Lives III#

Anna Absalom#

The house is green brick, situated in an old, well-kept neighborhood, and looks inhospitable from the front. Stairs. Lots of them. Around to the alley. Better. It’s pretty much like anybody’s back yard: parking apron, high fence with gate, trash cans and a path leading to another set of stairs. But there is also a door at the ground level, and Anna appears at the upper door. She’ll be right down.

She is. There’s the unmistakable whoosh of air that accompanies a descending elevator, and Anna asks us in. The room feels good in some vague way, although it is actually an afterthought created when Anna obsoleted her garage by buying a van too high to enter it.

The elevator is exactly large enough for the wheelchair, and I ride up first, sending it back down for Anna. This gives me a minute to take the place in. It is incredible. The elevator opens onto the kitchen: old brick, arched window lintels and a venerable drop leaf table that looks Quaker to me just because it’s classically simple and beautiful. That’s the old part. The new is a wheel-under sink and stove, lowered counters, raised oven and a dishwasher. All very modern, all exquisitely compatible with the surrounding antiquity.

Anna arrives and we move to the living room. There’s some principle of design and taste operative here that I don’t yet understand. I see three or four more pieces of extraordinarily honest and appealing early American furniture, including two Windsor chairs, in a room of light and openness. Instead of using limited space to show off lots of objects, she uses a few objects to show off lots of space. Bare off-white walls, bare wooden floors, yet not a trace of austerity.

If clutter is to be found in this house, it’s in the workroom adjoining the living room, and it’s very functional clutter. One entire wall is covered by a complete color spectrum of hanging yarn. A corner holds a large slanted work surface illuminated both by overhead spotlights and magnifying goosenecks. There’s a Scheffelaria plant to separate business from frivolity, and a spinet piano occupying the last available wall.

Upstairs are the bedrooms for Anna and her two daughters, also reached by elevator. Anna tells me it’s a pleasant open loft, and I don’t have to see it to know that it’s exceedingly pleasant. You could say that I liked Anna’s house.

Why, I wanted to know, did she ignore the splendid dissenting advice from the rehabilitation center and from experts, including me, to get this funky old three story relic where she had to build an elevator, for God’s sake, just to get home? Why not get a nice efficiency apartment with security, central air conditioning, wall-to-wall carpet and a four-by-six balcony with a view of more balconies?

The question is fully answered just by seeing Anna at home in an environment of her own making. But since we can’t all visit her, here’s why: “I’ve never lived that way. I didn’t want to start. My parents had bought this house as a rental property, and a friend of mine made a videotape of it and brought it to me in the hospital, and I said that’s it. I did look at some things that were on one level, but it would have been a lot more money and I didn’t see anything I really liked.”

Before her hospital discharge, she paid a visit to Gerry Winters, a quad whom Anna had been told had designed a really excellent house. “Just seeing her there was so inspiring because she had raised these four kids and she had this beautiful home and a good marriage and it was just really nice talking to her. Talking to her was the most influential thing that happened.”

So Anna got her funky three story house and found it to be good.

In 1975, a month before her thirtieth birthday, Anna became a T12 para when her VW beetle blew off an Idaho highway. Her second marriage was failing and she had two young daughters to care for. She had a BA in English, a California teacher’s certificate, part of a master’s in art history, a strong interest in ballet and, most important for her financially, she had received extensive training in the craft of weaving from a French Canadian master who had taken her on as a private student. She makes her living reweaving textiles, mainly oriental and Navajo rugs, and has been doing it for over 10 years.

“I never thought I could continue to do it for a living, but I have. It’s just worked out that way. I started working for a few dealers here in town, and of course dealers always have things that need to be repaired. And then I met a few collectors, and collectors always have things also. I mean, they’re always buying other things, and then they gave my name to friends. And I’ve done work for some museums here, and they give my name out. The other thing I’ve got going for me is that I don’t have a lot of competition. There aren’t too many people doing what I’m doing.”

Indeed there aren’t. “Reweaving” is not an adequate word for what Anna does. Her work requires a knowledge of dye chemistry, an understanding of many weaving techniques traditionally used by the cultures which originally produced the art works she repairs, and an uncanny ability to match color, texture and design. She’s very good at what she does and has all the work she wants or needs.

Then there’s another role, Anna as mother. Her quick shot about teenage kids is that they’re “real maddening.” But … “I wouldn’t have been able to move into this house as soon as I did and get everything going if I hadn’t had them here. And they’ve been really helpful. I guess that it’s a sign that everything has returned to normal that now, if something needs to be done and I ask them, they don’t always just rush to do it. In the beginning they sort of waited on me and acted like little nurses, and now they just act like normal unruly teenagers.”

