I had in our initial search for jobs just simply would not occur now. First of all, people would be scared to not hire you without good reason, and I think they’ve had some pretty big attitude changes themselves.”

Is there reverse discrimination? Do us gimps have certain advantages?

Sharon: “Hmm. (Laughs, pauses) Yes. Definitely.”

How about depression?

Jon: “I was probably pretty bitter. Still am, in a lot of ways.”

Sharon: “I just knew that it was like novocaine; it was going to wear off. See, I knew it wasn’t permanent, so I didn’t have anything to get all upset about.”

Jon: “You live with it. There it is, and you gotta beat it. If you want to do anything, you gotta beat it. But you don’t have to like it.”

And after 14 years of marriage, how’s it been?

Jon: “There’s been ups and there’s been downs.”

Sharon: “We’ve had sort of the normal kind of marriage with a crisis a couple of years ago when Jon and I separated for 16 months. What was unusual about it is the fact that we did get back together.”

Did the wheelchairs put additional stress on the marriage?

Sharon: “When it gets to the issue of marriage, the disabilities aren’t what’s important. It’s the people. It’s who and what you are.”

Jon: “A lot of it is just working around whatever situations come up. And the disability’s just one of the situations. There’s a lot of other ones. It certainly wasn’t the disability that caused the separation or getting back together.”

Sharon: “The emotional trauma and the pain of the marriage breakup and the separation was far, far, far worse than breaking my neck and anything that I’ve had to live through with this disability.”

I think that puts things in perspective.

So does this: Both Jon and Sharon were very active in the National Paraplegia Foundation, and now the National Spinal Cord Injury Foundation, of which Sharon is a director. Do you feel a need to put something back into the network of disabled people?

Sharon: “No longer do I really feel that there’s as great a need to plug something back into it. But don’t forget that we were around when there wasn’t the legislation that we have now—I mean, somebody had to be getting some things done.”

Beverly Nameche#

Another car wreck, this time on a rainswept road to Boston: “I was waiting to see if my kids were alive, then I was going to decide whether I was going to live or die. And when I could hear, or was told, that they all were alive, then that was a very decisive point for me. Because I wouldn’t really have bothered. I think there’s quite a free choice there. To my right was a bright yellow light, really easy, really comfortable, and I could have just shifted over easily. Except on my left, I could hear my four year old crying. Now whether or not she was is questionable. But then I felt the tremendous need to pull to my left and to do the harder job.”

So it was that Beverly Nameche opted to raise her kids as a C6,7 quad. She doesn’t interpret the above events in a particularly metaphysical way, but more as a psychological state resulting from physical trauma. That was 1967.

Beverly was unlucky enough to begin her rehab at a general hospital in Massachusetts, and lucky enough to finish it at Stoke Mandeville in England. About the former she has very little to say, on the principle that if you don’t have something nice to say, etc.; on the latter she heaps praises.

“I spent eight weeks there as an outpatient and learned in eight weeks what I didn’t learn in about seven months in Massachusetts.” What she learned was to become completely independent. “It was excellent; very hard push. You’d arrive at 7:30 in the morning and have a tea break for a terrible tongue and semolina pudding or something, and if you could stomach it, you went on to the rest of the day. And left there at 5:30, green in the face because you’re so tired. They do not relent.

“I think rehab here in the States is really cream puff, at least the stuff I’ve seen. It’s about a two hour a day thing. Isn’t that ridiculous?”

It is ridiculous, and if that’s what you have now, you should know it. It is what most general hospitals offer. It is also worth noting that most American centers which are specifically in the business of treating SCI use Stoke Mandeville as a model for enlightened care. Most of them are hard push too.

Beverly continued her rehab by spending a year in Switzerland. “I thought that if I could go to another country and live and learn to drive a hand controlled car and bring up kids and deal with another language — all these unknowns—then I figured I could come back here and do anything I wanted to do.” What she wanted to do was to end her marriage, raise her children and move back into her old house in Gloucester, all of which she did.

