Lives IV#

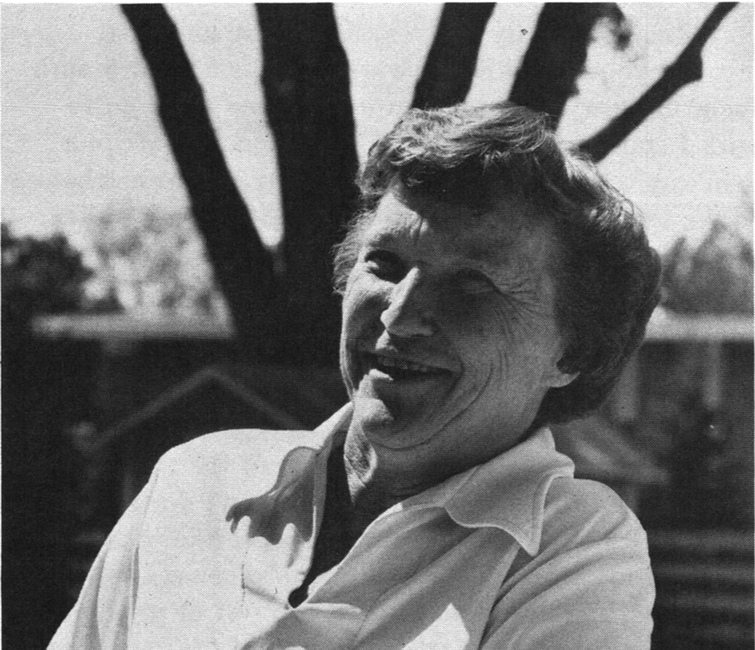

West Brownlow#

For years, some friends and I had a good deal at a swimming pool at the University of Colorado. It was called a kayaking course for the disabled. I was the token gimp, and my many “instructors” and I got to use the pool to run gates or practice Eskimo rolls or just horse around.

Then one day, this guy with a real fast wheelchair —you know, no brakes, no armrests, cambered wheels, nine-position axle, tiny casters, damped forks, spoilers —well this guy showed up with a borrowed boat, put a piece of packing foam in the bottom of the cockpit, braced his back against what looked like the side of an orange crate, and announced that he was ready to learn to kayak. His injury looked high to me, perhaps T2, perhaps too high for a sport which demands so much of the upper body. West didn’t know or care. Now, he’s a pretty fair kayaker. And he’s not T2. He’s C7,8.

Here’s West, about four days away from wheelchair or van, on the San Juan River. He got there by kayak.

After two years at the University of Vermont and two years of active duty in the Navy, what West wanted to do was ski. He became a Racer Service Representative for a prestigious ski manufacturer, did some coaching on the side, and, in 1973, broke his neck skiing at Waterville Valley, New Hampshire. He was 27.

He spent 10 days in Concord, New Hampshire, where he feels he got good care. They did a laminectomy, and he credits the resultant relief of pressure for turning what is orthopedically a C5,6,7 fracture into C7,8 function. He has good hands, good arms and minor dysfunction in his wrists. His doctor in Concord knew of Craig, and did a masterful job of convincing both West and his insurance company that that was the place to be.

For West, it was. “Immediately after my accident, I entered wheelchair sports. Then in the winter, I was exposed to basketball and I started doing that.”

West has become a wheelchair jock. In the world of wheelchair sports, he is a prime contender in whatever he enters.

“Wheelchair sports, for me, have been a Godsend. Sports are a big part of my life, competitive and recreational. Track and field events, basketball, archery, swimming, tennis, kayaking, scuba diving, sailing, flying, soaring … as the years progress, I’ve been searching out sports which don’t require that everyone be in a chair, because we live in an integrated world and I enjoy it that way.”

One of his more integrated efforts took place last April when West, Syd Jacobs, Hank Atkinson and I joined several AB’s for a five day trip down the San Juan River in Utah. The river was unseasonably high, the water viciously cold and the whole prospect of extended camping, 80 miles of seemingly treacherous rapids, and the logistics of coordinating four bowel programs caused visible apprehension amongst the new boaters. West: “I was, and this is an understatement, terrified.” The trip went well, and both West and Hank have since repeated the trip. Without the terror.

On the first trip, when West was presented with his wheelchair after a few days without it, he did wheelies and spins for about five minutes, just like a happy puppy rolling in sand. He likes his wheelchair. He was glad to see it. For me, the greatest part of a river trip is that I get to leave my chair behind, sometimes for weeks at a time. If I could physically do it, I’d kick mine to death at least once a day just on general principles. Not West: “This (chair) is a part of my body. I feel very friendly towards my chair. I like to keep it running at least as well as a Swiss watch. If it’s not running good, it feels bad. I wouldn’t want to be walking around with a limp if I could fix it just like that, and you can do that to your chair.”

What about modifications to the chair for sports?

“I would compare them to different types of shoes or boots —track shoes, hiking boots, running shoes, whatever. You have to set up your chair for the event. For basketball, marathons, everyday use, you set it up differently. It’s a revolution, and I’m glad it happened because it has opened all kinds of doors for what you can do with your chair.”

Basics:

Movable axles, normally to get the center of gravity forward. This shortens the wheelbase, so the chair pivots faster. Long distance pushers want to lengthen their wheelbase.

Cambered wheels. The wheels are wider apart at the ground than they are at the top. This provides lateral stability and a built-in tendency to turn.

Various casters. Small, hard rubber casters for basketball and other hard surfaces, larger pneumatics for fast outdoor rolling on all fours.

A Pandora’s Box of adjustments, including seat and back height, sealed bearings, instantly removable wheels, small diameter handrims, spiders, no-flutter caster forks and dozens more.

One of West’s modifications is for the twenty-six-plus mile marathon. He’s run several, including the Boston Marathon (he won his class, pushing in the rain), and uses a chair with an extended wheelbase and steering handles on the casters. For the downhill segments, he wears thick leather pads on the insides of his elbows. These are his brakes, since his hands are down stabilizing the casters. We filmed him on the Peak to Peak Marathon in Colorado, which wanders between 7,000 to 9,500 feet in elevation. “It is hard work. There’s a lot of uphill on this course, a lot more than I had realized. Sometimes you don’t even coast with each push. A big thing about the uphills is that it has removed every slightest ounce of guilt that I ever felt in going past people (AB’s) on the downhill. I used to feel guilty about that.”

This course has a seven mile downhill stretch. “The policeman told us afterward that he couldn’t keep up with us after about 45 miles per hour on the curves. The first time, I was terrified. After you’ve learned that your equipment can handle the conditions, you can really get flying. It reminds me of downhill skiing, in your picking of the line, and the speed, and the position— you’re in a tuck and your face is about a foot and a half above the pavement. No, I’ve never crashed. (Knocks on table.) I have gotten air.”

Actually, West isn’t all hardcore: “One marathon, some kids were doing dressage alongside the course. I stopped for a couple of minutes to watch, because I love horses and love kids too. I figured, what’s two minutes out of three or four hours? You might not have the opportunity again. And taking advantage of opportunities as they present themselves is very important to me. There’s not always another chance.”