Socially, she does about as much as she did before the accident, going out to dinner, movies or performing arts, or visiting friends. Intimate relationships are more of a problem for her because “People don’t know what to expect and they’re afraid to ask and they’re afraid to find out.” She has not run away from intimacy, just finds it a difficult subject that needs attention.

“Yes. It’s different. I feel it’s not a totally explored area for me yet. I’d have to have a long time with somebody, and I haven’t.” She will. Today, she speaks enthusiastically of a relationship that started some time ago…

In the meantime, she performs her exquisite craft in her exquisite house and feels that life is OK. “I think basically that I still have the same problems that I always had, that if I really try to look at the reasons for my problems, the accident isn’t the main one. It might contribute, it might influence the way people look at me or the way I look at my life, but I don’t think I can blame my problems on that. Well, some of them I can—the fact that it takes me 15 minutes to get my socks on (laughs). But I don’t think things are really that much different.”

Tad Tanaka#

Tad’s a product of a first and second generation Japanese family, a high school education well suited to an agricultural life in his native San Joaquin Valley but to very little else, and an independent spirit. By the time he was 13, he was working part-time. By the time he finished high school, he left his family home in Fresno. As a final act of independence, he bought a motorcycle. And then he tangled with a car and broke his neck. C7. It was bad timing all around, because he’d just declared his independence in a fairly rebellious manner and now faced years of extreme dependence, and because the year was 1949, the town was Fresno, the available expertise was minimal and nobody around him was rich or particularly well connected. Tad was trapped.

And this is a 30 year escape saga.

If any object describes Tad Tanaka, it’s the well tended garden, about one foot by two feet, which sits on the kitchen table. It’s a monument to a fastidious nature. So is the mobile home he lives in. Every room is tiny, meticulously planned and very serviceable. No space remains unused and no space overflows. Most of us have taken pleasure, especially as children, in making small spaces fit our needs exactly. Tad’s trailer is a good fit; sculpted utility. The only large object he owns is a Buick Riviera, and the only things that have gotten out of his control are his books, which spill out onto all available surfaces. This is because he’s a compulsive reader and because he’s getting ready to move about 200 feet to a larger trailer. But not everybody who’s cramped for space admits to having 20 years of Scientific American hanging around…

We’re in Paramount, California, about an hour’s drive south of Los Angeles, talking about the way it was in 1949.

“I can’t say that I went through a rehabilitation experience at all. I think it should be remembered that things were pretty primitive all around. Education, rehabilitation, everything. When I compare the services available now with the services available then, there’s a huge difference. So I had no opportunity, really, to do anything. The automatic transmission was just coming out, right? That means you had to buy a new car if you were going to drive. Well I didn’t have that kind of money. And for that matter, I didn’t even know a quad could drive. There just weren’t the organizations to inform you about anything.”

Tad started in a Fresno hospital, and quickly developed a huge pressure sore. The hospital knew no more about the cure than the prevention, so he spent five months at Saint Mary’s in San Francisco patching up the damage the other hospital had inflicted in only six weeks.

Healed and forewarned, he returned to the Fresno hospital, then was discharged to his parents’ home. Since he had severe spasm, he gave the Fresno doctors an opportunity to experiment with some novel ideas. They kept him in bed, with leg braces on, for two years. The idea was “to stretch the spasm out.” After two years of unremitting spasm, he went back to San Francisco, had a tendon release, and his spasm was gone. Back to his parents’ home. Essentially, he spent the first three years after his accident in bed.

One good thing did happen at Saint Mary’s. “They put me in a five bed ward where they were all spinal injury, and that is where I started learning about other disabled people and how they lived. My attitude changed drastically —that wasn’t bad.”

But he kept coming home to Fresno. “I spent a lot of time trying to figure out what to do. Of course a lot of my time was just killing time, you know? I was looking into what kind of business I could operate from the home.” He was also reading a lot. His interests became much more intellectual, and he found himself drawn to the sciences and philosophy and eventually to psychology.

He developed a business selling stamps to stamp collectors, which brought him about $100 a month. But it looked like a dead end, something that would never fully support him. And he had these new interests emerging, and California, at that time, was coming in with their Aid to the Totally Disabled assistance, along with funds for attendant care. So he applied to DVR for schooling assistance. He was refused. They told him that he already was rehabilitated, he had a business going, and if he wanted to improve his situation he’d have to do it on his own. (It’s ironic that Tad is now a member of the State Rehabilitation Advisory Committee.)

He reviewed his options. Here in California, the land of gold plated personal injury liability settlements, Tad was awarded a magnificent $4,000, of which the lawyer took the top one thousand. In addition, the car’s driver was found guilty of negligence and fined $15. The state got that. So Tad took his $3,000 nest egg, augmented it with a scaled down version of his stamp business, bought a small second hand trailer, moved out of his parents’ house and enrolled at Fresno State in the spring of 1964. Without DVR. To keep it all straight, that’s 15 years after his accident.