The marriage had been rocky since before the accident, so there were no real surprises in its dissolution. She raised the ante on children by merging her mother-and-three-kids nucleus with a father-and-two-kids proton. Bringing them all up seemed like a pretty difficult undertaking, but nobody told her she couldn’t, or she didn’t listen if anybody did, so she went ahead and raised them. She encountered the most resistance over the house. Occupational therapists who looked at the house told her there was no way she could or should live in it, and she was so angered by their lack of imagination that she moved right in.

To be truthful, it doesn’t look like wheelchair paradise. It’s located about a block inland and upward from the sea. It’s an old rambling structure of two or three stories, depending on which side you view it from, and clings to and around boulders and outcrops of bedrock. It’s the sort of house some people worry about falling out of.

Improvements were made. An elevator was installed, not an Otis with a telephone, but a cheap industrial lift which works well. The driveway was paved up to the elevator door. A bathroom was added to the first floor, and a dining room and porch were converted to an open kitchen, living and dining area. The kitchen has counters at wheelchair height, a stove set directly into a butcher block, three or four knee holes for food preparation and dishwashing, a dishwasher, a side opening microwave oven and a grand view of Gloucester Harbor. She built a small sundeck, added vegetable and flower boxes, and gardens the steepest plot east of West Virginia. It’s an extraordinary house in an extraordinary place.

Lest it be thought that Beverly’s home is a monument to money, it’s not. Completing it was an eight year project attributable more to tenacity than to dollars. It’s a well loved house, and it’s seen five children grow up. And it’s seen some lean times.

“I’ve done some things for salvation, in order to keep the kids fed. I worked as a coordinator for three years on the Meals on Wheels program, which I started down here in Gloucester for elderly people, and I included handicapped people. That was just survival. I did it from the house and drove meals and got my kids to run them into houses and coordinated volunteers and ran the whole show.”

Much of her work has been closer to her interests. She was involved in a study on personal care attendants done by Brandeis University, then spent two years running the peer counseling for Tufts Rehab Center’s Independent Living Training Program. She’s just finished a four year term as a board member of the Boston Center for Independent Living and chairs one of the National Spinal Cord Injury Foundation’s regional satellite programs.

“I left the Tufts job because my Medicaid was taken away. I’d given up my SSI because I was making a huge $85 a week. Then the Medicaid went, and I just couldn’t afford to do that.” Sound familiar?

So now she’s moving toward sexual therapy. “I said Dammit, what’s one of the big questions anybody deals with after you say Can I walk? or maybe before you say Can I walk? Why don’t I pursue that if Mass Rehab will be so kind as to fund it?” Beverly’s very open to new ideas, her own and those of others. “I take it one step at a time. What I do next year isn’t what I’m going to do the year after.”

Beverly feels that new injuries are likely to receive rather unimaginative advice about their options in lifestyle and career choice. I asked her if she once felt that the expectations of others were being forced upon her.

“No, I didn’t. But I think that was partly because I was already married, was 33 years old and had kids. That’s different from what happens to the young person who is immediately hit with—Oh You Must Go to School— because there is no other avenue that anyone is terribly creative about. But it takes time before a person knows. I think it takes some maturing, some aging with a disability, before you get to the point of, Well this is what I’m going to do because this is what meets my needs. What’s different between that and an able bodied kid who’s going off to college and decides he wants to take a year off?”

Hot tip department: “I think it’s very important that people fill their lives as much as possible. I think sometimes right after injury, and right after leaving the hospital, you have to work at that. You have to think of things to do, you have to push yourself to get into things, to get out. I think I’m gregarious, but I have to push myself at times to get out and change my situation so that I meet new people and that I care about those people and they care about me. It makes my life fuller. But more important than that is that you have somebody to love and somebody who loves you.”