What else does he do? “Despite appearances, I do a little bit of work in investments and real estate.” He gives demonstrations at school assemblies, exposing kids to wheelchair sports. He is extremely sensitive to AB’s who automatically think wheelers are deranged or sick, and wants to present a positive image. “I feel it is my responsibility to educate the public. I feel that everyone in a chair is an ambassador.”

Parting shot: “People seem to feel they always have to discuss their problems, disability, this kind of thing. And life is going on around us. (He gestures toward a wooded meadow.) You know, there’s thistles growing here, there’s trees, there’s fun things to do. I mean, things are happening. Grass is growing. And we’re all living life.”

Mark Johnson#

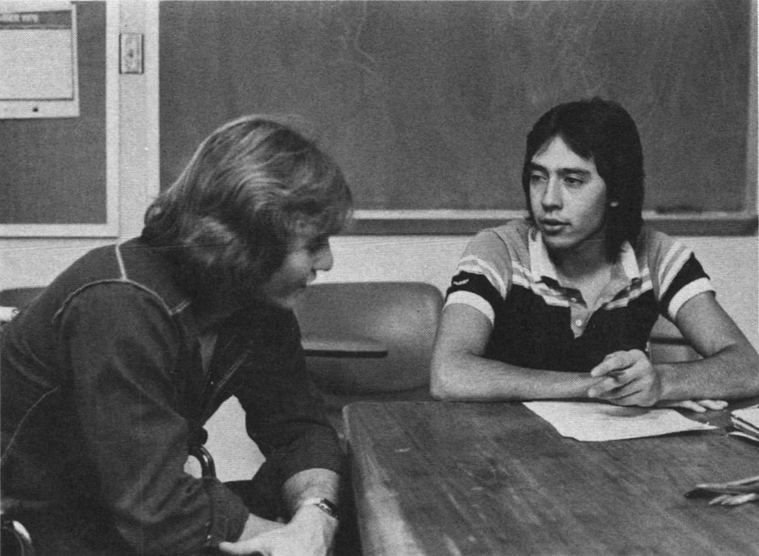

I first saw Mark at the 1979 NSCIF Convention. He was speaking from the floor, so all I could see was a frizzy head of hair and all I could hear was the most down home North Carolina accent imaginable. That’s what I need for this film, I thought, I need a good ol’ country boy. So I tracked him down and asked if he’d loan me his accent. He would, he did, and he’s about as down home as the President.

At the end of his sophomore year in college, Mark went diving instead of studying for his English exam. He distinguished himself, in the rarified world of diving injuries, by breaking his neck without hitting anything harder than water. He ran down the face of a rock quarry and did a shallow surface dive: “I just kind of coasted through the water and noticed I couldn’t move. Apparently I didn’t hit anything.” C5,6. 1971. 19 years old.

He spent two months in general hospitalization, three months at the Charlotte Rehabilitation Hospital, five months with his family and returned to school. DVR paid his, books, tuition and transportation. Later, they financed his van lift and controls so he’d be able to transport himself to work independently. Considering how frustrated others have been by DVR, I wanted to know how Mark had been so lucky.

“What I found out is how to play the VR game. And the VR game was to smile, be happy and lay down your plans to ’em. I’d just say, this is what I want to do. Here. Because by then, I started seeing it as a service I was entitled to. Heck, go out and break your neck, why not use it?”

Perhaps life does begin with spinal cord injury.

“That’s a good concept, really. It helped me realize that there were certain priorities in life. It’s a shame you have to be knocked down and kicked a few times to realize that, but I used to take stuff for granted. You know, I wanted to be taller, bigger, faster, stronger, smarter — you want those things, and all of a sudden you realize I’d like to be able to tie my shoes. I’d like to be able to clean my own fingernails. That kind of stuff starts to take priority.”

How about relationships with other people?

Before his accident: “I was always shy. I had trouble initiating relationships. I had more sisters than I knew what to do with.”

After his accident: “I’d say, Is a person just interested in me because I’m this horrible handicapped person? Are they interested in having more than just a verbal relationship? And so I got to playing games with myself. I’d say, Oh, they wouldn’t be interested in me physically. Ultimately I said, What’s the worst thing that can happen to you, Mark? Rejection, or not even trying to get your needs met?

“It took close to five years to finally realize that I wanted to get my needs met. I verbalized a lot of things: You know I’m paralyzed, you know I don’t have much sensation, or if you don’t know this, I’m gonna tell you. And I’m gonna show you. And I’m gonna reach out and touch you and I’m gonna hold you because that’s something I need to do and I want to do. And it’s worked.”

Mark came away from school with a bachelor’s in psychology, a master’s in education, guidance and counseling, and a lot more confidence. He applied for a number of jobs and was offered several.

“Then the hospital (in Charlotte) said Listen, we need somebody to do community stuff. And I asked, Do you see me doing this? Do you see me being able to do this? And they kept answering Yes. And what the position entailed was individual, group and family counseling, in-service education, staff consultation, community relations, goin’ to talk to groups about attitudes, doin’ all that kind of stuff, and I said, Hey, this is unreal. So they called me up, said Do you want the position? I said Yes. They said Do you want to know how much you’ll make? I said No, it doesn’t make any difference to me. I’ll take it. So I took it.

“The last three years, everything I’ve done, it just seemed like the perfect time to do it. Everything fell into place. I woke up in the morning, went and did it, and I said, Whoa, that worked out alright. Let’s try this. And then I just kept doin it.”

Mark is aware of the opportunity and the need to be a role model, both for the disabled and the able bodied. An exemplary gimp. A quadriplegic ombudsman: “I’d send people on errands back in the beginning years. Hey listen, there’s a curb there and I’m not gonna be able to get up it. Well now, if it’s a flight of steps and there’s something in that building I need or want, I’ll go there and approach the general public and say, Hey listen, can you assist me up through here? The visibility of it all— people say How did you get up here, and I say, I had about four people carry me up this flight of steps. It automatically sinks into ’em.”

Recreation: Mark is classified IA, which means he’s competing against the most severely disabled athletes, and he does it in the dash, slalom, obstacle course, shot, discus and javelin. He likes competing against people with similar motor function because it creates a fair field. He swims, plays table tennis, bowls, plays billiards and practices with the basketball team. The point is that recreation brings him a lot of personal satisfaction, and the way in which he recreates is unimportant.

Hot tip: “You gotta learn to laugh, you gotta learn to verbalize and you gotta be patient. Because it’s goin’ to take time, definitely goin’ to take time. But it’s all worth it.”

How long did it take you?

“It’s still goin’, and it’s been eight years.”