At Fresno, he co-founded a local chapter of the National Paraplegia Foundation, his first step into advocacy. He also decided that Long Beach State better met his needs, so he moved, mobile home and all, to Southern California. By 1971, he had his degree in psychology. In 1972, he began a services program for disabled students at Long Beach. “Sort of by accident, my interests turned in that direction. And then I discovered an opening at Cypress College, I applied for that and I got it. So I’ve been working with disabled students ever since.” He helps students recruit attendants, find financial aid and work their way through the jungles of red tape surrounding all government services.

He’s also a rights activist. He’s a board member of the Dale Mackentosh Resource Center because it is located in Orange County and therefore serves his students. He’s a board member of the West Side (West Los Angeles) Community for Independent Living because that group is deeply involved in the effort to eliminate financial disincentives, a subject of particular concern to Tad. In 1976, he was one of the 16 elected delegates from California to the White House Conference on the Disabled. While in Washington, he dropped in on HEW to talk about welfare reform and made useful contacts with several legislators. He was back again in 1978, this time fighting disincentives. He has served the disabled very well.

Plans? He wants reduced advocacy activity, so he can read and recreate more. He’s moving to a two bedroom mobile home, not because he wants more space, but to ease the day when age might require him to have a live-in attendant. He thinks ahead a lot.

What has he learned during the last 30 years, other than that things have improved? That Regional SCI Centers and Independent Living Programs, with their wide range of services, are the best things that have happened to the disabled. That when in doubt, ask another disabled person; they’re the ones who know the most about solving problems and getting things done. That activity is life. “Especially in this area, there are so many things that a person can be active in, even a person who’s severely disabled. That’s the key: talk to other active people, get some ideas about what’s going on—there’s just hundreds and hundreds of things that you can get into. You can pick just about anything you want to.”

Don Scanlon#

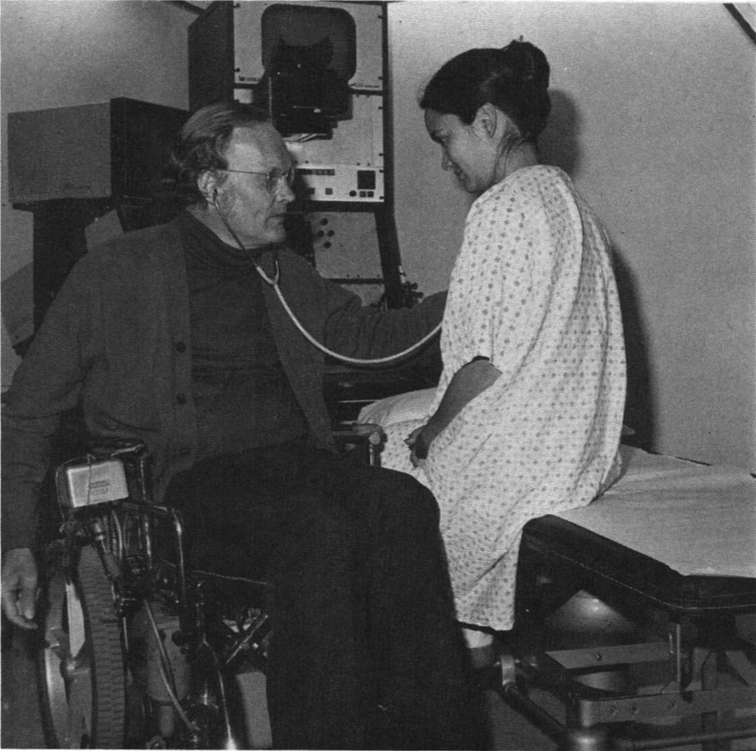

Doctor Don Scanlon has a wonderfully open, sensitive face, and a constant flow of humor that intermingles subtly with a lot of sincerity. He is bemused not depressed, when he speaks thus:

“I like to read. I’ve found myself, over the years, fascinated with books about prisoners. Solzhenitsyn and those things. And I used to think, God, I’m so fascinated with these things that I’m going to end up in prison some day. But I’m such a model citizen that I never could understand how the hell I would get into a prison, you know. So I thought, well, there’s nothing to that. Then one day after I’d been injured, I thought, Jesus Christ, look at what you’ve done. You’ve got yourself in your prison!”

Don not only got sent up for life; he got the electric chair. But not to worry —this is not a morbid tale. This is the happiest story of complete and rewarding rehabilitation I know.

In 1976, when Don was 46 years old, he had lived in Carmel for 15 years, was an internist in private practice and the Chief of Staff of the Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula. He had four daughters and a strong interest in the mountains and outdoor sports in general. While bicycling with his daughter he caught his front wheel between two boards on a small wooden bridge, went over the handlebars and torpedoed to the ground. I asked him how a doctor feels when diagnosing his own paralysis:

“There was a lot of denial. I was lying there on the ground and I was thinking —I wonder how long this is going to last? I’d like to get up and go on home. I knew that I’d broken my neck, but I really did not understand that this was QUADRIPLEGIA, and that this was what it was going to be from now on.”