Through hard times and good times, the years seem to have brought a lot of compassion into Beverly’s life. How many years? She counts them mentally: “Why, it’s been 12 years! Time flies when you’re havin’ fun, doesn’t it?”

Bob Ludlow#

Santa Cruz is a pleasant coastal village trying hard to outdo Carmel in the charm and quaintness departments. Bob’s office is in an old, re-done section of the town, not pretentious, but carefully planned funk. The sign says Ludlow, Thompson, Fitzwater and Bolles, Attorneys at Law. Bob himself is friendly and athletic looking, nattily dressed in blue blazer, polka dot tie and button-down shirt. One of his colleagues looked in to ask why he’s so duded up today — it’s for his upcoming lunch appointment.

He drives a Mercedes, although he admits that compared to his old Chevy II, it’s a poor wheelchair car. Bucket seats. He has a home in the hills above town; very rural. Horse country. His wife, Sherrel, likes dressage. Their two kids like everything. It’s the American Dream. The good life.

Bob was 13 when he broke his neck on a water slide. C5,6. 1952. Since Santa Cruz had no rehabilitation facilities— had probably never seen a surviving quad before— Bob stayed home with his parents for two years, then shuttled between a general hospital and a rehab center in San Francisco for another year.

“The state of the art then was not anything like what it is now. They approach it a lot differently now. They lower the expectation level at the very beginning. They say, You have a devastating injury, you’re going to continue to be this way, you better get started doing something. In the old days, they’d say, Wait and see what’ll happen. They’d foster that feeling, then you’d have that extreme depression when you found out nothing was going to happen.

“Around 16 or so, I came back home after the rehab. My dad came in and said, Hey, a bunch of the kids are up at the pool and they want you to come out. I said, I’m not going to. I threw a temper tantrum, God, I cried, and he forced me to go up there and put me in the center of it. And my choice at that point was, continue to act like a punk or get into it. So I did it, and everyone said, Why don’t you do this, Why don’t you do that? And it became such a hassle refusing that I fell into it, I started flowing with it. And you know yourself, you don’t have any problem dating or anything else, because if you can adjust to it the other people around you can adjust to it.” He grins impishly. “That’s the way I handle it now, that I adjusted a long time ago and now I just have to wait for those people around me to.”

The rest of it seems relatively simple. “I got off (on?) my ass when I was 16 or 17, went to junior college for two years, went to Stanford (on a scholarship) and then I went to Hastings Law School so I’d have three more years to make up my mind what I wanted to do. I decided to become a lawyer, probably, after I’d gone to law school. I graduated in 1964, was with a law firm here in Santa Cruz for a year and a half and then I went on my own.”

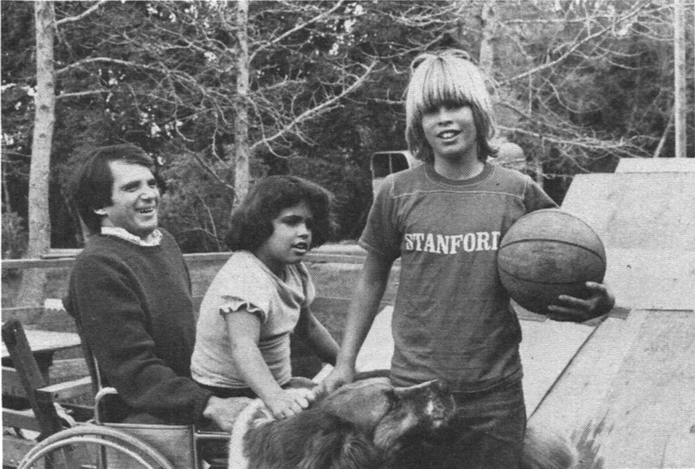

He’s been on his own, as an attorney, for 16 years. He and Sherrel were married 15 years ago and have adopted two children. Justine, now 10, is named from Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet. Tom, 12, more commonly known as Tigger, is from Winnie the Pooh, a classic of equal stature. The Saint Bernard is Gudrun, from Women in Love, and another less visible dog is Pooh Bear, another tribute to Milne.