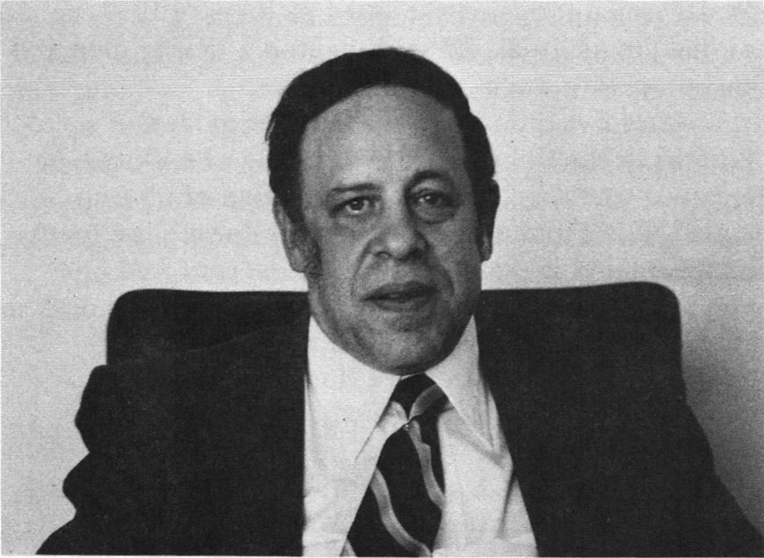

Richard J. Elrod#

Cook County, Illinois, is enormous. It has 920 square miles, including Chicago, and five and a half million people.

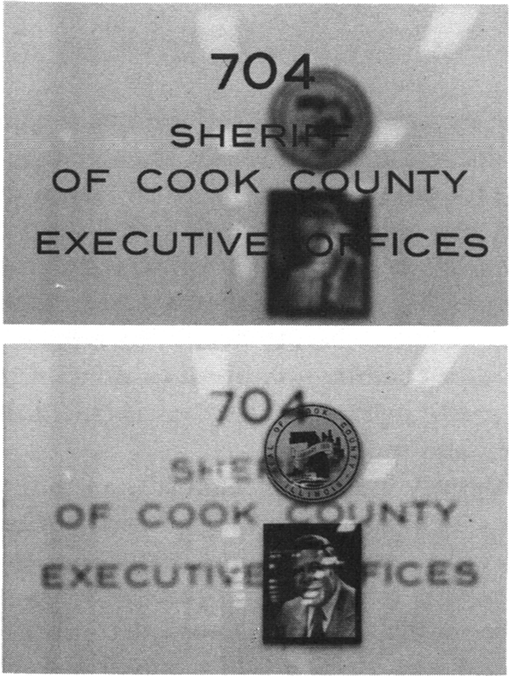

In 1970, and again in 1974 and 1978, the people of Cook County elected Richard J. Elrod as their Sheriff. He is, and was before his first elective term, a C4,5,6 quadriparetic.

I was nervous about this interview from the start. I knew that Sheriff Elrod had been injured in a civil rights demonstration in 1969, kicked by a hippie or a yippie in fact, so I thought that he might spot my rather obvious sixties sensibilities and hold them against me. When I found out that the interview would take place in the Richard J. Daley Building, I thought he might simply hold me forever. When I was told to drive into a basement security area and meet a deputy for escort, I very nearly bolted. As I wheeled past the guard at the elevator, past the guard at the outer door, past four secretaries lined up one after another, past a plainclothesman at the inner door (who turned out to be the Sheriff’s son), I was truly miserable. Having penetrated to the heart of the beast, I wanted badly to go home.

The first nice surprise was being admitted immediately. I’d always thought that making people wait was an accepted sign of professionalism in government. The second nice surprise was that very highly placed cops can be friendly, warm and responsive. Sheriff Elrod quickly confessed that he had no idea who we were or what we wanted, offered to help us in any way he could and proceeded to give generously of his time and talents.

It turns out that, in the sixties, Sheriff Elrod went to a lot more demonstrations than I did. As Chief City Prosecutor and Legal Advisor to the Chicago Police Department, he went to them all. When the Weathermen triggered the Days of Rage in 1969, he was on the job as usual. He tried to stop a fleeing man and ended up with a crushed C5 vertebra.

After five months at a general hospital and seven months in the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, he regained useful but incomplete function of all four limbs. He seldom uses a wheelchair, doesn’t use braces or splints and is ambulatory with one cane and one modified Canadian crutch. As he sits behind his desk in an upholstered swivel chair, the only clues to his disability are a crutch on the floor and somewhat deliberate hand motions. Mostly, he looks like any executive anywhere.

At the time of his accident, he was already slated to run for the Sheriff’s office. What’s remarkable is that, in spite of 10 months of hospitalization, he stayed on course. He campaigned from the hospital and won the Democratic primary nomination. As election politics warmed up, he put in full days of therapy at RIC, then spoke almost every night at a dinner, fraternal club or other gathering. It was part of his rehabilitation process. He first won election as Sheriff in November, 1970.

In addition to staggering law enforcement responsibilities, the Sheriff’s office employs 4,000 people and dispenses an annual budget of about seventy million dollars. Has his injury limited his effectiveness?

“The Office of Sheriff is a very demanding one, but it’s basically an administrative office. If you pick proper department heads and proper administrators, you can set the policy, you can see to it that you’re operating within the parameters of your budget and you can go out and see the people as often as possible. I must make three or four speeches a week. It’s a large county, and I believe that as much as I can be out, I am out.

“I spend 10 to 12 hours a day in the office, in addition to being out. I think that having had this injury, and being handicapped, actually helps me run a better office because I can put in more time. I don’t have the diversionary aspect of wanting to go out and play golf, or handball, or touch football or skiing. This is my job and this is what I’ve devoted my time to for the last 10 years.”

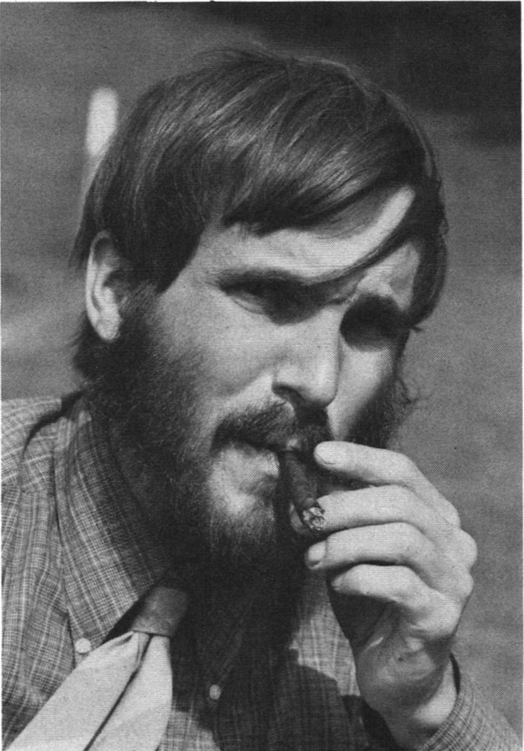

John Breasted#

He’s a journalist, and looks the part. Chinos, checkered shirt, loosely knotted striped tie, pockets full of pens and pads, and a constant conflict over whether to smoke a pipe or a cigar, neither one of which stays lit.

When he was 19, in 1967, John had a skiing accident. He collided with a tree, the tree won, and he is now a T8,9 para living in Hartford, Connecticut. Somehow, by coincidence, by plain bad luck, by professional malfeasance, by his own indulgence and that of others, by getting caught in institutions more oriented to sickness than to health, by a lot of lousy advice or by a combination of all or none of the above, John got pretty messed up after his accident. More, and for longer, than most of us.