He spent a month at his own hospital, then four months at Santa Clara Medical Center, one of the Regional SCI Units. While Don worked on his rehabilitation, his community worked on getting him back. The hospital, within days, had made personnel changes, found accessible office space, and created a new job for him. He also got a job offer from Santa Clara’s Rehabilitation Division (then run by Glenn Reynolds, a post-polio para). Making a living clearly wasn’t going to be a problem.

Don is now the Director of both the Cardiology and Medical Education departments of his old hospital. He has what he describes as a quarter-time private practice, with an office in town, but spends most of his working hours at the hospital. His office there is small and crowded, with a few minor design modifications for the wheelchair. There’s a panorama of Mount Everest and surrounding peaks, and it turned out we’d both been there before our accidents. I asked him how his professional life has been changed by the chair.

“I’d say it’s had remarkably little effect. For awhile there was the problem when I would see patients, with them feeling: Gee, I really can’t tell you my problems, Doc, and your problems are so much greater than mine that mine are nothing. That created a little bit of a barrier to communication for awhile. On the other hand, in some instances, it’s given me a tremendous entrée. I can go into a room of somebody who’s had an injury like this, people who’ve had strokes or something, and immediately talk with them. And they know that I know pretty well what they’re going through.”

Does he feel any limitations as a doctor? Not many. As a C5,6, his hands aren’t sensitive enough for some aspects of physical examinations. He doesn’t make house calls very often, but he has made a few. He has recovered enough thumb movement in one hand to hold a fork or spoon or write without a splint. “I just put the pen down between these two fingers, and I can write pretty well. You know, a doctor doesn’t have to write too well; he’s got a reputation to uphold. I write better than most of my colleagues.” And with an infectious grin, he reports his ability to slip his hand down over the neck of a wine bottle and drink from it, a matter of real importance.

He clearly feels comfortable with his own competence, but what about medicine as a schooling objective? “I’ve thought about a young person wanting to go through medical school as a quad. I wouldn’t say it can’t be done. Probably it has been or will be done, but I must say I’m glad I don’t have to do that.” Nevertheless, he does know of cord-injured psychologists, radiologists and psychiatrists who have received their training post-injury. And there’s the dermatologist in Santa Cruz who works from an iron lung…

About new injuries: “A person takes into SCI whatever he already is as a person. If he’s sour on the world, he’s gonna have a hell of a time. I don’t exactly know what that person needs to do, or I can’t tell him what to do, other than to somehow accept what he’s got and realize that this is just one more problem of life. It’s of a different sort, but I don’t even think it’s worse, in a way, than the problems that everybody else has to face. We always manage to bring our problems up to the level which is the most we can stand. If you don’t have enough problems, if there aren’t enough problems provided in your life for you by the way things are going, you’ll create them just up to however much you can take. Right up to the brim. Spinal cord injury, that just relieves you of the responsibility of providing those problems.”

How about SCI and aging? “I think, look at what I’ve gone through already, and it’s worked out some way or another. And it will when I get older too. No, I don’t worry about what’ll happen when I get old.”

And about his prison: “I just don’t feel imprisoned anymore. Something’s happened, and I don’t feel that way anymore. My life has expanded; it’s wonderful. I really live a full life, a good life, a rewarding life, a fulfilled life. Neat things are happening to me all the time. They have been especially ever since this injury. I’ve never seen or experienced such an outpouring of love from the people in my community. It’s magnificent. That’s not to say there are no problems, but it is to say that in the presence of those problems, life is, for me, better than it ever has been.”

I hear a lot of hype from wheelers who exude cavalier statements about how SCI has improved their lives, and generally disregard it. Don Scanlon’s not saying that his injury improved his life, but that he improved his life while simultaneously coping with a potentially devastating injury. That’s very different and very real. It’s a wonderful thing to see. I don’t inspire easily, and I’m unabashedly inspired.