Back in the office, I thought of George Hohmann and his epic struggle to adopt kids, and asked Bob if they had any trouble with adoption proceedings. None. He couldn’t believe that anyone ever had. He admits that his attorney’s manipulative skills, “people management” being the euphemism preferred by the trade, may have helped with the adoption board. “Basically, life is just dealing with people anyway.”

Bob specializes in criminal cases, personal injury, business and labor arbitration. Is the chair a restraint? Nope. He doesn’t believe the old saw that a disabled attorney prejudices his client’s case. The court rooms are accessible, and in Santa Cruz, even the jury box and bench have been made accessible.

He does, however, have a complaint. There were two young quads who once came to him for advice. They were both bright, so he urged them both to go into law. They did. Trouble is, they both hung up shingles in Santa Cruz. “Both of them came and practiced in my town. It’s no longer a unique experience for anyone in a wheelchair to be a lawyer.” His rueful expression is not for real— Bob is a ham.

He has built a credo, mainly derived from Dante’s Divine Comedy: “The worst place to be is limbo. Not purgatory or paradise, but the place where you don’t make choices. It’s extremely important that people not put themselves in limbo, because choices don’t hurt. There is no such thing as a mistake or a failure when you make a choice. You learn each time you affirmatively make a decision. I guess that’s the first thing you have to learn—that you have to make choices.”

And later on? “You have to re-establish your independence at some point in your life, because you get to the point—I don’t know about paras, but for quads — that it’s so easy to have someone else do it. Timewise. So you slip into that. Now I’m trying to get back away from that. I’m getting into doing more things myself again.

“Part of what I’m doing now is, I’ve decided to go out and live on my own for a number of months just to see if I can do it. It’s sort of hard to explain to my wife —it’s nothing personal—but that’s what I’m doing. And one thing I’ve found is, it’s not that difficult.”

Finding an attendant was a momentary concern. “You use someone for half an hour in the morning and half an hour at night. I think that subconsciously, going out and placing such reliance on someone was something that bothered me a great deal. But that anxiety you suffer in making that choice doesn’t really exist because once you do it you find out it doesn’t mean that much. The anxiety’s all over with. All you do is ask someone. The fears you have are not genuine. What’s really strange is that it takes only a couple of hours for someone in my situation to make changes occur that’ll make their whole life different.”

Now we’re back at home with the kids and dogs. Bob’s here too, running things while Sherrel’s on a trip to Mexico. Do the kids help with the work? “Yeah. I made a deal with them where we’re supposed to share it equally, so it isn’t a matter of just ordering them to do it at all. The kids’ idea of equal is different from mine.” Justine displays a chart outlining everyone’s chores: kids bring up wood, unload the dishwasher and clear the table. Dad gets to cook and wash dishes.

It’s not all one-sided. “The things I need done, the kids are really helpful about. Like in the evenings, when no one’s around, the kids’ll throw me into bed and make it a project. You sort of like that don’t you?”

Justine, in a fit of giggles: “I know. It’s fun. Singing around, it’s real funny. I like it. I like taking showers with you.” Justine is half kitten, half ham like Bob. She clings to him as he brushes her hair. “When I get dressed in the morning, it’s completely open. I don’t understand why people have this ethic —even if they’re not in wheelchairs —about getting dressed and taking showers and all that stuff, because these are all part of life with us.”

The place becomes a soundman’s nightmare. Justine is clunking around the wood deck on rollerskates and Tom is dribbling his basketball while doing one-handed wheelies in Bob’s spare chair. What’s Tom think about his dad being in a chair? “He’s still the same.” What’s the basketball team your dad’s going to coach? “The Santa Cruz Roller Coasters. I’m gonna probably be assistant coach.” Are you good enough for that? “Yeah, I know a lot. I can show you, shootin’ from a wheelchair.” He did. He also said he’d show me how he could go up two stairs in a wheelchair. I didn’t believe it until I saw it, when the method became clear. The two steps were separated by 30 feet of sidewalk.