He’s fiercely intelligent, almost the proof that brains are a liability in this SCI business. Whatever happened to him is clearly not a result of a lack of moral fiber or determination, because he has met, face to face, the most fearsome demons that any of us encounters in life. He is brutally honest about his experience, not because he likes talking about it, but because he knows that a lot of others are just as depressed as he was. He has reviewed this profile and has agonized over authorizing its publication. His permission is a courageous and generous effort to help.

After six weeks of stabilization at a general hospital in Denver, he flew to New York to be closer to his family. “I was at (a New York rehabilitation center), initially, for nine months. Then I went back for three more months within a few weeks.”

Complications?

“No, I was scared of the outside world. I had no physical reason to go back. The attending physician felt it was appropriate to take me back just as a kind of shelter.”

Even before his first discharge: “I can remember valuing the protection of the hospital more and more as the date of discharge drew near. I learned afterward that there are a lot of people who went through the same thing. They were very afraid to leave. Some of them were scared out of their minds with it.” And John’s timing was off—he got hit hard by a broken love affair just before he left the hospital.

“One of the things that’s most disturbing to males when they get hurt is the relationship with women — intimate love relationships, erotic relationships — and it certainly was to me. As a 19 year old who’d never had intercourse, it was very disturbing to wake up numb below the waist. I felt very cheated. And then to have the first woman that I slept with be someone I met after I was a paraplegic and then have her jilt me…”

He learned to drive, went to live with his sister in Manhattan and went part-time to Columbia. The University was inaccessible, the courses too technical for someone more in tune with his emotions than his intellect, and “It was too much to bite off, too abrupt a transition and scary as hell living in an apartment. Plus everything was so scary about Manhattan.” And the experience with his first woman nagged a little too much. Hence the headlong flight back to the rehab center.

The center couldn’t do very much. They’re in the rehabilitation business there, and psychiatric care for the severely depressed is something else. John’s doctor referred him to a psychiatrist “who runs this crazy operation in Pennsylvania. I spent seven months there, in residence in a house that my parents rented at great expense, and supposedly the shrink’s supposed to come in and see you every day. And this is the way he, successfully I gather, several decades ago treated real far-out schizophrenic cases. Well, he’s trying to apply it to just plain ol’ depressed people like me. At that point, I was so depressed —after a while you’re just willing to try anything and you kind of let people push you into things because you’re trying to get other people to make decisions for you. That turned out to be disastrous.”

The famous psychiatrist quickly delegated his duties to a junior psychologist, the place was a battlefield of petty jealousies and haggling, and life there was not serene. “I got increasingly desperate there. I attempted suicide. At that point, they didn’t want anything further to do with me because they weren’t equipped to handle overtly suicidal behavior. I mean, they just dumped me on my parents and my sister. They called up and said, You come down and get this kid. We can’t handle him.

“I went through over a year of really severe depression after losing that girlfriend in November of ’67, before I was able to function as a paraplegic in any kind of meaningful way in the outside world.”

Was there a turning point?

“I would say it was another hospitalization. My parents didn’t know what to do with me, and they called a neighbor of ours who’s a registered nurse with her head screwed on right. And she said that they seemed to have a good psychiatric service at Yale-New Haven Hospital and why didn’t they call them up? That was a good move. Yale-New Haven turned out to be a place that helped me out a lot, and I was able to pull out of my depression there.”

He spent four months at Yale-New Haven. Then the turning point wasn’t some sort of cataclysmic awakening?

“It was not an event or any one relationship. It was a day by day re-emergence into the world through many relationships and the support of the treatment program. I was able to come back home by late May, on passes, and then in June for good, to live at home and work as a laboratory assistant. I enjoyed the work enormously.

It’s really gratifying, once you do emerge from the period of depression and uncertainty and feeling, How am I going to make it in a world which I used to hike and walk and run in? Once you start feeling powerful and competent in that world, as a disabled person, it’s a great thing.”

Quickie 10 years: He returned to college in 1970, enjoyed it and graduated in 1972. Spent two years in medical school, lost another girl friend, had trouble with both his bladder and school and took a leave of absence. He “floundered” (his word) around Hartford for a couple of years. “In between leaving medical school and starting working for a newspaper three years ago, I worked for an insurance company part-time and did a lot of volunteer work for the medical school. And I bounced in and out of two psychiatric admissions.” Why the admissions? Bad times. It’s been a long road. “During the second hospitalization, I started working at journalism again, something I’d always done in high school and college and everywhere, but I started to think about doing it as a central activity.”

What does he do now? “I’m not a salaried reporter. Never have been. I’m now working as a freelancer for a neighborhood paper. I did work for two years for another paper, a weekly called the Newington Town Crier. I was really full-time there for a year, but my official status was as a freelancer.”

Can you make it as a freelancer?

“No. I can’t now. Very few people can. I’m fortunate to be subsidized by my family while I’m still doing it. The Social Security people called up and wanted to know what I was earning.” When he told them he earned about $30 a week for 30 hours work, they said to forget it.

Is he a gimp rights activist? Well, after a fashion: “An issue that’s important to me, as a 12 year paraplegic now, is violence. Of all kinds. I think that prevention of violence is a great way of preventing disability. Disabled people should be concerned about preventing war, as well as tooting in the legislature for the rights of the disabled. I don’t think people who just concentrate on ramping curbs and getting better veterans’ benefits are being socially responsible in limiting their political activities to that kind of thing. Another thing I feel is important in preventing disability —and I think that freshly injured people could and should be aware of it because they could go out to help prevent it from happening to other people —is that we need to teach people how to assess risk and how to go up close to injury but stay safely this side of it. The automobile is the third thing. Prevention of disability through automobile accidents is, in the US, statistically more important than either war or sports. I’d like to see disability prevented on all three fronts.”

How about human relationships now? “I felt until 1976 that life wouldn’t be very tolerable for me without that kind of crazy version of erotic love that we’re taught is supposedly standard for everybody. I’ve gone through a big change in my attitudes towards that.” He finds now that he can spread his friendships more diffusely, to more people, and feel comfortable with warm and affectionate relationships with many people from many parts of his life. Old friends, new friends, school friends, work friends, neighborhood regulars (of which he’s one), and, especially, the Quaker Friends Meeting. He joined the Quakers two years ago and likes what it has done for his life.

John talks a lot about the support he gets from his neighborhood community, both physical and emotional. “You get to see your neighbors here, there’s a lot of face to face contact and you develop rapport with them right away. I can go right out the front door and I can see neighbors, have conversations with them, feel supported and go back and not feel isolated.”

Does he feel that it’s important to make himself highly visible in the neighborhood? “I guess it is, just by definition, or I wouldn’t be doing it. I don’t do it consciously, to get out and be seen. I go out because I want to go out. But it sure is important to me, as a side effect, more than as a goal, to be seen as someone who’s out rather than someone who’s closeted away to be pitied. But there was a long time there years ago, where it would be hard to say which was the motivation. It was hard to do at the time. Yeah. Very scary.”