Bob Bowen#

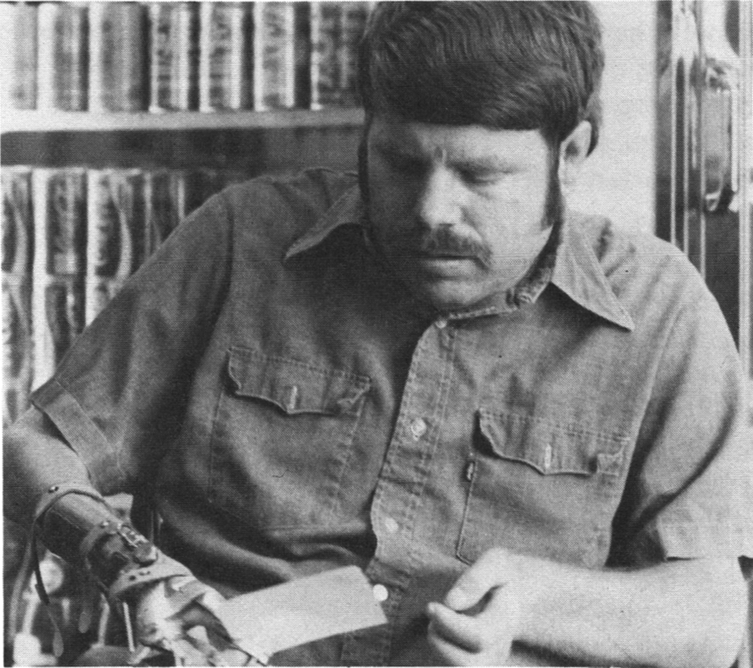

In 1963, Bob Bowen had just finished high school, was working on his father’s ranch in Missouri, and was looking forward to being big in the sports scene at Texas Tech the next fall. He’d already been accepted for admission. He was breaking a horse for his sister when he was thrown, which gave him a C6,7 fracture. This however, is not the hard luck part of the story.

Bob’s injury was incomplete, and he was soon getting around well on crutches and short leg braces. He got in several semesters at Texas Tech, worked at times on the ranch, got married and was doing fine when his family traded for a new ranch near Chadron, Nebraska.

It was in 1970 that Bob’s luck turned sour. His paralysis started getting worse, and nobody knew why. For someone with an acute awareness of the consequences, progressively advancing paralysis must have been a demonic bummer. He had two traumatic and unsuccessful operations to halt the paralysis before he went to Craig. A neurosurgeon found a large cyst formed on his spinal cord, drained it, and successfully stabilized his condition. But by that time, he was a complete quadriplegic. This was pretty disheartening — so much so that it broke up his marriage. “We were both scared, my wife and I, and neither one of us was willing to put out what the other needed at the time.” So with no wife, no job and very little physical function, Bob had to make adjustments that made his original accident seem trivial.

“It’s a case of, here you’re sliding downhill, and you almost have to hit bottom. Then something kind of wakes you up and shakes you and says, Well, what are you gonna do? It can’t get any worse. You gotta start building from here. You finally gotta someday wake up and realize that you’re goin’ to hell and if you don’t straighten your act up, you’re never gonna do nothin’. So you just start from there and go.

“Getting out … it’s hard to re-establish yourself. You almost have to start over from scratch. You’ve really got to make up your mind that you want to make it.”