Bob compares a SCI winner to Pangloss, in Voltaire’s Candide: “You’re foolish enough to think that it’s the best of all possible worlds, when it isn’t. It takes that kind of resiliency, a lack of cynicism, to the point where you can like people, you can like events, even if an objective viewpoint might say that the person shouldn’t like that situation. You know, it’s no fun being in a wheelchair, but it’s like the guy who goes in the service and he’s stationed in Paris, and he hates the service so bad he doesn’t like Paris.”

Final admonition: “Take a chance. Because they really aren’t chances. It’s a chance for success. There’s no chance for losing by taking a chance. There’s no way you can lose. If I were to talk to anyone who was thinking of a career, something to do, I’d say Do it. Just do it.”

Robert Heist#

This is not Rob’s first (or second or third) appearance in print. He’s the world’s easiest interview, and people capitalize on that. Young, articulate, likable, well placed in the business world and highly visible in his community, he’d be called an overachiever without his injury. As it happens, he’s a C5,6 quadriplegic. Rob so impressed Dr. Howard Rusk that his story serves as a forward to Rusk’s autobiography, A World to Care For.

It was a water skiing accident in the summer of 1966, just after he’d gotten his business degree from Tufts University. He was 21, and had an appointment to report to Officer’s Candidate School and thence to Vietnam. He broke his neck and his plans changed.

Rehab started at the Boston University Medical Center, four and a half months of it, followed by the same length of time at the New York (or University) Hospital Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine, more commonly known as the Rusk Institute. There he reviewed his vocational options, decided on the insurance industry and returned to the Boston area to make his way in the world of business. After applying to several large insurance companies, he finally settled on John Hancock and became a management trainee at $100 a week.

“I started the year after I got hurt and only three months after I was out of the hospital, so I really didn’t know what I was going to be able to do. I had the degree, but I didn’t know whether I’d be able to perform on the job. And they didn’t know either. So we figured we’d do this for a year. At the end of a year it looked good to both of us—I liked them and they liked me. So I’ve gone up through the ranks, done a lot of systems work and now I’m assistant manager of a unit of 72 people. In August I’m getting promoted to a systems job, as a systems analyst in the new business department, so things are working out well. Jobwise, it’s been terrific. It’s been a good 13 years.”

So much for a business career. Everything Rob does seems to be like that, done directly and efficiently, with no false starts. He needed to drive to work, so he bought a car and now drives 18 miles each way, winter and summer, between suburban Wayland and downtown Boston. He wanted to become completely independent so he worked at it for two or three years until he succeeded.

“To be able to do all the bathroom stuff, all the bowel and bladder routine, the dressing, the general food preparation, driving —it’s really important. I’m not sure I’d want to live alone, in fact I’m sure I would not want to live alone, because it’s a lot of work. I also know that if I had to, I could. And I have done it for extended periods of time.”

He became active in the New England Spinal Cord Injury Foundation, one of the two parent organizations now merged in NSCIF: “I’ve done a lot of work with the New England group, and a lot of that has been speaking to groups about SCI, about attitudinal barriers, people with disabilities, rehabilitation, vocational stuff, architectural barriers, the whole thing.”

For example, Rob feels that attitudinal barriers are largely a matter of people seeing the wheelchair more than the person who occupies it. People are awkward because they’re unsure of themselves.

“I try to get right out in the middle of the group, so they’re all around me, and then I say, Now this is maybe the first opportunity for you to look at somebody in a wheelchair and really stare and really get a good look, because usually when they’re kids their mothers tell them, Ooh, Bobby, don’t look. So I get in front of a group and give them a chance to look. I know that first, they’re looking at the wheelchair, but I also know that they’re looking at the person in the wheelchair. So it gives them an opportunity to sort of personalize themselves with someone who has a disability. It’s a good ice breaker.”