Andy Lopez#

Andy Lopez was a 17 year old into bikes and speed, a whiz kid with very winning ways at the local motocross and dirt tracks. He spent every warm weekend either racing or out riding with his buddies, usually on the maze of motorcycle trails the Forest Service maintains though the Rampart Range. To Andy, dirt riding was a passion, a way of life. It was what you did every Sunday.

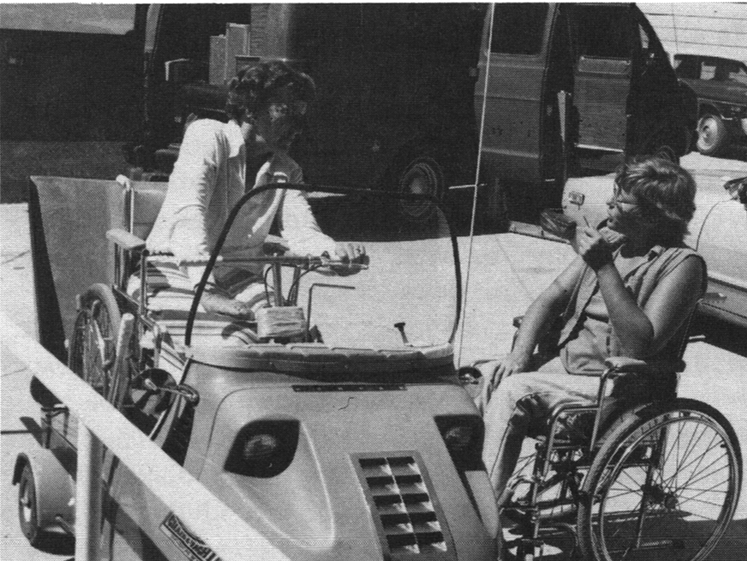

It still is. Since his auto accident in 1975 (T4,5), Andy still haunts the foothills, sand washes and back roads with his biking friends. He does it in a dune buggy.

I always thought a dune buggy was some kind of lumbering all-terrain vehicle, or a crawling lunar module, or maybe a cute little minicar with a fringed canopy and built-in coeds.

Here’s a dune buggy.

It’s a Honda Odyssey, hand controlled, available from stock in any large city. Andy wasn’t entirely satisfied with the factory model, so he shipped the engine off to California for a Honda-approved custom hot rodding job. When it came back, it was a pretty mean machine. It’s extremely fast.

“You have to go fast. That’s something in me, I’ve always had in me. I got this dune buggy and I want to go faster and faster and faster! It blows some of my friends’ minds.”

I asked Bob, one of Andy’s dirt friends, if Andy slowed him down: “Him? He keeps a pace that I have to keep up with.” He went on to tell me that all Andy’s friends had tried driving the buggy, but nobody was good enough at it to make it perform. It’s not like putting training wheels on a motorcycle; it’s a skill unto itself because all the weight is on the rear wheels and there’s no effective way to steer except with engine power. Andy’s got the touch and it does blow minds.

He’s also rolled it. He wears a complete racer’s chest harness and ties his legs in, so he wasn’t hurt. Is it dangerous? “Yeah, I suppose so. Everything’s dangerous.”

I noticed that Andy used a thin cushion on the bucket seat, and asked about weight shifts and the possibility of pressure sores when bouncing along a rough track at 60 miles per hour. I was informed that since the machine has no suspension and is air-borne most of the time, it is a weight shifter. Oh.

“There’s a certain feeling about being in the dirt. There’s no law, no stop, no go. Just do your own thing, which I’m into.”

Dirt rider outlaw? Not entirely. Since his accident, Andy has completed his GED and two semesters of college. He goes to school two days a week and works at Craig Hospital the other three.

“I’m working with data research and interviewing patients, finding out what they’re paying pre-admission to Craig, what hospitals they’ve been at, then we do follow-up on them when they come back to Craig.”

He’s good at his job. People obviously feel at ease with him, and he seems like anything except a social worker. That’s a compliment.

A few one-liners:

The wheelchair: “My biking friends love my chair.” (They tear it up playing with it.)

Rehabilitation: “You learn something every day. Something’s hard, you keep doing it and it gets easier.”

Hot Tip: “Stay active, don’t stay at home, just keep moving.”

Speedy Andy Lopez, dirt bike outlaw, moving target, was last seen vrooming off toward a master’s degree in sociology.

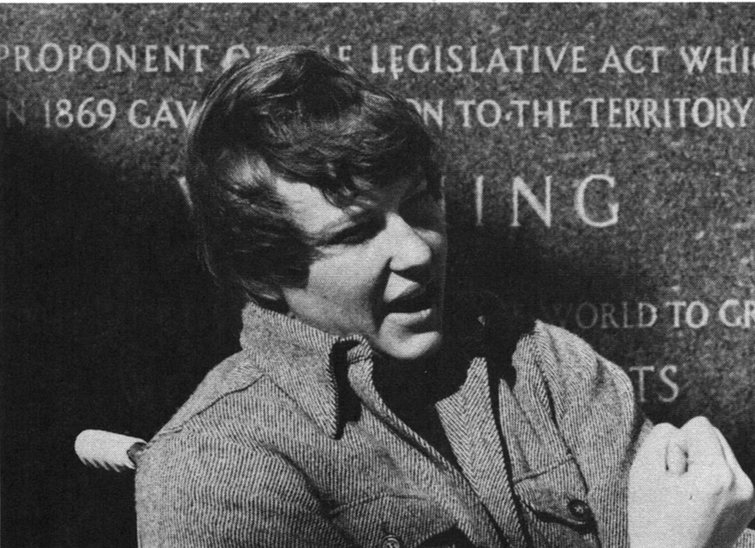

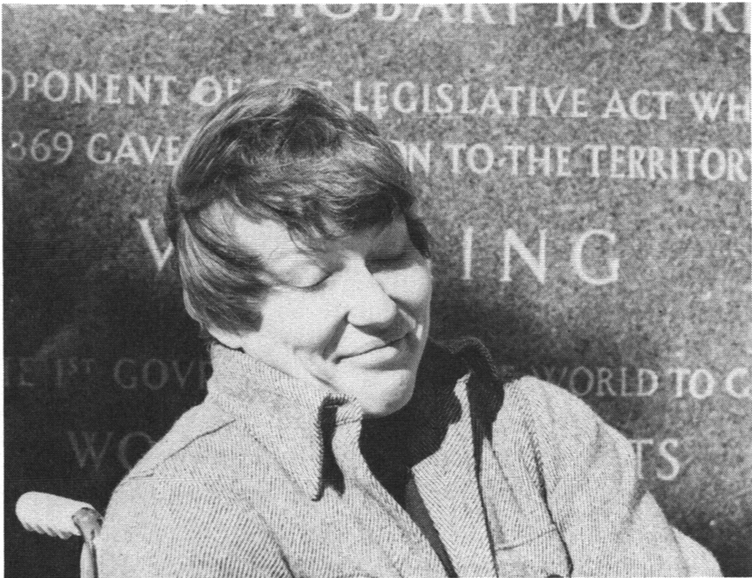

Lyn Dickey#

How’s this for a resume?