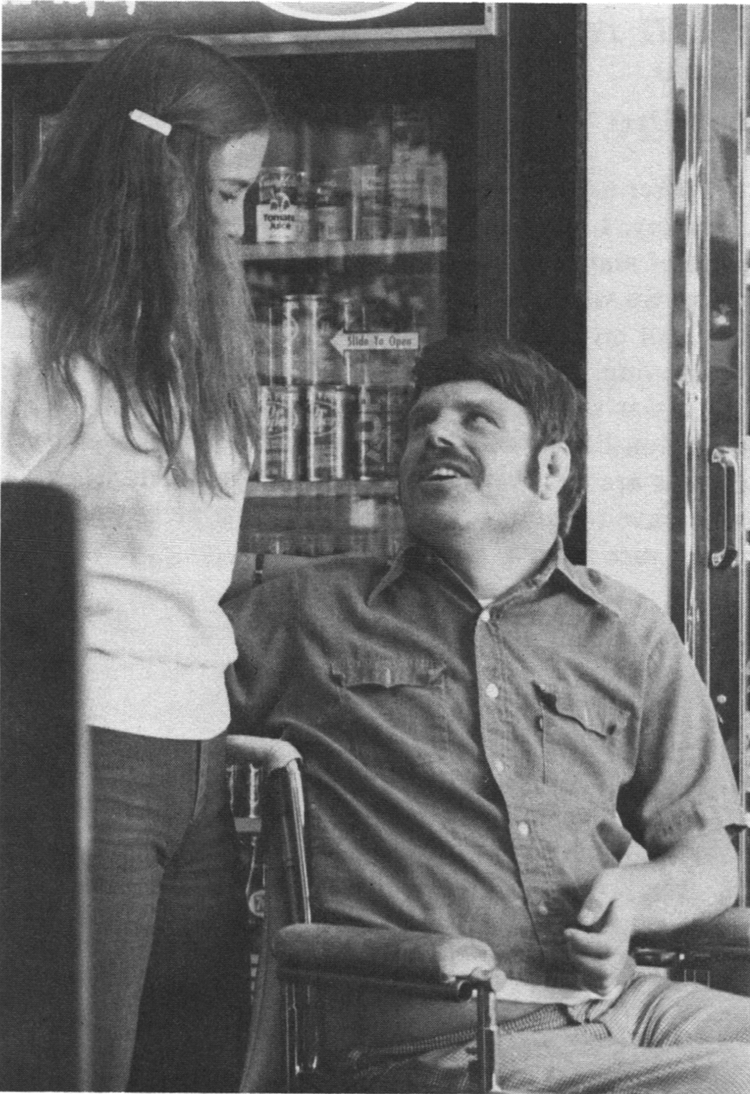

He decided he wanted to make it, then he figured out how: “Finding jobs is difficult, especially in a small town like Chadron. And I just decided that if I was gonna get on my own and be able to work and make a living, I was gonna have to create my own job. So I bought the liquor store and became my own boss, and it worked out well for me. I’ve found that I can compete in the business world, and the chair doesn’t make any difference at all.”

The store has done well and so has Bob. As we talked in his house, friends dropped by to chat or invite him out. Employees in the store have a close rapport with him, and he’s obviously well liked in his community. Part of this ease of communication must come from the fact that he has never felt adverse public attitudes directed at him—earlier, on crutches and braces, and now, in electric chair and hand splint. He doesn’t worry about how he appears to other people. They can worry up a storm if they want to, but that’s their problem.

What other businesses could a motivated gimp get into?

“I really don’t think you’re limited. Naturally, you can’t get into something that gets into a lot of physical labor. But here in Chadron, I could manage the Gamble’s store or run a filling station. I could go operate one of those three or four hundred cow ranches, if need be. It kind of depends on what your background is and what you like to do. If you like to do it, you’re not limited.”

Bob obviously doesn’t feel limited. He’s sold his liquor store, bought a house, and plans to finish his business degree. After that, he’s thinking maybe he’ll get a real estate license or go on for a master’s degree in finance so that he can become a stockbroker. In the meantime, he’ll support himself with the proceeds from the sale of the liquor store and a small gun business which he’ll run from his home. (He used to own a gun store, and still holds a federal firearms license. He sends out a gun catalog which is imprinted with his name. This allows customers to order through him, using his license in effect, without requiring him to handle merchandise directly.) And if none of these things should appeal when the time comes, Bob’s got a head full of alternatives he’s confident will work.

Personal relationships? He feels they’ve become deeper: “It seems it works out better. You’re more sincere about each other. I’ve had a lot of beautiful relationships since I’ve been in this chair.”

He also has no problem with attendants, although he doesn’t like the word because he feels it’s demeaning. He gives college or local working kids room, board and utilities, but no pay. Bob tends to think of his present attendant as a brother, and it’s the mutual respect that makes it work. He’s never had trouble finding good people.

I suspect that it is Bob’s respect for and openness to all ideas and all people which makes his life seem to work so smoothly. And he’s a winner, of course, because that’s what he decided to be.

Brian McCarthy#

Presents A Day on the Bay

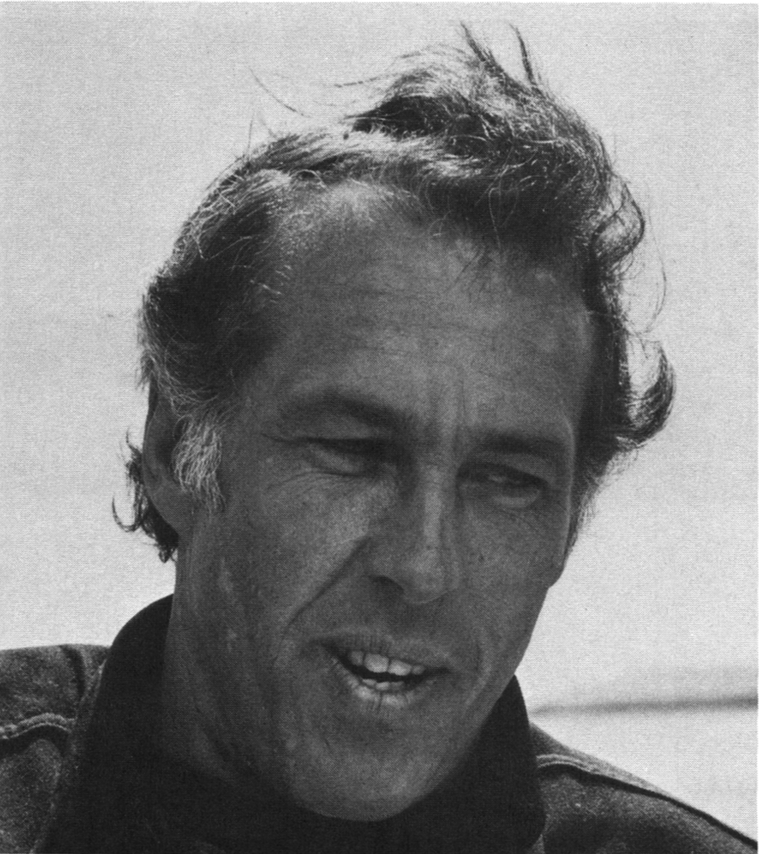

After a month on the road interviewing wheelers every day, I was tired of work, tired of extracting histories and wisdom from people, maybe even tired of gimps. So when Brian invited two friends and me to go for a sail on San Francisco Bay, I was eager to spend a day playing. Brian, of course, is a para.