Recreation: Bowling in the winter and boating in the summer. He keeps his 17 foot outboard on Lake Winnepesaukee in New Hampshire. Although he needs help transferring from the dock, he drives the boat from a locked down wheelchair.

“The nice part about having the boat is that on summer days I can be with my friends all day long, and instead of sitting by the side of a tennis court watching everybody have fun, I’m right in the middle of everything. In fact, I’m supplying the fun. The fun is something that I’ve brought along, and people can swim off the boat, they can water ski, they can sleep, they can drink, they can relax, they can fish —there’s any number of things people can do from a boat and if a quad’s in the middle of all that, it’s terrific.”

Friends: “Relationships with friends are very important to everyone, but I think that people with disabilities tend to withdraw frequently from relationships that they’ve had or potentially can have, because they might feel inadequate or like they just don’t have anything to offer to the relationship. And that’s something that everyone with a disability has to overcome. Once they realize that there is a barrier there, but that there is something they can do about it, I think that’s the first step. And then they have to go about the business of deciding in their own minds that they do have something to offer and that given the disability and given the difficulties that are involved with the wheelchair and the things they can’t do, that they’ve got to key on the things they can do and the things that they can give to other people.”

And a final admonition: “A lot of newly injured people see films of paras and quads having a good time, going out in their own boats, bowling, doing wheelchair sports, having good relationships, and it’s almost like the pitch is Get a SCI and start enjoying life. That’s not where it’s at. It’s not that way at all. This all looks like a lot of fun, but it’s a substitute for what we all knew and enjoyed before. The notion that the SCI doesn’t exist is wrong. It is there, it is present, it’s something that somebody with a cord injury has to adapt to and adjust to and live with. And that’s how it is. It’s tough, but once you’ve sunk down low enough, then you can start to climb back out. And when you start to realize that you do have something to offer, then you realize that the fun and games are in fact enjoyable and rewarding.”

John Galland#

“I had a friend come to me in the hospital and he said, Look, I just came in to ask you, do you want the tablet? And this guy is real physical, and we used to do a lot of stuff together, and I looked at him and said, God, you almost understand, don’t you? It was really a very touching moment in terms of the empathy he had for the whole helpless condition.”

That’s about the way John was thinking when we first met in 1971. He had some strong scruples about doing himself in, but rather wished the accident had taken care of it for him. He acted wired —he couldn’t seem to articulate a sentence without popping a wheelie at the same time. Just another hyperactive kid from Texas.

I ran into him at Craig a couple of years later, and we recorded his thoughts on tape. The bitterness was still there, but he had become very analytical about his condition. In fact, he was so intelligently eloquent about why being paralyzed is less fun than the circus that his voice ended up as a major part of the soundtrack to Changes, the film I was working on at the time. Yet his whole psyche seemed somehow brittle, as if one part of his brain didn’t quite believe what another part was telling him. He was fighting something, and the fight was drawing down his energy.

Now, in 1979, we’re talking at my house. He exudes so much physical and mental health, I want to excuse myself to go do push-ups. He’s an extremely well person.

Gurdjieff, and others, have described energy as manifesting itself in three ways: physical, intellectual and emotional. While a few of us are wondrously balanced in our manifestations, most of us express ourselves most fully in only one of the three ways. John’s way is physical. That’s not to say that he’s intellectually or emotionally deficient, but that whatever he is is best expressed physically. And with John, it’s not just a need to be physically active, since a wheelchair marathon would satisfy that need, but it’s a need for risk. He’s a risk person. So am I, which explains why it took me so long to recognize it in John. Most of us aren’t. Risk is what makes John whole. Risk is what has made him whole.

John was always a righteous athlete. Whatever he did, he did as hard as he could. He tried to expand his limits in everything. In 1971, he actually succeeded in skiing through a tree, rather well above snow level, but it left him a T10,11 para. It was three days after his twentieth birthday.