“When I first came back to the state in 1974, I went to work for the Powder River Resources Council, just a group of ranchers in the northern part of the state trying to keep the coal development in that part of the country under control. I did that (read, she ran that) for three years, then I took a short summer job doing some water research for Senator Malcolm Wallop, who had just been elected from Wyoming at that time. And from there I came down to Cheyenne and went to work for Governor Herschler as the director of his Energy Conservation Office, did that for a year and a half, and now I’m working as his legislative liaison. And as soon as I’m through with this session (of the legislature), I’m planning to hit the road and just travel for a few months.”

She forgot to mention that the governor also appointed her to the Environmental Quality Council, which oversees all the state’s environmental laws. Not bad for a hometown kid from Buffalo, Wyoming.

Back to 1966, when Lyn was 17. She was in a car wreck which left her a T8 para and her mother a quad. When I made the mandatory comment that some people had all the luck, she conceded that it was a major experience for the entire family.

Lyn was pretty beat up, so she cooked up a few projects to pass the time while she was recuperating. She finished her junior year of high school by sending recorded tapes back to her teachers in Buffalo. She also launched a political career.

“I tape recorded a speech of all the reasons they should elect me student body president, and they played it at the assembly where all the other candidates gave their speeches. Sympathy vote didn’t make it, though; “I came in second.”

She spent the summer at Craig Hospital, and, come autumn, was back at her old high school in Buffalo.

“The Johnson County High School has about seven levels, with worlds of stairs among all the levels. So all the football players in my class—they loved it — there were contests to see who could get me up and down the stairs the fastest. They would run up and down the stairs, which is probably why I have not the least qualms about being hauled up and down stairs by much of anybody.”

She graduated, worked in a local bank that summer and went to the University of Illinois. She graduated as an English teacher, a profession she hasn’t really exercised, and went through a second spinal fusion and an aortic repair somewhere along the way.

Lyn’s first career decision was to get into some sort of voluntary service, so she asked VISTA and the Mennonite and Jesuit voluntary services. “The Mennonites were the only ones who seemed to feel, like, they’d never had anybody in a wheelchair before and didn’t really know what I could do, but they figured that if I wanted to try it, they’d take me. So I moved to Wichita and worked for a year in a house full of other volunteers.”

In addition to serving as receptionist, secretary and fund-raiser to the voluntary service, she worked on a few other interests:

She taught adult education at night for the Wichita school system.

She organized the Wichita chapter of Common Cause.

She fought a nuclear power plant, and won.

The Mennonites may think twice about their next gimp.

Her next decision was to move into citizen action, so she paid Wyoming a visit before heading to Washington, DC, which is where she figured citizens went to get active. But fate, or whatever, delivered her to a board meeting of the Powder River Basin Resources Council, whose only staff person had just quit.

“So I figured, why go to Washington DC? These guys need some help. Convinced them that they should hire me, and just fell right into it.” And so began the five year saga of Wyoming’s enfant terrible. The rest is not history, for I suspect that Lyn’s upcoming sabbatical is simply the calm before the storm. In the meantime, here are some glimpses of whatever it is that makes her tick so dynamically:

Did the governor first appoint her because she was a woman? “Doubtful.” Because she was a paraplegic? “I don’t think he even knew it.” She goes on to say that she thinks she was appointed because she was perceived as being a “reasonable radical.” Huh?

Once Lyn had the Energy Conservation Office set up, she grew restless with the job because it was primarily educational and “because there were no real political fights going on, and I miss the head-butting.” So…

“I got the governor to hire me to be his legislative liaison for the session. Plenty of fights here. And the legislative session surely is a time when you’ve got plenty of dates certain— you’ve got a battle that has a time when it’s won or lost.”

Here’s what a legislative liaison person does: “See that the bills he (the governor) wants to have passed are moving through the process as best they can. Letting him know where they are, letting him know who’s taking what position on them, getting information to the legislators at his request or at their request — basically, just to track the legislation for him.”

But… “It has not been nearly as satisfying a job for me as lobbying for Powder River, because there’s no identifiable constituency. You just have the governor and you have, theoretically, all the people in the state.”

She has an interesting sense of context. Here’s what she feels about her accomplishments of the last five years: “I have attempted to influence the political history of the State of Wyoming, and I’ve probably had an influence on it. I’ve spent the last five years of my life basically trying to help keep some controls on the growth of the mineral industry in the state, and yet for all I know, it might have been far better if I hadn’t done that. The best thing in the world for getting things back to a degree of sanity in this country might very well be to just continue the exploitation as fast as you can and with as little thought as you can so that you reach the critical point sooner and everybody can turn around and head in the right direction. I think that people who feel they are influencing things in the direction they seem to be influencing them, they may be right and they may not be right. It’s just a way to spend your time. Really. Everybody has to do something.

“I want to be sure I keep my grounding in the things which I think are truly important, which have nothing to do with energy or politics, but with just living and sharing yourself with people and being there.”

Lyn obviously knows a great deal about dealing with people, but she’s not immune to the reactions of others to her chair: “Everybody you run into, the first thing they notice about you is that you’re in a wheelchair. There are people who don’t get over noticing that as being the most important part of you. And these people —they’re simply people you’ll never get to know. I think that’s true of most any individual. Some people can’t get over the fact that you’re bald.”

Her work requires her to do an astounding amount of travel, which she loves. I asked her about practical problems: “I think it’s downright handy to have a catheter in you when you’re spending a lot of time on the road, because you can just pull over and hang your bag out the door. Now on an airplane, it’s much more difficult, it’s true. There’s no really acceptable way to go to the bathroom in an airplane. When it becomes necessary for me to, I simply pee in the throw-up bag and ring for the stewardess. And none of them ever seem to object, to tell the truth, but I find it somewhat embarrassing.”

And about the Privilege of Paralysis: “A lot of times you’ll get asked to move to the front of the line so you don’t have to wait, when obviously you’re better equipped to sit in line than most of the people who are standing up.” Cops are nice to her, and although she’s been stopped numerous times, she’s never been given a ticket. “I’ve always felt that the first cop that has the guts to give me a ticket when I’m speeding, I’ll be forced to congratulate him for his courage.”

Update: Lyn, when last seen, had just been given a ticket for speeding. She did not congratulate the patrolman. She was leaving the next day to lobby for Powder River in Washington, DC.

Imogene Dickey#

Buffalo, Wyoming, is a three-stoplight town on the east flank of the Bighorn Range. It’s an old town with wide, shady streets, gracious houses and the beginnings of the energy boom starting to show around the edges. It’s still the kind of place small town lovers love. We’ve come to the home of Will and Imogene Dickey, longtime residents. There’s a ramp in the back, a beat up VW bus with a lift and a Chair-E-Yacht. This last is a powered trike which will transport a wheelchair and its occupant. It’s designed and manufactured in Shoshoni, Wyoming, a town lots smaller than Buffalo. And best of all, Lyn Dickey is here on a visit. Her story precedes this one.