It was such a supremely normal day of sunny recreation that I include excerpts just to show that days like this are out there for whoever wants them. They don’t have to happen on a sailboat. Just pick nice places, nice people, and loaf resolutely.

Did you sail before your accident? “Yeah, so this was something very easy to ease into after the accident. And sailing’s a pretty easy sport. I mean, if you and I can get the boat set up and go sailing, you know it can’t be too difficult.”

Tell me about the boat. “It’s a little 22-foot Santana sloop, weighs 3,000 pounds, fiberglass. A couple of sails, a mast, all kinds of strings. Usual garden-variety stuff.” Done any racing? “Oh, a little bit in the Bay. Maybe about 10, 12 races a year. Local races, nothing fancy.” Ever win? “Occasionally. When I have a good crew.”

Why do you use braces? “Mainly to keep from falling off the boat.” That makes sense. “You extend them so you don’t slide off when you’re heading downhill.” I can’t even see that you’ve got braces on. “They’re those new fiberglass ones. You can even change shoes. That’s not a big deal to most people, but it’s a big deal to us. You can change your shoes without taking your braces off.”

Could I operate a sailboat like this without braces? “It’d be a lot easier with leg braces, it really would. Because when it gets windy, you have trouble hanging on. We can get out in the windy part and watch you hang on. That’ll be the laugh of the day. Your arms get tired. It’s much easier to let the braces do the work for you.”

How’d you have your accident? “Rolled a jeep, June of 64. I was 26.” I thought you were a stockbroker then. How do you roll a jeep in the stock market? “I was a stockbroker. It was the army. It was that two-week summer training thing, you know, that we all had to do in those days. We hadn’t thought about going to Canada yet, so went to summer camp instead.”

Then you became a CPA? “I was in the stock market for a couple of years before my accident and about eight years after. Then I went back to school for a couple of years, which was really fun, getting back in touch with the kids again and just taking it easy for awhile.” How’s business? “Right now, it’s very small. That’s why we’re sailing on Friday in the middle of the tax season. It’ll grow. (Becomes tour guide.) This is historic Port Richmond now. This is serious stuff. We’re gonna come about. (Comes about.) How’s that? Look like the America’s Cup, huh? We didn’t even hit anything. You want to steer? (Moves into the cockpit, stands comfortably on bunks.) Don’t bump into that piling over there, or any of the large land masses around.”

At the end of the day, Brian took the helm and expertly returned us to the dock. His slip was easy to spot because of the two wheelchairs glinting in the afternoon sun. Nobody had missed them. Wheelchairs are the hot tip for most SCI’s, but it’s nice to leave them behind now and then. You don’t need a chair to loaf.

Mary Wilson#

“Recreation typifies fun, and that’s the bottom line in all this anyway. I mean, we can get as therapeutic as we want, but if you can’t have fun, what good’s your life going to be? You have to be able to feel that kind of happiness again.”

Mary is a raven-haired beauty, appears indecently healthy and looks as if happiness is a large part of her life. At lunch in a Sausalito restaurant, she interacts with others with a nice sense of authority. She projects herself with such confidence that no gimp/AB interface exists. What I guess that means is that she has a lot of poise.

Now we’re back in her nearby apartment, which is a cathouse (well, there are a lot of cats around), talking about recreation and SCI. Mary insists that she’s not a recreational therapist. Her schooling is in marketing. So she’s a Recreationalist or Therapeutic Activities Leader or whatever you choose to call her.

Mary got into whatever it is she does, of course, by breaking her back. “I made the mistake of falling out of a car. It was stupid, but you live ’n learn!” L1,2. 1973. Twenty-three years old. Rehab at Kaiser, in Vallejo.

She found an apartment, totally unsuitable, and then took an interviewing job in the financial district of San Francisco. “I spent my entire salary on taxicabs, going downtown, but it was good. It was maybe the turning point in my rehabilitation. It saved me, being busy.” The job convinced her that activity was the key to her survival. Her world tended to stop when her activities stopped.

A year after her accident, it was time for a hospital re-evaluation. “I was king of the mountain. Here I am, a veteran crip. It really gave me a whole different sense of myself. I felt extremely useful and valuable, that my experience was worth something.” She was offered a job as an aide to the recreational therapy specialist, took it, and trained and worked for six months as a Recreational Whatchamacallit. At that point, an administrative problem closed down the rehab center, and she was out on the streets again. She turned to The Berkeley CIL.