After two weeks in Grand Junction, Colorado, and six months in Dallas, “I got up in a chair and was just freakin’ out, goin’ Boy, if this is the life afterward, give me the gun. I want it.”

“I said, Look something’s gotta happen. So they sent me up to Craig for a month and a half. Craig allows you your physical limits — whatever you want to do, that’s cool. And it’s really unique. Because I was goin’ down stairs in my chair, sittin’ on the floor and fallin’ over, and nobody minded. It wasn’t as if I was made of eggshells. And so I came away sayin’ Yeah! It’s gonna be alright.”

That was when I first met John, and I reminded him that he still wasn’t all that keen on the joys of paralysis.

“Right. It took about five years, and then the enjoyment began to return. I can go out and crash around in the woods and take a certain pleasure in doing things. I guess I lost the comparative reality.”

Comparative reality?

“Just the whole thing of always comparing yourself to what was, what you could do. Jesus, how futile that is. And I had to get rid of it. And the way I got rid of it was through crashing around.” John showed me what he meant by crashing around —he wheelied down the seven steps of my front yard for starters, did it again and splattered on the driveway, but was undamaged and undismayed —“You gotta learn how to fall” —then zipped down the steepest part of the hilltop I live on just for the hell of it. He takes wheelchairs where angels, able bodies and off-roaders fear to tread. “That was a real big attitudinal change, because it’s just suicide to keep comparing yourself to history. What does that have to do with anything now? You can bang your head against that wall only so long.

“After five years of hanging out and being high all the time, trying to run away from it, I finally got to the place where I was convinced I wasn’t all that fragile. You have to figure out what makes the difference for you. For me, the physical risk, getting out in the woods by myself — Like I said, I lost my comparative reality.”

More about risk. Since I expended most of my pre-accident energy on climbing mountains — difficult ones, sometimes previously unclimbed, often at ridiculous altitudes and latitudes —I was constantly asked about risk. Why should risk appeal? Isn’t risk the opposite of life? Why jeopardize what can’t be replaced? Well, I’m a veritable fount of answers, both corny and profound. But all you really need to know is that risk enhances the life experience for some of us. John is equally unwilling to get specific: “I can’t tell somebody with righteous fervor that this is the way it should be, because everybody’s a different case. And there’s nothing that you know for sure about anybody. That’s another thing that being in a chair has taught me.”

But for him: “In a physical sense, I’m much more whole, because I consider all the possibilities that I have and don’t limit myself. When I was a walker, I didn’t want to do a lot of things because they weren’t chic enough or they didn’t have enough mystique or they weren’t tough enough. And nowadays I’m not that way. In a sort of psychic or mental sense, I’m much more whole because I’ve got so much more perspective. One thing the chair has brought me is perspective.” Maybe you’re maturing? “Heaven forbid. No, I feel so much better now because I’m not a bitter, petulant little boy like I used to be.”

So, although John has not picked up his bed and walked, he has wheeled far into the wilderness. But what does he do in real life? He’s a professional student.

“I enjoy learning. I’d find a good teacher and study economics for two years. And I studied political theory for two years. I was a pre-med for a year and a pre-law for a year. So now I realize I’ve got 140 hours and no degree over six years.” Do they give a degree in becoming a renaissance man? “No, but that’s what I’d be going for.”

His present aspiration is to get a degree in psychology, because Texas needs help. He wants to form a private resource and service corporation to influence attitudes and legislation. “There’s a lot of folks in chairs in Texas who are not at all out. A lot of homebodies in wheelchairs, because there is so little information and a great suspicion of social services. A hell of a suspicion.” Why is that? “I think it’s because of the war. Not World War One or anything like that, but the Civil War.”

In the meantime: “I do some silver smithing, I live a simple lifestyle, and I eat lots of beans and rice and tortillas.”

Does he have a hot tip? Yep. Two of ’em.

“Plant your corn early. Sleep Dancer in the fourth.”