As previously reported, the Dickey family won the paralysis sweepstakes back in 1966 when a car wreck left mother Imogene a C5,6 quad and daughter Lyn a T8 para. Imogene was 42 then, with four children. From her account, the accident was hilarious…

“We just did the old roll, three or four times, and she and I ended up under the car. When the wrecker from Gillette came out, finally, to lift the car off of us, it just got the winch hooked up and was out of gas. I always thought that was neat. The wrecker ran out of gas.”

Were there any guilt feelings about the accident? Lyn: “Everyone felt guilty. I always figured I was the only one who felt guilty, because I was driving. I didn’t find out ’til years later that Mom felt guilty ’cause she decided on the route, Dad felt guilty ’cause he didn’t go, and (brother) Dave felt guilty ’cause we were coming down to see him. A friend felt guilty ’cause she had had a dream the night before that we were gonna wreck, and she didn’t tell us…”

Imogene: “But I tell you, the guy who took care of that was Will (her husband). He said to forget it! You don’t do anything but use up a lot of energy and make people miserable, worrying about what you should have done. There’s no way to go but up. And the more time you spend dwelling on things that might have been, the less productive life you’re ever gonna live. And Will just got that across to Lyn and me both.”

Lyn: “I think it’s true that Dad was instrumental. He always had taught us, and continued to teach us, Wherever you are right now, that’s where you are. That’s what you deal with.”

After seven weeks in a general hospital and five months at a SCI unit, both were back home in Buffalo. While Lyn was being run up and down the many stairs of her high school by eager football players, her mother was having a different experience.

Imogene’s first challenge was being mother to four children, one of whom was a paraplegic. “The biggest thing was frustration. Absolute frustration. In the morning, when the kids would all get off to school, I’d come to this kitchen door and see every conceivable surface covered with something. I hate clutter. I have to have a neat place to have a neat mind. So I got in the habit of backing in so I couldn’t see it all. I could do it, one thing at a time, but if I had to look at it all, I couldn’t see how I could ever make any order of it. So I just backed in.” (Maybe that’s how we should all approach our injuries: Back into coping. One thing at a time. The parts, taken singly, can be less than the whole just as the whole can exceed the sum of the parts.)

Their doctor’s wife intuited that Imogene’s return home might be a difficult time. “So she had this bunch of gals, about 10 or 12 of them, and every day one or two of them came in. Each morning. Not to work, necessarily, but just so I’d be up and in here and talking and living. And they did that for years. I feel like I have the greatest bunch of people around in the world.

“You expect your family to rally around and be what they should be, but your friends are the ones that keep you going. They expect you to do things, and you just don’t want to disappoint them. You don’t really have any choice. You either roll over and play dead, or you stay in the swim of things.”

Buffalo winters are cold and deep. How does she deal with below-zero temperatures and all the snow? “Everything I belong to, as much as I can, I ask them to meet here in the winter. It works out well. So I have Musical up here a lot, PEO, anything, any committee I’m on, Republican Women’s Club meets here regularly, and that’s great because that way I can stay active without having to go out a lot in the winter time.”

How about your church? “It’s as important a family to me as my own immediate family. I feel that a church home and a church family is an absolutely essential ingredient in my life. I feel a closeness to my church.”

Lyn points out that this kind of support, from friends, membership groups and church, would be less available in a larger town. It’s an interesting trade-off. So many of us have moved to the warm weather, the flat terrain, the accessible architecture, or just to be near a hospital or rehab center. Imogene has stayed on in a small and remote mountain town with vicious winters, steep terrain, few architectural amenities and only the usual rural health care. Although she didn’t say so in as many words, I think she’s decided that her roots are worth more to her than her convenience. In these mobile days of scattered friends and families, few of us can find our roots, let alone treat them with love and respect. There’s some nice values operative here. Yet Imogene does admit that spending some time in San Diego each year would go a long way toward tempering the impact of Wyoming winters.

Now that her four kids are out the door, and she and Will are once again the chief boarders, she’s written and published a cookbook, Recipes and Cooking Hints for Brides and Other Handicapped People. The title alone is worth the paltry price, and the recipes are what you make of them. Literally. Here’s a gem from the preface:

“I believe the shucking of false pride was one of the most difficult things I had to accomplish. Finally I accept that although I may not like it, one of my chief responsibilities as a physically handicapped person is to help able bodied people. Help them feel comfortable, help them feel useful. I have long known that the only truly happy people are those who are lovingly doing for others. So I do all I can, but try to accept help graciously for the things I can’t.”

The Joy of Cooking doesn’t have anything that good in it.