At CIL: “I was overwhelmed initially. My focus up til then had been new SCI’s, and I pretty much thought that all people in wheelchairs were of that nature. And to see all these active, integrated quads —I was really humbled. I almost felt guilty being a new para. But I went out and bought a whole bunch of flannel shirts and dug out all my old jeans, and before I knew it, I was there.”

Since I’d just visited the Berkeley CIL, I wanted to know what Mary thought of it: “I have a lot of belief in what a group organization can accomplish, and what they, in particular, have accomplished. Legislatively, they’ve done wonders for us. As a role model, they’ve done wonders. If you’re looking at it from the outside, it’s great, and that’s a good purpose they’re serving. When you’re living within those confines, it’s a different story. I see it as a haven, a sheltered environment and a real hideout. I know a number of people who cannot survive outside of that. Then you’re losing what, hopefully, you were trying to accomplish.”

Mary put her flannel shirts aside, finally, and went back to work as a Whatchamacallit, this time at the Ralph K. Davies Medical Center in San Francisco. Whatever her job description was, it involved recreation.

She feels that sports and recreation are far and away the easiest way to educate the public on disability. “People have a tendency to believe that life pretty much stops upon injury. Things do go on, and seeing people out and active and smiling, no less, is always an education to the average person. So we’re using that as a way of getting our community accessible and educated, our programs funded. It’s serving many purposes that have not a whole lot to do with sports.”

And the sports themselves? “I think the sports circuit itself is great because it helps build self-esteem, because you’re developing your physical powers and your coordination and mobility. You’re used to being looked at. You’re under focus. You’re traveling, you’re meeting lots of people —it has a lot of really healthy side effects. I mean, I’ve never seen such a smorgasbord of healthy people in my life as I have at the National Wheelchair Games.

“With the young people that are on our team, it’s doing amazing things. Positive, healthy things. When you’re growing up, sports play a big part of your development, so it’s giving them an opportunity to develop in similar areas. For the older people on our team, it helps keep them down to earth. They don’t get too consumed in their professions. It keeps you rounded.”

How about the much older people? “I think it keeps them from getting locked into little groups where they become isolated. It keeps them in the flow of things. I don’t see any kind of age discrimination going on amongst the competitors.”

I wanted to know what high SCI’s can do for recreation: “Not very much until they come down. Oh, you mean high level injuries. One fellow, who got involved in the program last year, is a C4 quad. He does have some arm movement — enough to push a chair — which is the criterion for getting into wheelchair sports competitively. After his first season of running with us, he was incredibly enlightened to the fact that he had some physical powers, that somebody gave him some involvement on a physical level. Prior to that, I think everybody had been saying, Well, John, Go to school. Get a degree. Develop your mental powers. He felt that that was his only option for involvement in society.” In this case, sports got him into traveling so much, worldwide, that he is now going to a travel agents’ school so that he can open a travel agency. In Thailand.

It’s not all sports. Mary speaks of a Cl quad on a respirator, an artist before his injury. He got back into painting, using a mouthstick, and is now opening a cafe/coffee house/ gallery to showcase his work. “That’s pretty amazing, a Cl quad not just integrating into the community but running his own business. And his big thing is mingling, socializing, showing people his art work; and that’s an active stance.”

For most new high level injuries, Mary feels that recreation is partly a matter of getting out in the community a lot, regaining confidence in the world, going to theatres, parks and restaurants. “Anybody can develop game skills, or the low key diversionary activities, but it takes exposure and a little bit of technique to learn how to handle yourself out on the streets again.”

While Mary’s getting new injuries back on the streets, she’s getting herself out on the Marin County jogging paths, working on long distance pushing. She likes the reactions she gets from passersby: “They’re positive, friendly, accepting reactions. Everybody’s sort of delighted that we all have some sort of similar mobility now, whether it’s on a skateboard or roller skates or a bicycle. All different forms of wheels out there. They all want to know, Why are the wheels tilted, Why is the chair this or that? That’s neat! Let’s see you do a wheelie.”

Other plans: Mary wants to model and/or act in commercials and films. She sees no reason why someone in a wheelchair couldn’t present the product just as effectively as a normie, and she’d like to be the one to break that ice. I tried to call her recently, and found that she’s no longer at Ralph K. Davies. Maybe she’s out having a Pepsi Day. Maybe she’s racing through airports, blowing Pepsodent kisses, squeezing the Charmin, or just having fun.

Parting shot: “Sometimes it’s hard to have fun or sometimes it’s hard to laugh after you go through some of the experiences that we have all shared. But there are ways of finding that kind of joy and happiness again. It keeps coming to mind, that old song, I Ain’t Never Had Too Much Fun. And that’s real true.”