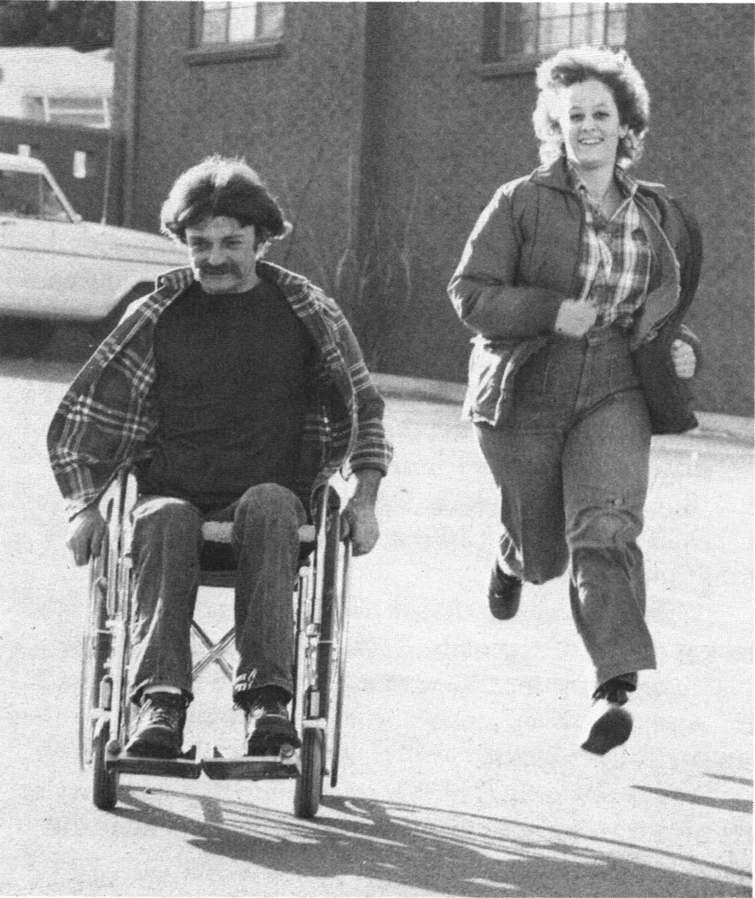

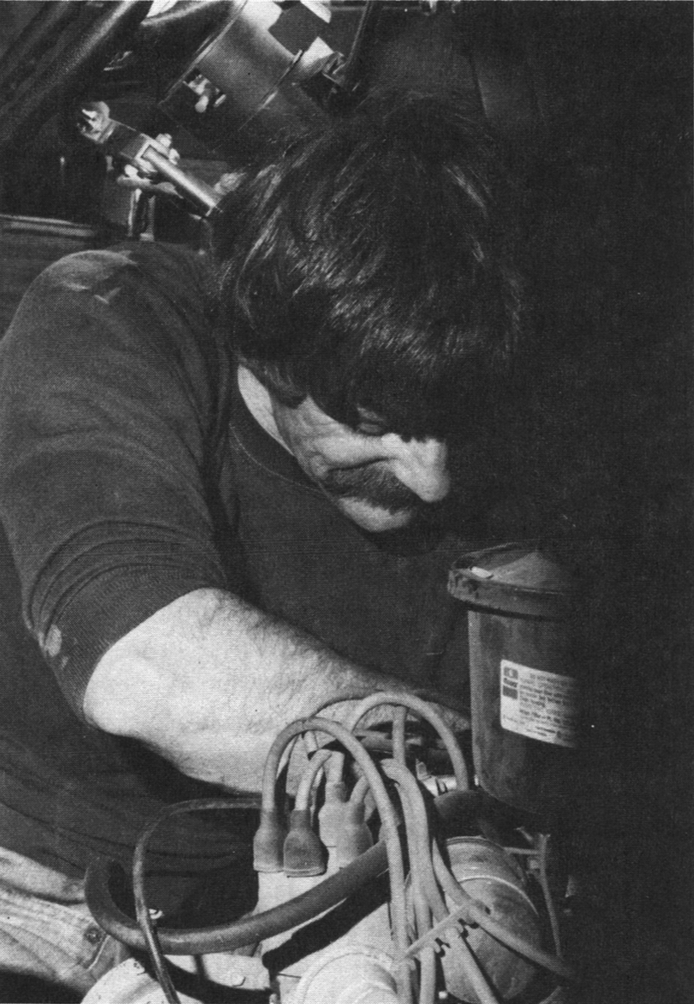

Bob Felker#

In 1968, Bob was 20 years old. He had a high school education, some additional technical and auto mechanics training and a Louisiana accent thick enough to cut. And after tangling unsuccessfully with a forklift, he had a broken back. He’s a T10 para.

Bob would be described down south as a good ’ol boy. He’s a wiry man, with deepset eyes that look at the world with a twinkle from somewhere way back in his head. I can never tell when he’s pulling my leg or being serious, and I usually feel that he’s doing both at once. His life is pretty good right now, but it took him a few years of searching, after his accident, to find his new self.

“The hardest thing was goin’ out into the real world after I was hospitalized for 14 months. During this time I never had any real interaction with the outside world —I was so used to the hospital type of setting and the other spinal cord injuries, other wheelchairs around all the time. Goin’ out in public by myself, goin’ to the grocery store, shopping, anything, just bein’ able to cope with the general public — that’s the roughest thing.

“I can handle it now. I just look at all the things I got goin’ for me, and depression doesn’t stand much of a chance of lastin’ very long.”

Bob was particularly self-conscious about his wheelchair. He didn’t like it, and he figured strangers didn’t like it either.

“I had to realize that if people do look at me, it’s probably out of curiosity. I like to think that maybe they’re admirin’ me. They’re admirin’ the things that I do. And I show off, pull a wheelie or somethin’, so they can really admire me.

“Kids are neat. They’re really innocent and they’re not afraid to ask questions. I remember one little kid asked me one time why I was in a wheelbarrow, and I thought it was funny and I explained it to him real good, sure did.”

As his dealing with the public became more skillful, he started working more energetically on personal relationships. Sex was a problem, and he dealt with it.

“At first I didn’t think I was capable of any type of sex, and I believed that if I couldn’t have sex exactly the same way I did before I was injured, in the ‘normal’ way, then it wasn’t sex. Now I’ve learned different techniques, different feelings, learned to recognize my feelings … my sex life now is better than it ever was, it really is.

“Met this girl, she really kind of turned my head around and made me realize what life was all about and how interestin’ it could be and how good it could be. For the last year or so, I’ve really been high.”

Bob now lives in a house by the foothills, shared by two paraplegics. “Won’t be livin’ there too much longer, hopefully, ’cause I’m going to be gettin’ married, get me a new roommate.”

Along with marriage, education is a high priority in his life. “I came up here from Louisiana with schoolin’ in mind, and that’s what I’ve been doin’ the last two years. Goin’ for my bachelor’s in human services and planning to do graduate work in rehabilitation counseling.”

What’s it like going back to school?

“It’s a bummer at first. After you been out so long, and of course goin’ to school with kids a lot younger than you is kind of a pain, too. But after the first semester you’ve pretty well got it whipped. It’s fun, it sure is.”

Bob may be on a winning streak, but he still needs to live until he gets his degree. He does this by plying his old trade, auto mechanics. He specializes in mobile tune-up jobs, but works on any part of a car that needs fixing. He’s earned a local reputation as a top notch mechanic. Like many of us, he faces conflicts with the Social Security system.

“Social Security is a real booger, it sure is. It destroys your incentive to work. I make $264 a month Social Security — that’s my total income —if I go to work I stand a real chance of losin’ this income plus losin’ my schoolin’. So I have to do this auto mechanics on the side to supplement my income in order to live, and I got to do it under the table.”

About his work? “I like it. I like to be able to say that I can do it. It’s kind of an ego trip and it also gives me a sense of self-worth. Lots of times an able bodied person’ll come to me and ask for advice or for my work. I may not be able to do some of the things he can do, but I can do some things he can’t do. I get enjoyment and fulfillment out of that. I like to see the results of my work, like all mechanics, cause I can see the results. I’m not goin’ to do it the rest of my life; that’s why I’m goin’ to school. I’m tired of gettin’ my hands dirty.”

Today, Bob has braces on and is draped over the engine of my ’73 Ford. He’s just fixed a post-ignition problem it was having. He stands up beside the car, looks at his hands, and delivers his manifesto:

“I’ll get me a degree, get me a secretary. I’ll let somebody else get their hands dirty. This stuff’s alright for amateurs, but I’m goin’ to be pro-fessional!”

Here’s a story Bob told: “About two or three feet high, the grass was, and I was sittin’ right in the middle of it in my wheelchair fishin’, and somethin’ started comin’ at me through the grass. And the way it was movin’, it looked like a big old snake, it sure did. Tried to turn around to get out of there, and when I did my front wheels fell in a hole and I was stuck there and this thing kept comin’ closer and closer —really gettin’ close. When it was about 10 feet away, I was so scared that I just made a superhuman effort and jerked my wheels out of the hole and got turned around and pushed all the way back to the road and this thing was following me all the way. It came out of the grass and it was a cotton pickin’ armadillo —big ’ol armadillo, as harmless —it sure was. So I tried to chase it and I was goin’ to get it and eat it. Sure was. But I couldn’t ketch it, sure couldn’t.”

There’s a moral here somewhere about snakes in the grass and things appearing scarier than they really are, but Bob would be the last person to bludgeon us with it…